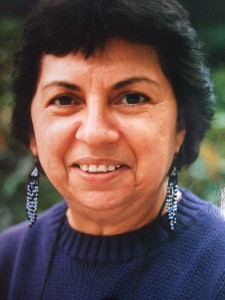

Biography

Born in 1942 in the Rio Grande Valley of south Texas to sixth-generation Mexicanos, this self-described “Chicana, Tejana, working-class, dyke-feminist poet, writer-theorist” was punished in grade school for her inability to speak English “properly,” yet is now recognized as a leading cultural theorist and a highly innovative writer (see Language). Her work, which is often cited by scholars in a wide variety of fields, has challenged and expanded previous views on cultural studies, ethnic identities, feminism, composition, queer theory, and U.S. American literature. As one of the first openly lesbian Chicana writers, Anzaldúa has played a major role in redefining lesbian and Chicano/a identities. And as co-editor of This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, a ground-breaking collection of essays and poems widely recognized as the premiere multicultural feminist text, she played an equally vital role in developing an inclusionary feminist movement. Gloria Anzaldúa passed away in 2004.

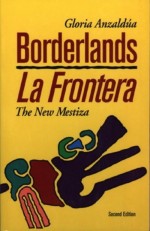

Anzaldúa’s published works include This Bridge Called My Back; Borderlands/LaFrontera: The New Mestiza (1987), a hybrid collection of prose, poetry, memoir, history, social protest, and revisionist myth; Making Face, Making Soul/Haciendo Caras: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Women of Color (1990), a collection used in many university classrooms throughout the country; and two children’s bilingual books – Friends from the Other Side/Amigos del otro lado and Prietita and the Ghost Woman/ Prietitay la Llorona. Her projects have included Interviews/Entrevistas, a collection of interviews; a collection of short stories; a novel-in-stories; a writing manual; a book of daily meditations; a young-adult novel; and and the edited collection This Bridge Called My Back, Twenty Years Later. Anzaldúa has won numerous awards, including the Before Columbus Foundation American Book Award, the Lamda Lesbian Small Book Press Award, an NEA Fiction Award, and the Sappho Award of Distinction (see also Gender and Nation, Third World and Third World Women).

Brief Analysis of Writings

Throughout her work Anzaldúa explores a diverse set of issues, including (but not limited to) the destructive effects of externally imposed labels and the interlocking systems of oppression that marginalize people who – because of their class, color, gender, language, and/or sexuality – do not belong to dominant cultural groups: Chicana/o identities; lesbian sexualities; butch/femme roles; bisexuality; altered states of reality; transformational identity politics; and homophobia and sexism, within both the dominant US culture and Mexican-American communities.

Although Borderlands/La Frontera defies easy classification, it can perhaps be described as cultural autobiography. In this hybrid collection of poetry and prose, Anzaldúa transgresses conventional literary genres and blends personal experience with history and social protest with poetry and myth to construct self-affirmative individual and collective identities. Even her linguistic style, or “code switching,” – her transitions from standard to working-class English to Chicano Spanish to Tex-Mex to Nahuatl-Aztec – furthers this attempt to integrate personal and communal self-definition. Interweaving accounts of the racism, sexism, and classism she experienced growing up in south Texas with historical and mythic analyses of the successive Aztec and Spanish conquests of indigenous gynecentric Indian tribes, Anzaldúa simultaneously reclaims her political, cultural, and spiritual Mexican/Nahuatl roots and constructs a mestizaje identity, a new concept of personhood that synergystically combines apparently contradictory Euro-American and indigenous traditions (see Mimicry, Ambivalence, Hybridity, Hybridity and Postcolonial Music).

Borderlands/La Frontera has played a formative role in the ways contemporary scholars think about border issues, the concept of the borderlands, ethnic/gender/sexual identities, and conventional literary forms. Anzaldúa extends the previous views of the borderlands as a distinct geographical location to encompass psychic, sexual, and spiritual borderlands as well (see Benedict Anderson). Her concept of the new mestiza has been equally influential, for it goes beyond biological identity categories to incorporate other forms of identity as well. For Anzaldúa, new mestizas are people who inhabit multiple worlds because of their gender, sexuality, color, class, personality, spiritual beliefs, or other life experiences. Borderlands/La Frontera and in her other writings, Anzaldúa redefines twentieth-century definitions of lesbian identity. She rejects the ethnocentrism implied by the words “lesbian” and “homosexual” and adopts culturally-specific terms like “mita’y mita’” (“half and half”) to describe her sexual preference. As she acknowledges these terms’ derogatory implications, she simultaneously challenges conventional Eurocentric sexual and gender categories and exposes Mexican Americans’ heterosexism, homophobia, and sexism. Associating physical desire with her desire to reclaim her cultural roots, Anzaldúa expands conventional western notions of lesbian identity in three ways. First, by identifying her sexuality with non-Western cultural traditions, she counters the commonly held Chicano belief that same-sex desire indicates ethnic betrayal or assimilation into the dominant Anglo culture. Second, her simultaneous focus on sexuality and ethnicity complicates conventional Eurocentric descriptions of lesbian identity formation, thus providing an important corrective to the monolithic images of lesbian identity found in much twentieth-century Euro-American lesbian literature. And finally, this dual focus on sexual and ethnic identities underscores Anzaldúa’s ability to make complex negotiations between two or more apparently disparate communities.

Anzaldúa’s Making Face, Making Soul/Haciendo Caras indicates a further extension of this desire to create alliances and dialogues among diverse peoples. In this 1990 anthology of creative and theoretical pieces by self-identified women of color, Anzaldúa attempts to develop coalitions between nonacademic and academic social activists. In the preface, she rejects the inaccessible, elitist nature of academic “high” theory and underscores the importance of inventing new theorizing methods, “mestizaje” theories, that create new categories for those of us left out or pushed out of the existing ones.

It is this ability to create expansive new categories that makes Anzaldúa’s work so vital to twentieth-century social actors, thinkers, and scholars. Destabilizing apparently fixed classifications and provocatively crossing sexual, cultural, gender, and genre boundaries, her writing breaks down the categories that lead to stereotyping, over-generalizations, and arbitrary divisions among apparently dissimilar groups. In so doing, Anzaldúa opens up new spaces where mestizaje connections – alliances between people from diverse sexualities, cultures, genders, and classes – can occur (see also Leslie Marmon Silko, Isabel Allende, Julia Alvarez, Magical Realism, Pablo Neruda, Mario Vargas Llosa).

Works by Anzaldúa

- Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Spinsters/AuntLute, 1987.

- —. “Bridge, Drawbridge, Sandbar or Island: Lesbians-of-Color Hacienda Alianzas.” Ed. Lisa Albrecht and Rose M. Brewer. Bridges of Power: Women’s Multicultural Alliances. Philadelphia: New Society, 1990. 216-31.

- —. “En rapport, In Opposition: Cobrando cuentas a las nuestras.” Making Face, Making Soul/Haciendo Caras: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Women of Color. Ed. Gloria Anzaldúa. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Foundation, 1990. 142-48.

- —. Friends from the Other Side/Amigos del Otro Lado. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press, 1993.

- —. Haciendo Caras/Making Face, Making Soul: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Women of Color. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Foundation, 1990. (Edited)

- —. “La Prieta.” This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. Ed. Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa. New York: Kitchen Table, Women of Color Press, 1983. 198-209.

- —. “Metaphors in the Tradition of the Shaman.” In Conversant Essays: Contemporary Poets on Poetry. Ed. James McCorkle. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1990. 99-100.

- —. Pietita and the Ghost Woman/Prietita y La Llorona. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press, 1995.

- —. “She Ate Horses.” Lesbian Philosophies and Cultures. Ed. Jeffner Allen. New York: State University of New York Press, 1990. 371-88.

- —. “Speaking in Tongues: A Letter to Third World Women Writers.” This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. Ed. Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa. New York: Kitchen Table, Women of Color Press, 1983. 165-74.

- —. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. New York: Kitchen Table, Women of Color Press, 1983. (Co-edited with Cherríe Moraga)

- —. “To(o) Queer the Writer – Loca, escritora y chicana.” Inversions: Writing by Dykes, Queers, and Lesbians. Ed. Betsy Warland. Vancouver: Press Gang, 1991. 249-64.

Selected Writings About Anzaldúa

- Adams, Kate. “North american Silences: History, Identity, and Witness in the Poetry of Gloria Anzaldúa, Cherríe Moraga, and Leslie Marmon Silko.” Ed. Elaine Hedges and Shirley Fisher Fishkin. Listening to Silences: New Essays in Feminist Criticism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.130-45.

- Alarc, Norma. “Chicana Feminism: In the Tracks of “The” Native Woman.” Living Chicana Theory. Ed. Carla Trujillo. Berkeley: Third Woman Press, 1998. 371-82.

- Barnard, Ian. “Gloria Anzaldúa Queer Mestisaje.” MELUS 22(1997): 35-53.

- Emberly, Marcus. “Cholo Angels in Guadalajara: The Politics and Poetics of Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera. Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 8 (1996): 87-108.

- Fowlkes, Diane L. “Moving from Feminist Identity Politics to Coalition Politics through a Feminist Materialist Standpoint of Inter-subjectivity in Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Hypatia12 (1997): 105-24.

- Franklin, Cynthia G. Writing Women’s Communities: The Politics and Poetics of Contemporary Multi-Genre Anthologies. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997.

- Keating, Ann Louise. “(De)Centering the Margins? Identity Politics and Tactical (Re)Naming.” Other Sisterhoods: Women Writers of Color and Literary Theory. Ed. Sandra Kumamoto Stanley. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998. 23-43.

- —. “Myth Smashing, Myth Making: (Re)Visionary Techniques in the Works of Paula Gunn Allen, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Audre Lorde.” Journal of Homosexuality 26 (1993): 73-95.

- —. “Transcendentalism Then and Now: Towards a Dialogic Theory and Praxis of Multicultural US Literature.” Rethinking American Literature. Eds. Lil Brannon and Brenda Greene. Urbana: National Council of Teachers of English, 1997. 50-68.

- —. Women Reading Women Writing: Self-Invention in Paula Gunn Allen, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Audre Lorde. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996.

- —. “Writing, Politics, and las Lesberadas: Platicando con Gloria Anzaldúa.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 14 (1993): 105-30.

- McRuer, Robert. The Queer Renaissance: Contemporary American Literature and the Reinvention of Lesbian and Gay Identities. New York: New York University Press,1997.

- Saldvar., José David. The Dialectics of Our America: Genealogy, Cultural Critique, and Literary History. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991.

- Sandoval, Chela. “U.S. Third World Feminism: The Theory and Method of Oppositional Consciousness in the Postmodern World.” Genders 10 (Spring 1991): 1-25.

- Yarbro-Bejarano, Yvonne. “Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/Lafrontera: Cultural Studies, “Difference,” and the Non-Unitary Subject.” Cultural Critique 28 (1994): 5-28.

- Zita, Jacquelyn N. “Anzaldúan Body.” Body Talk: Philosophical Reflections on Sex and Gender. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998. 165-83.

Author: Ana Louise Keating, 1999

Last edited: October 2017