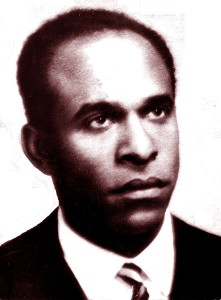

Biography

Frantz Fanon’s relatively short life yielded two potent and influential statements of anti-colonial revolutionary thought, Black Skin, White Masks (1952) and The Wretched of the Earth (1961). These works have made Fanon one of the most prominent contributors to the field of postcolonial studies.

Fanon was born in 1925, to a middle-class family in the French colony of Martinique. He left Martinique in 1943, when he volunteered to fight with the Free French in World War II, and he remained in France after the war to study medicine and psychiatry on scholarship in Lyon. Here he began writing political essays and plays, and he married a Frenchwoman, Jose Duble. Before he left France, Fanon had already published his first analysis of the effects of racism and colonization, Black Skin, White Masks (BSWM), originally titled “An Essay for the Disalienation of Blacks,” in part based on his lectures and experiences in Lyon (see Representation, Essentialism, Anglophilia).

BSWM is part manifesto, part analysis; it both presents Fanon’s personal experience as a black intellectual in a whitened world and elaborates the ways in which the colonizer/colonized relationship is normalized as psychology. Because of his schooling and cultural background, the young Fanon conceived of himself as French, and the disorientation he felt after his initial encounter with French racism decisively shaped his psychological theories about culture. Fanon inflects his medical and psychological practice with the understanding that racism generates harmful psychological constructs that both blind the black man to his subjection to a universalized white norm and alienate his consciousness. A racist culture prohibits psychological health in the black man.

For Fanon, being colonized by a language has larger implications for one’s consciousness: “To speak … means above all to assume a culture, to support the weight of a civilization” (17-18). Speaking French means that one accepts, or is coerced into accepting, the collective consciousness of the French, which identifies blackness with evil and sin. In an attempt to escape the association of blackness with evil, the black man dons a white mask, or thinks of himself as a universal subject equally participating in a society that advocates an equality supposedly abstracted from personal appearance. Cultural values are internalized, or “epidermalized” into consciousness, creating a fundamental disjuncture between the black man’s consciousness and his body. Under these conditions, the black man is necessarily alienated from himself (see Colonial Education).

Fanon insists, however, that the category “white” depends for its stability on its negation, “black.” Neither exists without the other, and both come into being at the moment of imperial conquest (see Orientalism). Thus, Fanon locates the historical point at which certain psychological formations became possible, and he provides an important analysis of how historically-bound cultural systems, such as the Orientalist discourse Edward Said describes, can perpetuate themselves as psychology. While Fanon charts the psychological oppression of black men, his book should not be taken as an accurate portrait of the oppression of black women under similar conditions. The work of feminists in postcolonial studies undercuts Fanon’s simplistic and unsympathetic portrait of the black woman’s complicity in colonization (see Spivak, Gender and Nation, Chicana Feminism, Third World and Third World Women, Angela Davis).

In 1953, Fanon became head of the psychiatry department at the Blida-Joinville Hospital in Algeria, where he instituted reform in patient care and desegregated the wards. During his tenure in Blida, the war for Algerian independence broke out, and Fanon was horrified by the stories of torture his patients — both French torturers and Algerian torture victims — told him. The Algerian War consolidated Fanon’s alienation from the French imperial viewpoint, and in 1956 he formally resigned his post with the French government to work for the Algerian cause. His letter of resignation encapsulates his theory of the psychology of colonial domination, and pronounces the colonial mission incompatible with ethical psychiatric practice: “If psychiatry is the medical technique that aims to enable man no longer to be a stranger to his environment, I owe it to myself to affirm that the Arab, permanently an alien in his own country, lives in a state of absolute depersonalization … The events in Algeria are the logical consequence of an abortive attempt to decerebralize a people” (Toward the African Revolution 53) (see Geography and Empire, Maps in Colonialism).

Following his resignation, Fanon fled to Tunisia and began working openly with the Algerian independence movement. In addition to seeing patients, Fanon wrote about the movement for a number of publications, including Sartre’s Les Temps Modernes, Presence Africaine, and the FLN newspaper el Moudjahid; some of his work from this period was collected posthumously as Toward the African Revolution (1964). But Fanon’s work for Algerian independence was not confined to writing. During his tenure as Ambassador to Ghana for the Provisional Algerian Government, he worked to establish a southern supply route for the Algerian army.

While in Ghana, Fanon developed leukemia, and though encouraged by friends to rest, he refused. He completed his final and most fiery indictment of the colonial condition, The Wretched of the Earth, in 10 months, and the book was published by Jean-Paul Sartre in the year of his death. Fanon died at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, where he had sought treatment for his cancer, on December 6, 1961. At his request, his body was returned to Algeria and buried with honors by the Algerian National Army of Liberation.

In The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon develops the Manichean perspective implicit in BSWM. To overcome the binary system in which black is bad and white is good, Fanon argues that an entirely new world must come into being. This utopian desire, to be absolutely free of the past, requires total revolution, “absolute violence” (37). Violence purifies, destroying not only the category of white, but that of black too. According to Fanon, true revolution in Africa can only come from the peasants, or “fellaheen.” Putting peasants at the vanguard of the revolution reveals the influence of the FLN, who based their operations in the countryside, on Fanon’s thinking. Furthermore, this emphasis on the rural underclass highlights Fanon’s disgust with the greed and politicking of the comprador bourgeoisie in new African nations (see also Hegemony in Gramsci). The brand of nationalism espoused by these classes, and even by the urban proletariat, is insufficient for total revolution because such classes benefit from the economic structures of imperialism. Fanon claims that non-agrarian revolutions end when urban classes consolidate their own power, without remaking the entire system. In his faith in the African peasantry as well as his emphasis on language, Fanon anticipates the work of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who finds revolutionary artistic power among the peasants.

Given Fanon’s importance to postcolonial studies, the obituaries marking his death were small; the two inches of type offered by The New York Times and Le Monde inadequately describe his achievements and role. He has been influential in both leftist and anti-racist political movements, and all of his works were translated into English in the decade following his death. His work stands as an important influence on current postcolonial theorists, notably Homi Bhabha and Edward Said (see Mimicry, Ambivalence and Hybridity, and Orientalism).

British director Isaac Julien’s Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask was released by California Newsreel in 1996. Weaving together interviews with family members and friends, documentary footage, readings from Fanon’s work, and dramatizations of crucial moments in his life, the film reveals not just the facts of Fanon’s brief and remarkably eventful life but his long and tortuous journey as well. In the course of the film, critics Stuart Hall and Françoise Verges position Fanon’s work in his own time and draw out its implications for our own.

Works by Frantz Fanon

- Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove, 1967. Reprint of Peau noire, masques blancs. Paris: Points, 1952.

- Studies in a Dying Colonialism, or A Dying Colonialism. New York: Grove, 1965. Reprint of L’an cinq de la revolution algerienne. Paris: F. Maspero, 1959.

- Toward the African Revolution. New York: Grove, 1967. Reprint of Pour la revolution africaine. Paris, 1964.

- The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove, 1965. Reprint of Les damnes de la terre. Paris, 1961.

Selected Criticism

- Abel, Lionel. “Seven Heroes of the New Left.” The New York Times Magazine. 5 may 1968.

- Bhabha, Homi. “Interrogating Identity: Frantz Fanon and the Postcolonial Prerogative.” The Location of Culture. London: Routledge, 1994. 40-66.

- de Beauvoir, Simone. Force of Circumstance. New York: Putnam,1964.

- Bergner, Gwen. “Who Is That Masked Woman? or, The Role of Gender in Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks.” PMLA 110.1 (January 1995): 75-88.

- Caute, David. Frantz Fanon. New York: The Viking Press, 1970.

- Fuss, Diana. “Interior Colonies: Frantz Fanon and the Politics of Identification.” Diacritics (Summer-Fall 1994): 20-42.

- Gates, Henry Louis. “Critical Fanonism.” Critical Inquiry 17(1992): 457-470.

- Geismar, Peter. Fanon. New York: The Dial Press, 1971.

- Gendzier, Irene L. Frantz Fanon: A Critical Study. New York: Pantheon Books – Random House, 1973.

- Gordon, Lewis R. Fanon and the Crisis of European Man. New York: Routledge, 1995.

- “Homage to Frantz Fanon.” Presence Africaine 12 (1962): 130-152. Ten writers, politicians and scholars contributed to this special section, including Aime Césaire and Nkrumah.

- Memmi, Albert. “The Impossible Life of Frantz Fanon.” Massachusetts Review (Winter 1973): 9-39.

- Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Vintage Books – Random House, 1993.

- Seigel, J. E. “On Frantz Fanon.” American Scholar (Winter 1968): 84-96.

- “Remembering Fanon.” New Formations 1 (Spring 1987): 118-135. Homi Bhabha, Stephan Feuchtwang, and Barbara Harlow contributed to a special section remembering Fanon on the 25th anniversary of his death.

Links to Other Sites

Isaac Julien’s Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask

http://www.newsreel.org/films/frantzfa.htm

Author: Jennifer Poulos, Spring 1996

Last edited: October 2017

12 Comments

Pingback: Resources | Liverpool Postcolonial Reading Group

“While Fanon charts the psychological oppression of black men, his book should not be taken as an accurate portrait of the oppression of black women under similar conditions. The work of feminists in postcolonial studies undercuts Fanon’s simplistic and unsympathetic portrait of the black woman’s complicity in colonization.”

Not only does that make his anaylsis morally bankrupt, hateful, and questionable, if a misogynistic man like him is supposed to represent “black people” as the “the damne/condemned” or “the condemned of the earth” what does that make Black women? It’s frightening.

This is a common dismissal of Fanon–one of essentialist. However, I think you are missing the point and conflating various ideas here. Wreathed of the Earth and Black Skin, White Masks, is part of a larger genealogy of the black radical tradition. Seminal work in understanding larger systemic structures of racism and colonialism. Any discussion of race in which ever context (e.g. gender, sexuality, class) must include a larger discussion of structural oppression. Most importantly, however, is that Fanon’s work follows the black radical tradition politics of escape, marronage, and abolition. In other words, the imaginings of an alternative. Before we get free, we must imagine its possibility. All, reasons why Fanon’s work reappears in black feminist scholarship.

Yea? Well maybe it’s about time some Black feminists stop making allowances and excuses for Black males like this in the interests of being fair and balanced. Maybe should totally discredit any Black male scholars who have the audacity to claim they can speak for the women they regularly dismiss and denigrate under their horrific, misogynistic, and thoroughly abusive and exploitative, color-struck, white female chasing, Black machismo based patriarchy. Many of us who have to LIVE with the domineering, overbearing hateful and misogynistic Black male scholars / intelligentsia who pull this crap are tired of it. You cannot be the “Wretched of the Earth” when you are clearly participating in the oppression of your own women. I don’t care what a Black feminist academic says: I refuse to have any Black males who can’t even recognize the basic humanity of Black women in patriarchal racist society blithely claim to represent “Black people” or “Blackness” anymore. It needs to stop.

Well said, Elle!

Thank you, Michelle.

i don’t think it would be fair to consider all the work of Fanon as a waste just because he didn’t defend the role of the woman in a black society,i beleive that his work swings toward a more psychological shape that defend the entire black race and any other race under oppression by attacking the oppressor,he did well deconstracting and dismantling the binary opposition of white and black,and he didn’t dive into the dilemma of gender that much,but still by defending the black race,im sure he defending both sexes,male and female,so Ellen,please let’s not genderize his work and accuse him of something i beleive he didn’t do.

@Issam He clearly DID NOT defend both sexes or did you not read the disclaimer where it said that he deliberately chose to paint an UNSYMPATHETIC portrait of black women being complicit with colonization. He cannot and does is not defending black women and he cannot any longer be construed as speaking for black women. Like many black male scholars from around the globe he should be known as the anti-black misogynistic, white woman chasing, unsympathetic, misogynistic BIGOT against black women that he was. If staying the truth about he completely misrepresented the DOUBLE and INTENSIFIED oppression of black women under colonization diminishes or destroys his legacy and scholarship, oh well. If people aren’t being coerced and manipulated into viewing anti-Jewish tracts from the Third Reich as being objective, rigorous scholarship about the Jews decades after the fact, then people shouldn’t have to view the anti-black misogynistic screed Fanon wrote as being objective, rigorous scholarship about “black people”, since black women comprise HALF of all black people and he was too biased and bigoted about them to write objectively. He basically painted black men as the biggest, most sympathetic victims of racism and colonization and gave credence to the idea that black women who deal with both racism and sexism at the hands of white men and black men, were aiding in the oppression and victimization of black men. He should have never been lauded this much as a scholar considering how he distorted the public image of black women under racist colonization, especially the black women from Martinique. I’m sure there are other more better, more thorough, and less biased scholars out there that can more appropriately speak about the TRUE conditions under racist colonization for black people, not JUST black men as though blackness = black men. Enough is enough.

Well-informed, well- discussed- well- substantiated, well-presented…

Is Fanon’s psychology really Black? If you remove racial references in a lot of his writing, his insights could make psychological sense, or not.

after having considerable and absorbed attention over the book of Frantz fanon, it may be said that it charts the role of language which transforms entire life of colonized and captives. it alludes the view that colonizer are responsible to make colonized feel inferior because of which they become completly involved into the imitation of the life style, given by colonizers or masters

Pingback: Assimilation (White Teachers, White Activists: Anti-racist Work #2) | Educate All Students, Support Public Education