In an overview of a combined research study performed by Connell, Lorber, Martin and Risman, the authors of “Sexual Assault on Campus: A Multilevel, Integrative Approach to Party Rape,” propose a series of changes that should be taken to prevent sexual violence in the party scene (Armstrong et al. 481). While the proposed changes could be considered logical with respect to the data provided, the specific circumstances that arose at this “large midwestern university” should not automatically be applied to all schools and probably aren’t the most likely to encourage change. The authors suggest a more integrated approach to campus housing, they encourage more balanced policing of places where students can engage in under age drinking, and the promotion of more socially acceptable non-alcoholic activities (Armstrong et al. 489). Education, of both men and women, is a critical aspect of sexual violence prevention and should begin prior to the arrival of freshmen. As we have learned, often it is the sexual script in which “men… pursue sex and women… play the role of gatekeeper,” (Armstrong et al. 488) that promotes the sort of ignorant view that leads to women blaming themselves or believing there will be stigma associated with coming forward. The truth is that education is not the only approach to this problem that needs an update. When you read between the lines, the authors have a pretty negative opinion about the effect that fraternities currently have on sexual assault.

Here at Emory, we are already a step ahead. We have relatively integrated freshmen dorms. We take alcohol awareness classes and are given sexual assault information before arriving for orientation. Every year they update the data they want incoming freshmen to know because we have the resources to combat and react to these kinds of incidents. The fraternities, while certainly not monitored 100% of the time, are policed very heavily during the most party heavy time of the year and monitored consistently throughout the year, especially in comparison to my freshmen dorm. There are plenty of non-alcoholic events offered and often, people do actually show up to them. Yet, despite all of these significant differences, Emory still has it’s own problems.

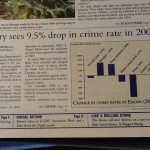

In recent news, Emory has had a significant rise in reported incidences of sexual assault and rape (Skibell). These issues obviously have to be addressed. However, it is my belief that the proposed steps lack the specificity to be directly targeted toward the Emory environment. Those proposals are inherently blaming the Greek system. While starting in the Greek system is a fully acceptable way to promote change, targeting this portion of Emory is not going to stop the violence. As noted in the Wheel article, two of seven reported incidents occurred in fraternity housing. I would say ‘only two’, but that would make it seem as though I’m trying to transfer the blame.

Our Greek community includes many campus leaders who participate in sports, community service and student government. Yes, there have been two reported incidents in which Greek men have been accused of sexual assault. And yes, there are more to come, because women are starting to feel more comfortable coming forward. But the more accusations that are reported, the more we are going to see that these incidents are happening all over campus.

The problem as I see it, is in the process of education. Encouraging young women not to drink until they have no self control is a great idea. Keeping in mind that young men are probably drinking as much, if not more, than their female counterparts, encouraging men not to take advantage of women is also a great idea. The problem is, there’s no question. The definition of consensual is simply not promoted in any form between our peers.

According to Emory policy:

“Consent is an affirmative decision to engage in mutually acceptable sexual activity, and consent is given by clear actions or words. It is an informed decision made freely and actively by all parties. Consent may not be inferred from silence, passivity, or lack of active resistance alone (Campus Life).”

When a friend of mine told me he was being accused of rape, I asked, “did she say she wanted to have sex with you?” His response, “Nah, but she was going with it…” He’s a really nice guy and I would never think him capable of putting a girl through that, but it’s a pretty common story. Plenty of girl’s go out with the full intention of making out on a dance floor and then it just goes too far. It’s not okay and I’m not proposing they are at fault because someone took advantage of them.

In all honesty though, I didn’t really expect him to say yes. After this class, I just know that’s the only way he could have protected himself. In speaking with my peers, I have found the predominant response to the idea of direct consent is disdain. Frequently guys will laugh at the idea of asking and girls will admit no one’s ever asked them.

I believe this one point could change a lot. There might still be sexual violence, but I think changing the approach to consent could transform the dangers of the party scene.

Armstrong, Elizabeth A., Laura Hamilton and Brian Sweeney. Sex Matters: The Sexuality and Society Reader “Sexual Assault on Campus: A Multilevel Integrative Approach to Party Rape” 2006

Skibell, Arianna. The Emory Wheel. “Seven Rapes Reported Since August” November 5, 2012

Campus Life. Emory Healthcare Policies and Procedures. Policy 8.2 Sexual Misconduct. August 16, 2012