by Joseph Vann-Jones

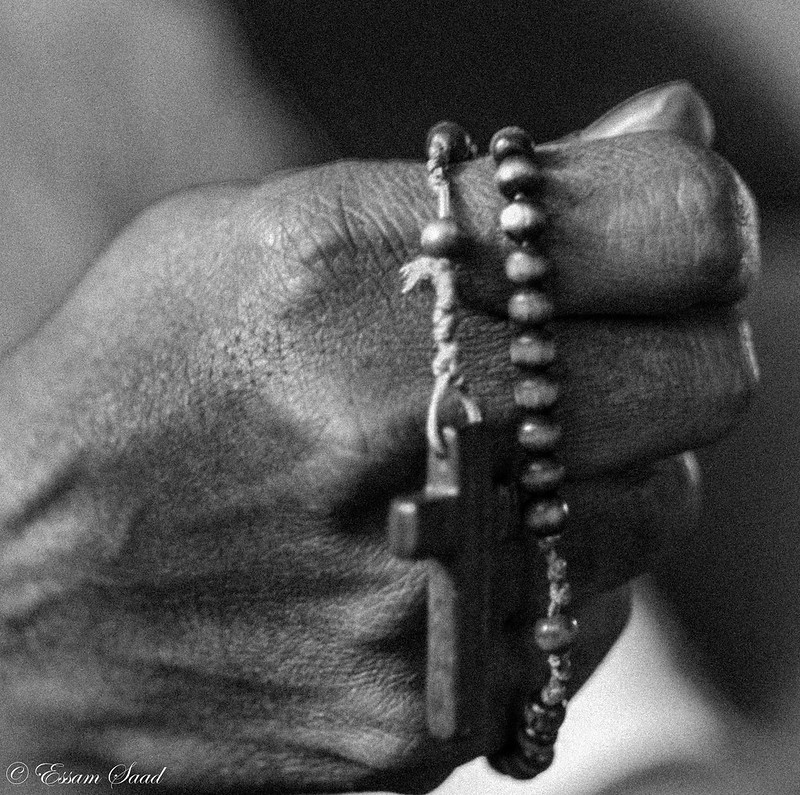

I remember hearing the congregation of Main Baptist Church singing, “When the world seems cold and your friends are few, There is someone who cares for you.” Even as a child, I understood the double-meaning of the song. The lyrics allude to Jesus caring for us, but it never explicitly says his name. Rather, someone cares for you. This resonated with me because I was acutely aware of the three realities that comprised my life: I am Black, I am Christian, and I am Gay. These three realities have also seemed to stand in contradiction with each other. People often ask, “How are you black and Christian?”, “how are you gay and Christian?”, and “how do you stay with a religion that seems to hate you?”. I later understood the underlying question in these inquiries— Why do you identify with communities who seem to not care about you?

The realization of this question led to a series of existential crises. Was I willing subjecting myself to harm, manipulation, and abuse? Blackness, gender, queerness, and Christianity are intersections that still remain in heavy tension. Black churches have been the nucleus of black communities up until the beginning of the 21st Century. These places were houses of worship and community centers, schools, banks, and even clinics. Black churches were places where black people found dignity and respect. These same churches were also places of misogyny and homophobia.

Today, Many black queer people attend black churches that will use them for their musicality or their money, but deny them of the thing they desire most— care. Queer people are occassionally the topic of the “gossip” after church and the subject of demonizing rants from the pulpit. They are sometimes denied ministerial positions, beyond the minister of music, and the main example around messages of “deliverance”. Many choose to leave these churches, but run into a series of other challenges in ministries that bear the title “open and affirming”. Many of these churches, if organized by black people, run into the challenge of caring for their trans members or the same theological limitations of the “conservative” churches, except on the topic of homosexuality. If organized by white people, open and affirming churches run into challenges with speaking about race and lack the familiarity and community of the black churches they left. Many black queer people feel like they must choose between their sexuality and their race when picking a black to worship because no one seems to fully care for them.

Pastoral Care should speak to these challenges. However, there is no book on black queer pastoral care. Black liberationist theologies often neglect queerness and minimize the necessity of care, while queer pastoral care fails to speak to the black exerience.

Where is someone who cares?

This question lead my mind back to the pew of Main Baptist Church and the chorus of the old song, “Someone who cares”:

Someone to care, someone to share

All your troubles like no other can do.

[They’ll] come down from the skies

And brush the tears from your eyes.

You’re [their] child and [they] care for you.

Black queer pastoral care must do the work of caring. Black queer pastoral care is that someone:

- Who must press Black churches to, openly, admit that their are queer people in their congregations and many of them are neither “hiding” nor feel like they should.

- Who must provide resources for the spiritual, mental, emotional, and physical needs of their queer parishoners.

- Who must help their congregations to be true safe spaces for their queer members.

- Who must challenge Black churches to change their ideologies around Shaming members who live beyond their own ideologies.

- Who must understand and speak to the communal nuances within black churches.

- Who must provide theological and non-theological education to their parishioners that highlights inconsistencies and myths.

- Who must understand that you don’t always need to “understand” a person to care for them. However, caring is best done with understanding.

- Who must understand the damage and danger caused by ostracism.

- Who must practice an unconditional ethic of love and challenge their congregations and communities to do the same.

- Who must understand the hostile environments that black churches nurture.

- Who must understand that there are people on different places of the sexuality spectrum

- Who must understand that discretion is not synonymous with secrecy.

- Who must know that caring for their queer members may initially present challenges and they may lose some members. That is okay and sometimes necessary in nurturing a healthy community.

- Who does not assume they know what a person needs.

- Who must openly hold their pastors and members accountable for their homophobic and transphobic rhetoric and ideologies.

This work is necessary because black queer people are dying— daily. Alone, they are dying. Ashamed, they are dying. Too soon, they are dying. Even alive, they are dying. They are dying in our hands because we did not and, often, do not care. There must be someone who cares?

2 Comments

Add Yours →You weave your own story and this song together so beautifully and painfully. The ways religious groups cling to identity markers and develop community without seeing everyone within them (white “affirming” church especially), and this question of “who cares” (and how) is one I will keep thinking on. Hope you have a restful holiday and break!

Joseph, thank you for sharing a little bit of yourself, here. The question your post leaves me with, is this: How can we invite/transform not only persons, but institutions to be more welcoming, more caring? Or, more to the point, can those institutions be strengthened in this work by drawing on the experiences and wisdom of persons who have encountered these layers of “contradiction” that you describe?