By Tayler Johnson for RE610: Be(com)ing Christian

Public and Theological Challenge: Is there a proper response to the suffering others and ourselves experience?

“God, why is this happening?”

“Why me? Why my family?”

“What is going on?”

“God, are you good?”

These were the first questions I shouted to God after my grandmother was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. These were the questions I shouted when my grandfather died after living with dementia for a year. These were the questions I asked God after my parents’ divorce and subsequent move away from friends and family.

I’m sure each of you has asked these questions and others. And if we are honest with ourselves, 2020 seems to be the year for them as we have experienced (and still are experiencing) a pandemic, an economic crisis, an election, as well as the deaths and murders of people including Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, Chadwick Boseman, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor, to name a few.

If you are looking for an answer to why we suffer, you will not find that here. Theologians over the past almost two thousand years have contemplated what makes suffering and the role of God in suffering.

But of course, if you have ever experienced suffering, you know that people will still attempt to give you an answer to this age-old question. Some of the answers I was told when my grandmother passed away included:

- “God needed another angel.”

- “Everything happens for a reason.”

- “She sinned and was being punished.”

- “God is testing your faithfulness.”

- “Don’t worry, God will not give you more than you can handle.”

Even writing these out still brings shivers to my spine. While I believe these things were said in good faith, these were not the things I needed to hear as I grieved my grandmother’s death. And I can envision that those currently grieving would not want to hear these responses either.

But what are we to do about it? For many people that try to explain the origins or purpose of suffering, it always ends with a great expectation of what is to come next. Perhaps you have heard something to the effect of “But it’s okay because one day there will be no more suffering. We look ahead to the horizon for the joy that only God can bring.”

I do not claim to be an expert on eschatology (the study of the end times) and I am part of a denomination (the United Methodist Church) that has not devoted much literature to the subject. John Wesley, the Methodist Movement founder, cared more about what is done in the present. For Wesley and his followers, the point of organized religion was to help people grow in their relationships with Christ and love for God and neighbor.

I think the same should go for how we respond to suffering.

My proposal is this: while there is no one correct response to suffering, Christians and churches should focus more on caring for the person(s) in their moments of need rather than on providing a long, theological answer to the problem of suffering. While the theological dimension is certainly needed for helping ministers understand what they believe about suffering, ministers more so need to know how to provide care as a first response to suffering.

So how do we care for a person in the midst of suffering?

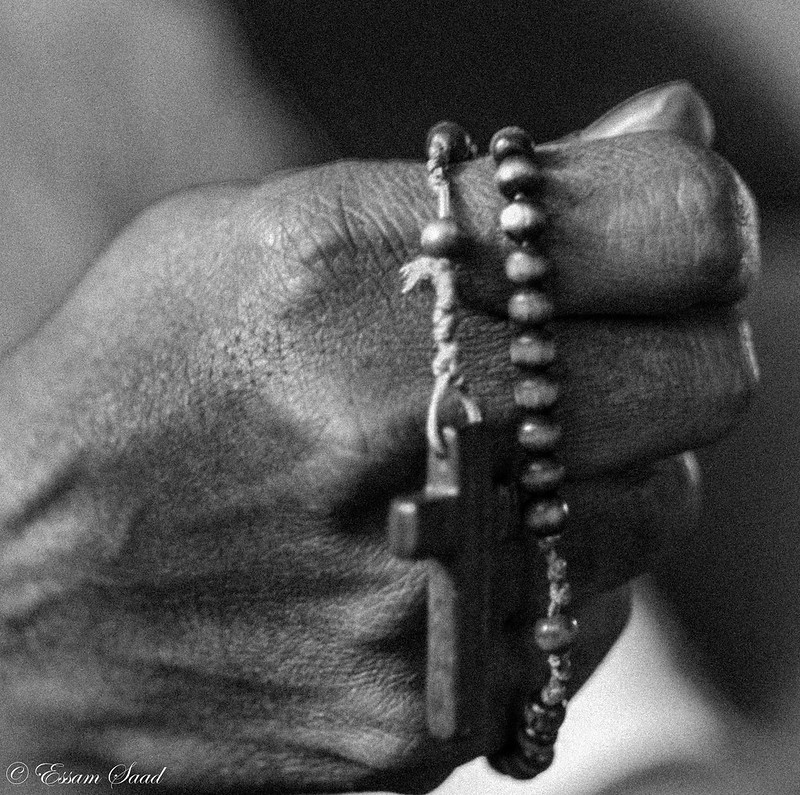

First, I think we need to recognize that suffering is both a personal and communal event. Suffering is personal because, for each person who experiences loss, they also lose a part of themselves and their identity. For each person, suffering is a loss of a relationship that threatens the intactness of that person. [1] Suffering is also communal in that a community or group of people share in collective suffering for the one that has passed. In this article from Psychology Today, Dr. Marilyn Mendoza writes about the role that celebrity grief plays in the lives of people who never met a recent deceased celebrity. [2] Another form of communal suffering is the pain and grief a community has when another person of color is murdered by the police. Before we can respond, we must be able to recognize what suffering is.

After this recognition, we need to respond by attempting to bring about nourishing life. Mary Elizabeth Moore, in her book Teaching as a Sacramental Act, writes on the theme of nurturing and how nurture can provide nourishing life. [3] For Moore, the call to nurturing life is mediated through God’s people as people are called to sustain life and pass it along. [4] These calls are lived as people seek to care for one another through supporting them and being present in their lives. Moore goes on to list a series of practice that each of us can begin doing to engage in nurturing life for those that are suffering [5]:

- Offer care for the immediate needs of an individual.

- Seek and reflect on life (look for the good in life as a way of reflection; seeking God in the midst of despair).

- Participate in forces of good (one way to care for an individual is to engage in acts of protest against injustice).

- Engage in story and ritual (create space for remembering those that have passed and allow others to express their suffering through narrative embodiments).

- Mentor (walk alongside, listen, and guide others).

The following is Kate Bowler’s list of things to never say to people experiencing terrible times and compliments Moore’s ideas greatly [6]:

The problem of suffering will never be fully answered, nor will it be satisfied for every person. But perhaps that should be reason enough for Christians, churches, and religious education to not focus on trying to answer the questions of pain and suffering. From a theological lens, Christians are called to love and care for their neighbor (Luke 10:27), which would imply focusing on the individual’s needs in the midst of their suffering. What if, instead, we took on attempting to care for the person in the midst of their suffering, not trying to provide answers to the question of suffering? Also, ponder this, what might nurturing life in the midst of suffering mean to you?

Works Cited

[1] Eric Cassell, The meaning of suffering (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 22.

[2] “Celebrity Grief: The Impact of the Death of Chadwick Boseman,” Psychology Today, last modified September 2, 2020, accessed November 14, 2020, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/ understanding-grief/202009/celebrity-grief-the-impact-the-death-chadwick-boseman.

[3] Mary Elizabeth Moore, Teaching as a Sacramental Act (Cleveland: The Pilgrim Press, 2004), 156.

[4] Moore, 165-166.

[5] Moore, 169-186.

[6] Kate Bowler, Everything Happens for a Reason and Other Lies I’ve Believed (New York: Random House, 2018), 93-94.

1 Comment

Add Yours →Tayler, this is such a wonderful and hard reflection. I’m sorry you lost a grandparent to pancreatic cancer – I lost my mom to that same illness in 2006. I used this Today show clip with Bowler in my Sunday school class. One of these things that makes me crazy about it is when Bowler finishes explaining why “God has a plan” is a bad theology, and the interviewer asks, “Where do you see God, now?” People really have a hard time just dwelling with another’s suffering!