In this Op-Ed, Friedman makes the argument that both parents, and the media, are overreacting to their teens’ self-reported anxiety levels. Friedman also disagrees that modern technology is influencing alleged increasing levels of anxiety in today’s teens. While he makes a compelling case against studies attempting to explain how technology affects anxiety in teens, we must also consider that this too is an opinion piece. Even if Friedman is correct in that teens’ clinical anxiety levels are not rising, his “pull yourself up by the bootstraps” view of the world is deeply troubling, and will only exacerbate the stigma against those who suffer from anxiety and other mental illnesses.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness’s (NAMI) statistical survey in 2016, 8% of youth have an anxiety disorder. Whether that percentage has increased or not with the current generation, those youth that are currently suffering are nonetheless subject to assumptions and stigmas surrounding their anxiety. Much like Friedman said, it is easy to feel that those with anxiety are simply overreacting to “normal” stressors. In my opinion, if an adolescent feels anxious enough to bring it up to a parent, knowing they will be faced with the stigma of mental illness, it is incredibly important to take them seriously and treat them as you would any other medical patient. When a patient comes in complaining of a headache, you ask them to rate their pain on a scale of 1-10. This self-reported number is subjective, just like the anxiety levels of a teen, but even if you doubt that their headache merits a “6,” you still treat them for their pain. Why should it be any different for those struggling with anxiety?

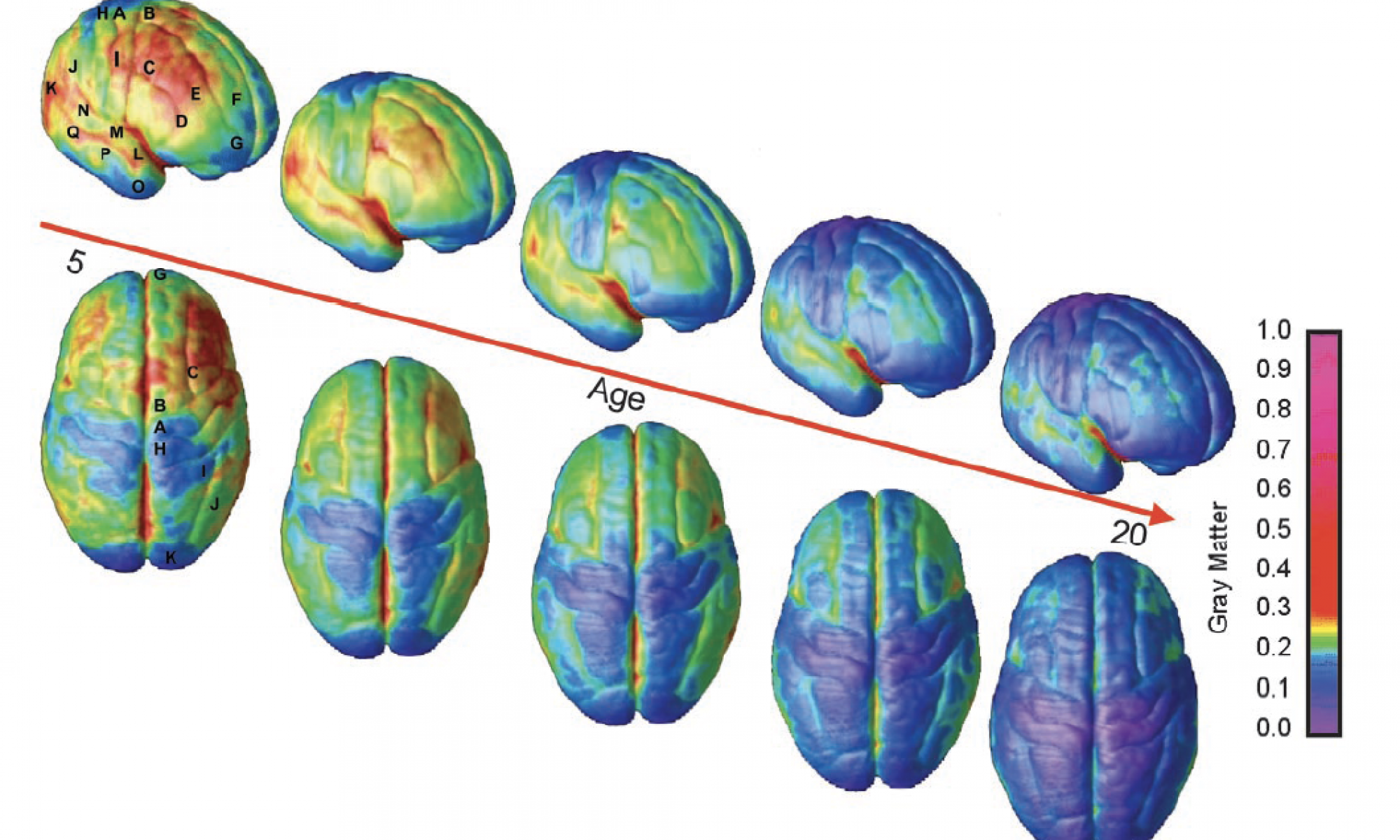

In another New York Times article by Friedman, “Why Teenagers Act Crazy” discusses how the early development of teenagers’ amygdalae, and the delayed development of the prefrontal cortex make teens especially susceptible to anxiety. He explains that while most adults have developed coping mechanisms for their day-to-day anxieties, teens are left practically defenseless. Therefore, having an adult like Friedman minimize teen anxiety to a “challenge of modern life” is not only condescending but incredibly problematic. We need to truly listen and believe teenagers, and allow them to express their emotions out loud without feeling like they are simply overreacting. In NAMI’s same statistical survey, it was reported that suicide is the 3rd leading cause of death in those aged 10-24, and that 90% of those who died by suicide had a mental illness. Taking teenagers’ emotions seriously is not only important, but could be life or death.

Friedman, Richard A. “Opinion | Why Teenagers Act Crazy.” The New York Times, June 28, 2014, sec. Opinion. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/29/opinion/sunday/why-teenagers-act-crazy.html.

“Mental Health By the Numbers | NAMI: National Alliance on Mental Illness.” Accessed October 30, 2018. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-By-the-Numbers.

Friedman, Richard A. “Opinion | The Big Myth About Teenage Anxiety.” The New York Times, September 7, 2018, sec. Opinion. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/07/opinion/sunday/teenager-anxiety-phones-social-media.html.