In an attempt to reconcile horrible acts of human rights violations, many countries have turned to Truth and Reconciliation Commissions (TRCs) as a means of transitional justice. We can differentiate transitional justice form other forms such as retributive, social, and restorative justice in that it allows “ a national community to move from the position of suffering egregious human rights violations and undemocratic rule to the return to the rule of law and some version of participatory democracy” (Perry and Sayndee 2015:xii). Given the historical use of violence and human rights violations in Africa, the use of transitional justice has been particularly prominent because of it goal of moving from corruption to democracy. The idea of justice has taken on its own identity in Africa, which results in a rich history of both successes and failures of TRCs.

What Are Truth Commissions?

The first truth commission that took place on the continent of Africa was in Uganda under Idi Amin in 1974. This was interesting because, while it was the first of its kind in Africa, Amin committed his own human rights violations and had no intention of using the information gathered from this commission. However, future truth commissions in Africa had actual goals of uncovering untold stories though various forms of justice (Perry and Sayndee 2015:xiv).

The African Charter on Human People’s Rights came to be in 1986 under the agreement of the Organization of African Unity. This charter was particularly important because it made the protection of human rights an international responsibility. It put the expectation on everyone to criticize human rights abuses. Also, this charter established the concept of human rights from an African perspective. This was very important as many Africans felt that they were criticized based on the western ideas of human rights which favored the individual, while their idea of human rights took the perspective of collective rights (Perry and Sayndee 2015:xii). The Charter certifies that:

Every individual shall be entitled to the enjoyment of the rights and freedoms recognized and guaranteed in the present Charter without distinction of any kind such as race, ethnic group, colour, sex, language, religion, political or any other option, national and social origin, fortune, birth or other status. (African Carter on Human and Peoples Rights)

With this precedent set, truth commissions took form in Africa.

Perry and Sayndee define truth commissions as “an investigatory body established by the state (or by a dominant faction within the state) to determine the truth about widespread human rights violations that occurred in the past; and to discover which parties may be blamed for their participation in perpetuating such violations; in order to investigate, over a specified period of time, a pattern of abuses, rather than a specific event” (2015:xiv). In this definition many of the core aspects of truth commissions are presented. They are victim-focused projects that contribute to the justice and accountability of those involved in the crimes committed in that country (Hayner 2001:28-29).

The decision to form a truth commission following a tragic period of history is very strategic as they are distinctly different from handling this in a court of law. We can distinguish truth commission proceedings from trials specifically in the fact that truth commissions don’t determine criminal liability of individuals (Perry & Sayndee 2015: xv). One of the big controversies with truth commissions is whether they are responsible for naming names once they essentially find someone guilty of committing human rights violations so that they can be tried in a court of law. The drawbacks to this come when there is a threat that individuals will not come forward and tell the truth in these commissions for fear of incriminating themselves (Hayner 2001:29). While trials focus on the individuals and uncovering their responsibility, truth commissions look at the large patterns of the overall event under investigation. They delve into the social or political factors that acted as the basis for the violence (Perry and Sayndee 2015: xv). Finally, rather than handing down a conviction of guilty or not guilty, at the conclusion of truth commissions recommendations are made based on discoveries of institutional structures or laws that have the potential to continue the violence previously experienced (Hayner 2001:28).

Why Use Truth Commissions?

“Bury your sins, and they will reemerge later.” (Hayner 2001:30)

Truth commissions have been so prominent in Africa because of their ability to facilitate political and/or social transition when the retribution is unlikely due to the expansiveness of the violence and the number of victims that were affected (Perry and Sayndee 2015: xii). In their essence, truth commissions are sanctioned fact finding missions. Many of the stories that are uncovered through this process are stories that have been silenced through history. By having these truth commissions, governments are essentially validating the lived experiences of the survivors. It starts with knowledge and move toward acknowledgement that something wrong was done, so that hopefully wounds can begin to heal (Quinn 2009:36). Their aim is to help to learn from the past and lead to justice through reconciliations.

Another important part of truth commissions has been determining institutional responsibility for the abuses. This helps to identify potential vulnerabilities within current institutions that could end up going down the same path. Also, the truth commissions contribute to identifying and holding accountable the specific perpetrators of crimes. For some victims this provides closure and allows them to identify someone if they were interested in giving forgiveness (Hayner 2001:29). Another function of the truth commissions that benefits the victim is their ability to establish the legal status of individuals who had ‘disappeared’. Previously, without a death certificate the families of these individuals could not access their wills or other possessions. In various countries the legal status of “forcibly disappeared” has been deemed by truth commissions and has been allowed to act like a death certificate. These accommodations, along with others, are some of the ways that truth commissions help to cater to the victims. In same cases they can go so far as make recommendations for reparations if reparation programs are established (Hayner 2001:28).

In the next sections we will dive into case studies of truth commissions that took place in Sierra Leone. Rather than trying to move past an authoritarian regime, this truth commission was established as a result of a very damaging civil war. Warning that some of the information that will be presented is graphic.

Case Study: Sierra Leone

The Civil War:

The conflict in Sierra Leone began, like many other African Nations, around the time they were granted independence from the British government in 1961. In 1967 the All People’s Party (APC) took control of the government, and turned Sierra Leone into a one party system by 1973. However, this party inherited a country that was already in economic trouble and with a government with little legitimacy. This made it easy for the rebel groups known as the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) to invade Sierra Leone at Bomaru from Liberian territory on March 23, 1991 (Bolton 2012:xvii). With this, the civil war in Sierra Leone began.

The war was caused by a general failure in the APC to provide for the needs of the people in Sierra Leone as well as other auxiliary issues. The RUF were notorious for their terror tactics of mutilation, rape, displacement of peoples, and recruitment of child soldiers. This was not to say that the state government did not commit any human rights violations of their own. Because of lack of organization and leadership, the state’s army also recruited children under the false pretense of immunity (Perry and Sayndee 2015:30). In both cases the children were ill prepared and basically sacrificed as manpower for this internal fighting. In 1996 the new president Ahmed Tejan Kabbah signed a peace deal with the leader of the RUF, Foday Sankoh. This deal was short lived and by 1997 President Kabbah was deposed and the now larger Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC), led by Major Koroma, took control of the government (Bolton 2012:xviii). This forced Kabbah to flee at which point he recruited the West African intervention force known as ECOMOG. ECOMOG was able to push the rebel military out of Freetown and in 1999 a ceasefire was established (Perry and Sayndee 2015:30).

In July of 1999 the Lomé Peace Accords were signed. This effectively ended the war, although it was not officially declared over until 2002 when the UN had disarmed the rebel fighters (Perry and Sayndee 205:31). Furthermore, the peace treaty included blanket amnesty for RUF fighters and established the plans for the Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission (SLTRC) (Bolton 2012:xix).

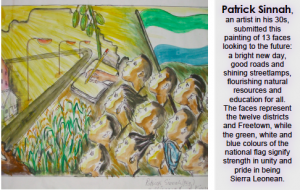

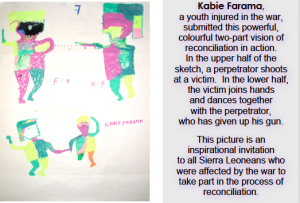

[source: Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report Volume 3b, Section 8]

The Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission:

Upon signing the peace treaty, the SLTRC was mandated to start within 90 days and was to make their official recommendations within a year. This established its importance and gave the truth commission credibility in its expectation to produce viable recommendations based on their findings. It was enacted in July of 2002 (Jalloh 2013:727). In a documentary of the SLTRC titled Witness to Truth, Bishop Joseph C. Humper, as the chairperson for the SLTRC, lays out the goals of the proceedings. The first is to “establish an impartial historical record of violation and abuses of human rights and international humanitarian law beginning on the 21st of March 1991 when the rebel war as it were began…to the end of the war as it were with the signing of the Lomé Peace agreement on the 7th of July 1997” (Witness to Truth 2004). The other goals that he mentioned were to address the needs of the victims and to promote healing in Sierra Leone.

In the documentary, victims give testimonies of their experience of the torture that they had experienced. They outline the groups that were particularly targeted by the rebel army, which included the affluent, the elderly, people of status, women, and children. A woman named Cecilia Caulker tells her story about how her son was the Sergeant General for the district in which they lived. Because of this status they targeted her family and forced Cecilia to watch them execute her son. She becomes emotional while retelling how she had to watch them cut open her sons chest as they pulled out his heart and forced a piece of it into her mouth. She was then nearly buried alive as the army officials tried to get her to reveal where her son had hid diamonds and other valuable items. After digging up the whole property they left (Witness to Truth 2004). Many more testimonies like this of torture were presented as the SLTRC. They were under specific instruction to listen to the stories of women, as well as children from the perspective of victim and perpetrator (Perry and Sayndee 2015:32).

At its conclusion, the SLTRC had collected around 8,000 statements from both perpetrators and victims. Although the initial peace treaty declared amnesty for RUF fighters, just before the start of the SLTRC a rekindling of fighting caused the United Nations to establish an international criminal tribunal to prosecute individuals who “committed international crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes, and other serious violations of international humanitarian law” (Perry an Sayndee 2015:31). In their final reports the SLTRC commissioners made their recommendations for reparations so that victims will receive support from the government. These recommendations included schooling or skills training and free medical care for children who were orphaned or abducted and victims of sexual violence. For amputees, they recommended that they receive free medical care, surgery and artificial limbs, rehabilitation services, skills training or education, housing, and a pension. For all victims they recommended that they receive trauma counseling and support. Finally they pushed that war memorials should be erected at specific locations around Sierra Leone. In an effort to obtain reconciliation, several perpetrators of violence made public apologies at the SLTRC.

Link to documentary Witness to Truth

Conclusion—Benefits and Drawbacks

When considering the use of TRCs as a form of justice in post conflict countries, it is important to consider the benefits as well as the drawback for undertaking such a large operation. Some of the benefits of TRCs were outlined in beginning as to why a country would use them. This included it being a way of acknowledging the suffering of victims and validating experiences that had been pushed out of history. But do these benefits outweigh the negatives such as the retraumitization of victims for public information. Without their testimony there is no purpose for a TRC, and by deciding to have one you force everyone to relive many of the traumas that they, themselves, may have been trying to forget. Likewise, many of the victims who provide their testimony already know the truth about what happened to their family members because they were there to bare witness to their murder. In these cases TRCs provide little benefit in terms of providing these individuals with new information (Hayner 2002:26). Also, many TRCs focus so much on the human rights violations that were committed that they fail to address the economic crimes and other large-scale corruptions committed by the government (Perry and Sayndee 2015:xix). With these factors in consideration, it is important to ensure that the results of the TRC outweigh the possible further harm to the victims of these terrible acts of violence.

[source: Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report Volume 3b, Section 8]

African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights, §§ 1-2-3 (Organization of African Unity 1986). Print.

Bolten, Catherine E. I Did It to save My Life: Love and Survival in Sierra Leone. Berkeley: U of California, 2012. Print.

Hayner, Priscilla B. Unspeakable Truths: Facing the Challenge of Truth Commissions. New York: Routledge, 2002. Print. (Woodruff JC580 .H39)

Jalloh, Charles. The Sierra Leone Special Court and Its Legacy: The Impact for Africa and International Criminal Law. N.p.: Cambridge UP, 2013. Print.

Perry, John, and T. Debey Sayndee. African Truth Commissions and Transitional Justice. Lanham: Lexington, 2015. Print. (Woodruff JC578 .P419)

Sitze, Adam. The Impossible Machine: A Genealogy of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan, 2013. Print.

Quinn, Joanna R. Reconciliation(s): Transitional Justice in Postconflict Societies. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 2009. Print. (Woodruff JC571 .R43)

Witness to Truth. Prod. Gillian Caldwell. Witness: See It, Film It, Change It. N.p., 2004. Web.