By Zakiya Collier

Filipinos began to mass populate the United States in the late 1700s. During this time, there were many laws in place to restrict their citizenship as Americans. First off, the Naturalization Act of 1790 stated that naturalization was only granted to “any alien, being a free white person who had been in the U.S. for two years.”[1]This statement racializes any Blacks and immigrants by using the rhetoric “non-white”. Moreover, it outwardly denies privileges of citizenship to these groups. The implications of this on Asian immigrants gave them no agency for political power and autonomy that would last generations to come. Later in 1924 the Immigration Act again denied citizenship to Asian-Americans but this time limiting the entry of “alien” individuals or those from Asian countries.[2] These policies deliberately excluded for the sake of discrimination. The United States believed it was best to have restrictions by means of controlling whiteness as a race.

From this school of thought, anti-miscegenation laws formed to further subjugate people of color and Asians to build barriers between races and strengthen the racial hierarchy in America. It was the Loving v. Virginia case of 1967 that finally constituted anti-miscegenation laws as illegal. Richard Loving was a white man and Mildred Loving was of a Black and Indian background meaning their marriage caused them to be guilty of a felony and five years of prison.[3] To deny this basic marriage right as a human and a citizen because of their race is undignified. I will be looking at Filipino-American intermarriage rates to analyze what it means to have a multiracial identity in society that rejects diversity. I would like to explore the facets of marriage in a cultural sense– what does it mean, especially in terms of racial and cultural identity, to marry another race? What cultural traditions of each race are preserved or comprised for the sake of the union? How can marriage across races influence your social capital? How does a biracial identity affect individual social awareness of the children?I will examine these questions concerning identity through a cultural lens to understand how this is internalization impacts first generation children.

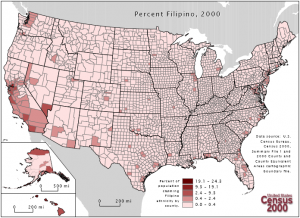

There are approximately 4 million Filipino-Americans living in the United States and in Seattle Filipinos are the second largest Asian group in the city.[5] There were about 4 periods of constant immigration to Seattle in the 20th century. America claimed Philippines territory in 1898 and from there allowed Filipino students to enroll and graduate from universities in America. President of the Filipino Student Association at University of Washington in Seattle, Rhea Panelo, interviews other Filipino-American students across campus to gauge what it feels for them to be a part of the American culture.[6] Viewers were informed of the duality of the Filipino-American experience as well as Filipino-American viewers gained a sense of empowerment. The major theme portrayed is a feeling of pressure to assimilate to American culture yet being resilient to these forces.

Drawing from data from the 2000 U.S. census, Filipino-Americans are more likely to marry Whites than other Asians when it comes to husbands and wives.[4] This indicates a want to increase status on the racial hierarchy ladder. As a Filipino-American, if you have a White spouse then you can benefit from their privileges and therefore increase social capital. This includes a higher socioeconomic class, better education, political agency, improved healthcare and more that is all stemmed from institutionalized racism. Marriage has continued to be a mode of survival for navigating a racialized society.

All in all, interracial marriages between Filipinos and Americans result in a union that will systematically help Filipinos navigate through a racialized society. On the other hand, this arguably denies their children access to their Filipino heritage through systematic rules resulting in the desire to assimilate-the cultural traditions are compromised. First-generation children have the unique experience of deciding how they want to be a part of society. They can either reject Whiteness and take on stereotypes of uninformed individuals or assimilate to Whiteness and strive to compete with them. Either way, Filipino-Americans are losing a sense of who they are and giving that power away of who they can be.

Sources

By the Numbers: Dating, Marriage, and Race in Asian America. (2013, May 1). Retrieved from https://imdiversity.com/villages/asian/by-the-numbers-dating-marriage-and-race-in-asian-america/

Eugenics, Race, and Marriage. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/eugenics-race-and-marriage

Imai, Shiho. Naturalization Act of 1790. (2013, March 19). Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 11:33, April 22 , 2019 from https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Naturalization%20Act%20of%201790/.

LEE, E. (2007). The “Yellow Peril” and Asian Exclusion in the Americas. Pacific Historical Review, 76(4), 537-562. doi:10.1525/phr.2007.76.4.537

Rhea, P. (2016, October 06). Retrieved April 14, 2019, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ED57pUP5YSY

United States Census 2000 (Ed.). (n.d.). Mapping Census 2000: The Geography of U.S. Diversity. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/population/www/cen2000/atlas/index.html