By Bea Conti

Although Whitewashing in Hollywood has existed since the inception of the cinema in the twentieth-century, the lack of racial and ethnic diversity in Hollywood has been a hot-button topic in recent years. Almost all minorities are underrepresented in Hollywood. Moreover, when they are represented, the storylines often fall into racist typecasting. African Americans often were typecast into roles as servants like Mammy (Hattie McDaniel) from Gone with the Wind if they had screen time at all. These roles were sometimes given to white actors who wore “black-face,” which was especially common in Vaudeville comedy acts. Micky Rooney infamously played the goofy Japanese landlord in Breakfast at Tiffany’s in what would now be considered “yellow-face.” Commonly, representations of people of color and minority groups in cinema have depicted overly exaggerated stereotypes and even racist attitudes. In addition, one could also argue that writers and executives are the gatekeepers in Hollywood in terms of who or what new ideas, especially as it relates to race, are included hidden under the guise of ratings and sales.

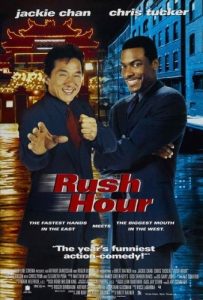

Several movies in the last few decades have worked to overcome these barriers of entry especially as China, the second largest movie going market, opened to foreigners in 1994. A movie like Rush Hour, released in 1998, rather than showing the “progressiveness” of Hollywood, demonstrated instead its reliance on traditional stereotypical tropes when portraying people of color. However, with a an Chinese lead man and an Black American lead man, the movie broke decades long rules on who could be leads in Hollywood. In addition, through the use of Jackie Chan, a popular Chinese actor, American audiences were introduced to Chinese media while Chinese audiences were introduced to Black Internationalism through Chris Tucker.

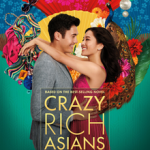

Newer releases like Black Panther, 2018, and Crazy Rich Asians, 2018, have further broken down these barriers for American audiences. Crazy Rich Asians, the first all-Asian cast movie since 1993 (The Joy Luck Club), gained the type of commercial and critical success usually reserved for white-culture dominated films. Both films center on the relationships between mothers and their children, especially in relation to their conflicts over traditional culture versus modern behavior. Constance Wu, the lead, told a reporter from Time magazine that “‘They [Hollywood] think we’ll say yes to anything and we’ll just be grateful…’ ‘We [Asian-Americans] are not supporting roles…We are stars on our own journeys.’”[1] Black Panther proved that a predominantly Black cast could lead a massive superhero blockbuster. Time magazine reported that “Rather than dodge complicated themes about race and identity, the film grapples head-on with the issues affecting modern-day black life.”[2] Further complicating the arenas of these two movies, both of which depict Black American and Asian American culture, has been their introduction to Chinese movie goers who do not experience the same racial tensions and minutia.

Through the films, Rush Hour, Crazy Rich Asians, and Black Panther, I explore the transnational nature of Hollywood films as they challenge and uphold stereotypical racial representation. In today’s ever-global-market, Hollywood needs to create empathy and greater understanding rather than depict dangerous and harmful stereotypes around Asian American and African Americans. By studying the history of black internationalism in Asia, through the lens of Hollywood, I explore how issues of access, participation, and control have been reflected in new and old media contexts to shape the relationships between African Americans and Asia throughout the years. As China, India, and African countries like Nigeria gain their footing in feature-length productions it becomes ever more necessary for Hollywood to respond and meet modern demands for inclusivity.

[1] Karen K. Ko, “Crazy Rich Asians Is Going to Change Hollywood. It’s About Time,” Time, August 15, 2018.

[2] Jamil Smith, “The Revolutionary Power of Black Panther,” Time, February 24, 2018.

Bibliography

Black Panther. Directed by Ryan Coogler. Performed by Chadwick Boseman and Michael B. Jordan. USA: Walt Disney Studios, 2018. Film.

Crazy Rich Asians. Directed by Jon M. Chu. Performed by Constance Wu and Henry Golding. USA: Warner Bros. Studios, 2018. Film.

Ko, Karen K. “Crazy Rich Asians Is Going to Change Hollywood. It’s About Time.” Time, August 15, 2018.

Rush Hour. Directed by Brett Ratner. Performed by Jackie Chan and Chris Tucker. United States: New Line Cinema, 1998.

Smith, Jamil. “The Revolutionary Power of Black Panther.” Time, February 24, 2018.