Out of more than 2,000 votes cast by visitors in a competition to rethink Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Memorial by Shane Neufeld and Kevin Kunstadt received the People’s Choice Award and was also awarded for consideration of scale by the competition’s jury. The memorial proposal draws on data from Slave Voyages’ Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, an open access archive (supported by the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship alongside several other institutions) that builds on “several decades of independent and collaborative research by scholars drawing upon data in libraries and archives around the Atlantic world” (see “About” page on SlaveVoyages.org). Neufeld has explained that the proposal “attempts to redefine how we perceive history through design, and specifically, to do so in counterpoint to the means and methods employed by the existing statues on Monument Avenue.” I spoke with Neufeld and Kunstadt to learn more about the project and the invaluable resource that Slave Voyages was during the design process.

The competition website also provides partial context for this task of reimagining Monument Avenue. “Designed to encourage the westward development of the City of Richmond, the original drawing of Monument Avenue showed a street accommodating a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee and extending west with a tree-lined grassy median. Developers unveiled the Lee statue on May 29, 1890, twenty years after Lee’s death. Building rapidly increased on Monument Avenue from 1900 to 1925 as prominent regional and national architects designed houses, churches and apartment buildings. As development extended west, the Stuart and Davis statues were erected in 1907, the Jackson statue in 1919, the Maury statue in 1929.”

By installing Confederate statues, the developer of Monument Avenue was not acting with the goal of honoring history, but instead sought to appease and attract white real estate owners. The myth installed alongside the physical markers told a story that was the opposite of truth and history. In an article for Medium, “Material Futures — Dismantling the Confederate Mythology,” Neufeld and Kunstadt write that many of those who oppose the removal of Confederate emblems remark that “we are erasing our history,” but that these arguments are based in fallacies, having nothing to do with “any kind of historical accuracy or an attempt at recording history at all.” If we really want to learn about the past, we “need to reckon with our collective history, but not in a way that mythologizes it, rather in a way that confronts the violence and original sins of this country’s past; which include both slavery and the genocide of indigenous peoples. Where are the memorials for these horrors? The memorials for all the lives lost and ripped apart by that violence? Who or what might we monumentalize as a role model within those narratives?” For the Monument Avenue competition, Neufeld and Kunstadt therefore sought to design a memorial that would replace these myths with facts, representing history more truthfully.

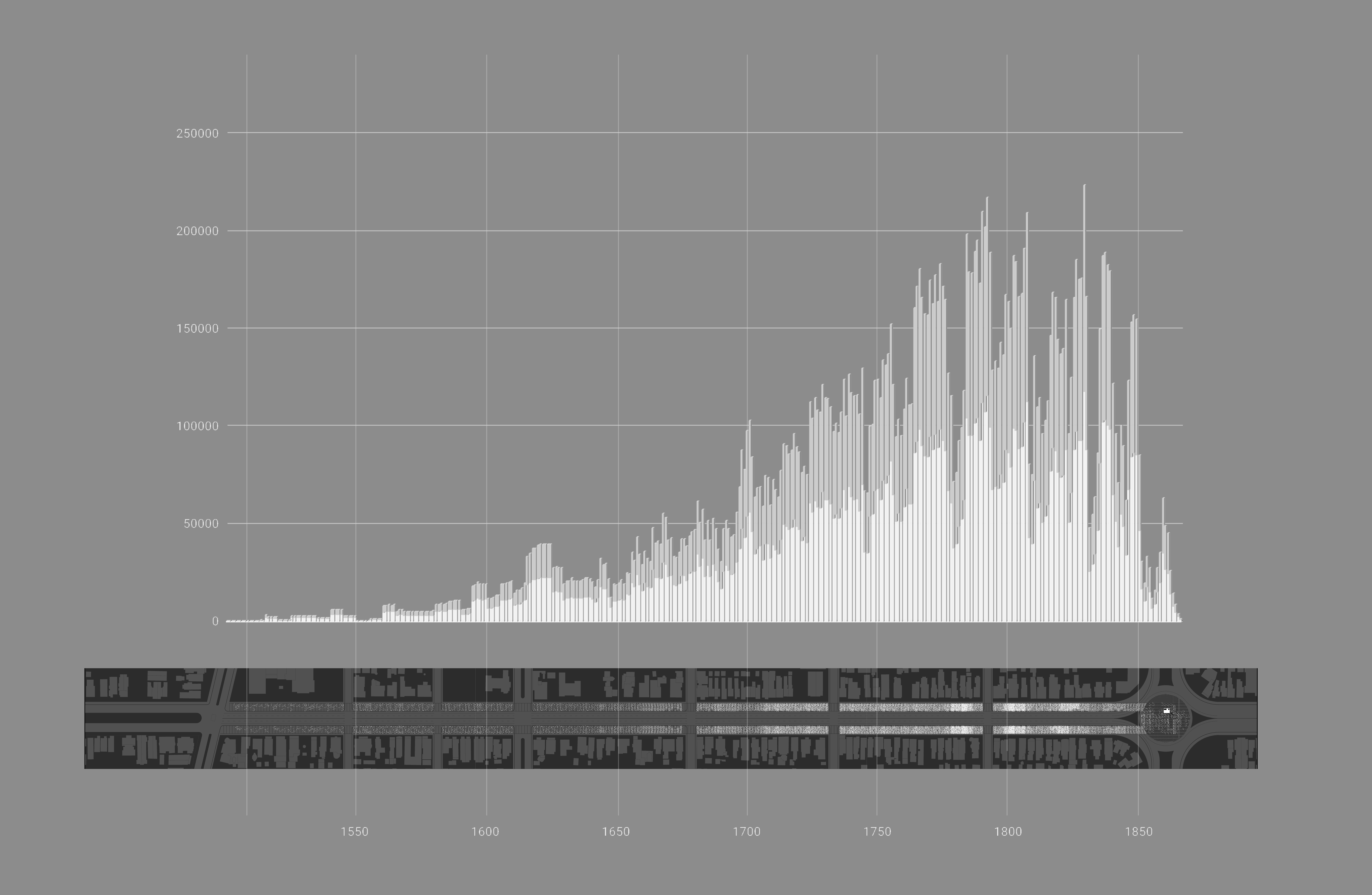

Upon doing preliminary research for their project, they stumbled upon the Slave Voyages databases, a resource that Kunstadt calls an incredible find: “The precision of knowledge was both moving and interesting,” and he emphasized the importance of being able to instantly download all of the data in an Excel spreadsheet. The database, among other important data variables, allows one to determine the individual number of abducted Africans per individual year, from 1514 to 1866. Such data made it possible for the designers to create an experiential timeline: an interactive, embodied application of the datasets. Neufeld and Kunstadt explained that experiencing visuals is another way of accessing data, and they hope that their design presents one way of thinking about the current social issues and representing data and history in a form that is useful and illuminating.

The following text (and the images accompanying this post) come from their competition proposal, providing more details about the project:

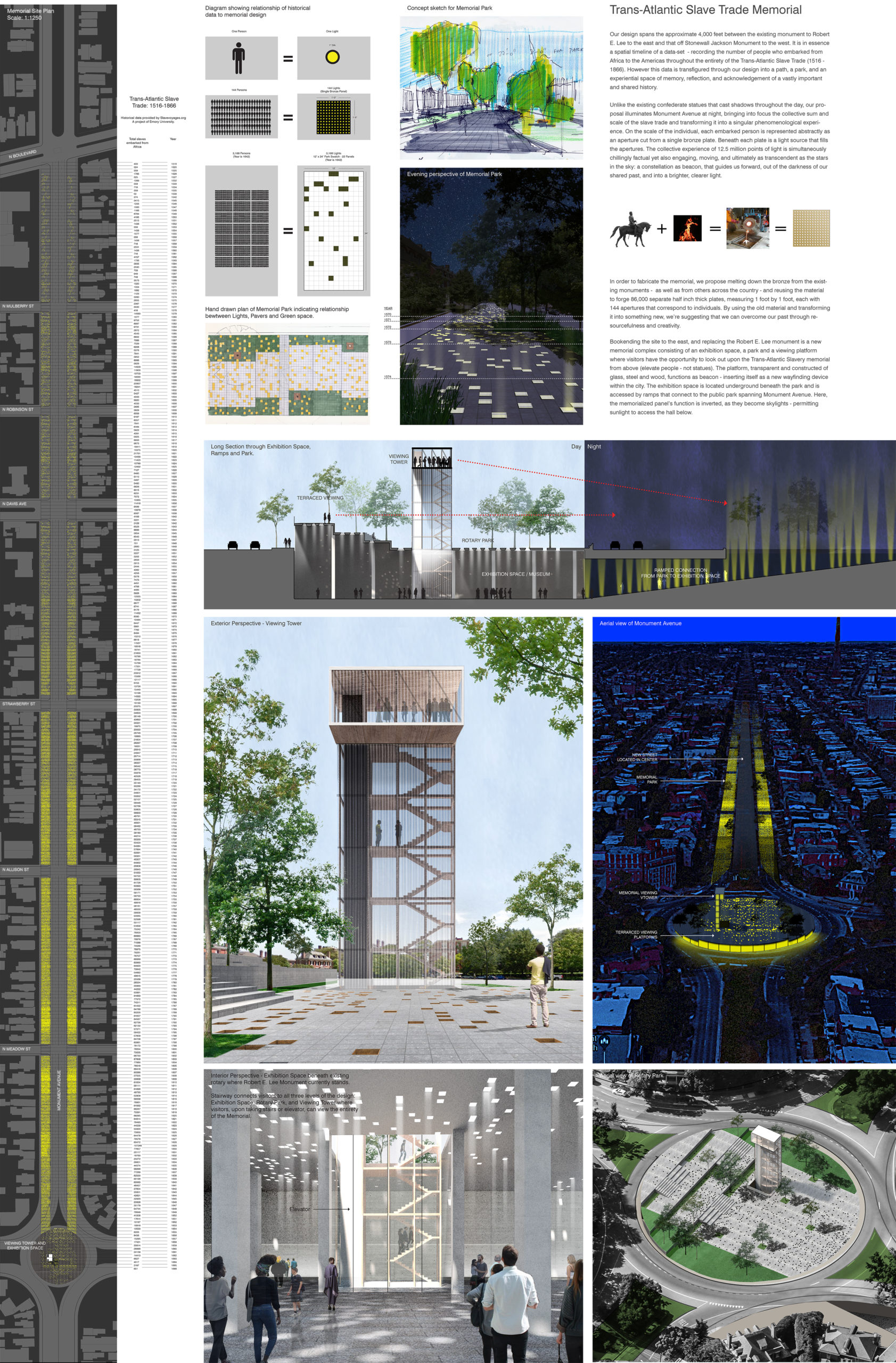

Our design spans the approximate 4,000 feet between the existing monument to Robert E. Lee to the east and that of Stonewall Jackson Monument to the west. It is in essence a spatial timeline of a data-set – recording the number of people who embarked from Africa to the Americas throughout the entirety of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade (1516 -1866). However, this data is transfigured through our design into a path, a park, and an experiential space of memory, reflection, and acknowledgement of a vastly important and shared history.

Unlike the existing confederate statues that cast shadows throughout the day, our proposal illuminates Monument Avenue at night, bringing into focus the collective sum and scale of the slave trade and transforming it into a singular phenomenological experience.

On the scale of the individual, each embarked person is represented abstractly as an aperture cut from a single bronze plate. Beneath each plate is a light source that fills the apertures. The collective experience of 12.5 million points of light is simultaneously chillingly factual yet also engaging, moving, and ultimately as transcendent as the stars in the sky: a constellation as beacon, that guides us forward, out of the darkness of our shared past, and into a brighter, clearer light.

On the scale of the individual, each embarked person is represented abstractly as an aperture cut from a single bronze plate. Beneath each plate is a light source that fills the apertures. The collective experience of 12.5 million points of light is simultaneously chillingly factual yet also engaging, moving, and ultimately as transcendent as the stars in the sky: a constellation as beacon, that guides us forward, out of the darkness of our shared past, and into a brighter, clearer light.

In order to fabricate the memorial, we propose melting down the bronze from the existing monuments – as well as from others across the country – and reusing the material to forge 86,000 separate half inch thick plates, measuring 1 foot by 1 foot, each with 144 apertures that correspond to individuals. By using the old material and transforming it into something new, we’re suggesting that we can overcome our past through resourcefulness and creativity.

Bookending the site to the east, and replacing the Robert E. Lee monument is a new memorial complex consisting of an exhibition space, a park and a viewing platform where visitors have the opportunity to look out upon the Trans-Atlantic Slavery memorial from above:

elevate people – not statues.

The platform, transparent and constructed of glass, steel and wood, functions as beacon – inserting itself as a new wayfinding device within the city. The exhibition space is located underground beneath the park and is accessed by ramps that connect to the public park spanning Monument Avenue. Here, the memorialized panel’s function is inverted, as they become skylights – permitting sunlight to access the hall below.”

The approximately 12.5 million holes of light (directly relating to the total number of embarked slaves) represent both the individual and collective toll of the Atlantic Slave Trade in historical context, and by re-forging from the Confederate statues, represents a change to transform the materiality of our past in a new way: throwing out myths, along with their physical representations, to now get it right. To walk through the memorial would be to experience the flow and density of the slave trade, to interact with a representation of how many years it spanned, how many individuals were abducted. The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Memorial seeks to clarify assumptions with architecture and experientiality. In response to those who would cry out against “tearing down history,” then the memorial says: “okay, let’s talk about history.” And more than talk about it, let’s represent historical data, grounded in the research and decades of work by scholars, in an embodied experience. As Slave Voyages indicates, the slave trade is “a vital part of the history of some millions of Africans and their descendants who helped shape the modern Americas culturally as well as in the material sense.” That part of history continues to shape Monument Avenue, the Americas, and the world to this day.

To learn more about the Slave Voyages databases, please visit: https://www.slavevoyages.org/