Are you a (social) Epidemiologist?

Category : PROspective

From Dr. Michael Kramer, Associate Professor, Department of Epidemiology

Are you a (social) epidemiologist? Should you be?

I am. A social epidemiologist that is. I was actually that long before I even knew what the combination of those words – ‘social’ + ‘epidemiology’ – even meant! Just as the notoriety of ‘epidemiology’ has risen in recent pandemic-tainted months (even my stoner neighbor knows what an epidemiologist is now!), so has the discourse around social epidemiology. It seems that the idea of unjust or preventable differences in health outcomes across the social dimensions that shape so much of our modern life – race, ethnicity, class, gender, geography, sexual identity, etc, etc – is having its ‘five minutes of fame’. Pundits, talking heads, and social influencers are suddenly speaking about, and wondering why, communities of color are bearing a disproportionate burden of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. Following the state-sponsored murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, it also seems that wide swathes of (white) America are opening their eyes to the longstanding existence of institutionalized and structural racial injustice that has direct (e.g. murder) and less direct (e.g. over policing and mass incarceration, segregation, racism in employment, education, healthcare, etc) consequences for the health of Black and brown communities.

So I ask again, are you a Social Epidemiologist? Or should you be?

Don’t worry, I won’t guilt you into being a ‘Social Epidemiologist’ (with a capital ‘S’)! However I will argue that if you do epidemiology you must be a ‘social epidemiologist’ with a little ‘s’, or else risk making (and re-making) mistakes that have littered the history of epidemiology and public health, and have the potential to cause harm rather than help. To distinguish what I mean between capital-S versus lowercase-s social epidemiology, let’s start by defining our collective work as epidemiologists.

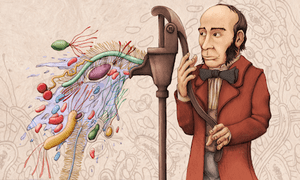

I like the definition of epidemiology from Modern Epidemiology (3rd edition, p 32): “Epidemiology is the study of the distribution and determinants of disease frequency in human populations” (emphasis added). This definition aligns nicely with John Snow, Cholera and our beloved Origin Story of epidemiology. Measuring the distribution of disease is about describing the who, where, when, and what of population health outcomes, whether infectious, chronic, behavioral or injury related. Describing the determinants of disease is about answering the questions of how and why disease varies between groups and over time. It is here we try to estimate causal effects of exposures or interventions.

Those of us who self-define as Social Epidemiologists are fundamentally epidemiologists. We work in pediatrics and geriatrics; in infectious and chronic disease; and in government, industry, or academic settings. While the health outcomes and occupational settings are diverse, the organizing principle of Social Epidemiology is exposure-oriented. We tailor the focus of our work to study of the social distribution and social determinants of disease. Describing social distributions of disease means intentionally conceptualizing, measuring and reporting disease occurrence along the social lines described above (e.g. race, ethnicity, class, gender, etc). Understanding the social determinants of health between and within populations also requires a shift in the exposures under consideration. Instead of individual behaviors, individual exposures, and inherited genes we might center our attention on social environments, racism & discrimination, political economy, social policy, and health policy as determinants of health overall and specifically of health inequities.

While the lessons of John Snow – careful observation, shoe leather detective work, intentional contrasting of competing hypotheses – are just as important for Social Epidemiologists as any others, we might look to additional role models as well. Although formally a sociologist, W.E.B. DuBois is arguably the founding father of social epidemiology.1 In The Philadelphia Negro, DuBois2 used systematic quantitative analysis to characterize health and social outcomes as they varied in 19th Century Philadelphia by race, employment status, and neighborhood segregation level. The modern Social Epidemiologist builds on this early work by recognizing that socially patterned experiences that occur through interpersonal interactions, in the non-random allocation of opportunity or exposure across one’s life span, and even across generations, are literally embodied as altered biological and psychological function.3 Our bodies express the health that is shaped by their continuous and accumulated interaction with a social world. It’s pretty fascinating and important stuff!

But what if Social Epidemiology (with a capital-S) is not your thing? That’s ok. Public health and epidemiology benefit from the big tent under which we all work. However choosing not to center your interest on social determinants of health does not diminish your responsibility to learn about and understand the use and misuse of socially constructed measures in the conduct of epidemiologic analysis. Let’s take, for example, the use of ‘race’ as a variable in epidemiologic analysis. Its use as a ‘confounder’ or even an ‘exposure’ has been ubiquitous across a wide range of study areas for many decades, yet very often the interpretation and meaning imbued into results from such analyses are poorly communicated at best, and in worse circumstances may represent lazy thinking and biased assumptions of the investigator, ultimately causing harm to population health.

While it is common to acknowledge that race is a ‘social construct’, there is often confusion about the implications of this idea for epidemiology. Does the presence of a ‘racial disparity’ in a health outcome mean some people are just born less healthy? Or if we ‘adjust’ for socioeconomic status should we assume that any residual racial difference is suggestive of a genetic cause? Or perhaps if race is ‘socially constructed’ we shouldn’t even be using these variables. Each of these conclusions has been made frequently in epidemiologic research, but rarely are they justified or well-supported either empirically or theoretically. Most of us align ourselves with multiple identities along the lines of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, etc. Few of us could honestly say that none of these dimensions have any influence whatsoever on our lives and health. Saying that these dimensions are ‘socially constructed’ does not mean they are not real in each of our lives; it simply means that they are not biologically essential, and therefore we would not inevitably expect differences in health simply because of these identities. So what do we make of a significant ‘effect’ of race from an epidemiologic model? That is a subject of ongoing discussion and debate, but one thing most social epidemiologists would agree with is that the interpretation is not simple or simplistic, as it has often been treated in epidemiologic research.

So even if you are defiantly not a Social Epidemiologist, I hope that you will take the initiative and opportunity to educate yourself on the obvious, and not so obvious, ways that population health and health inequities are generated. Learn about the debates about measurement and methods that concern social variation in health, and seek guidance when designing studies, selecting measures, conducting analyses, and interpreting results to reduce the chance that you unintentionally produce spurious or even harmful interpretations of results. At RSPH you can do this in many ways. There are elective courses explicitly in social epidemiology, but the issues of social drivers of the distribution and determinants of health are increasingly evident even in classes without the moniker of ‘social epi’. Talk with faculty, talk with other students, ask questions, but also listen closely. Perhaps we will not all choose to be Social Epidemiologists, but hopefully we can all agree that ‘social’ is critical to all of our work as epidemiologists.

1Sharon D. Jones-Eversley, Lorraine T. Dean. After 121 Years, It’s Time to Recognize W.E.B. Du Bois as a Founding Father of Social Epidemiology. The Journal of Negro Education. 2018;87(3):230-245. doi:10.7709/jnegroeducation.87.3.0230

2Du Bois W. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. University of Pennsylvania; 1899.

3Krieger N. Epidemiology and the People’s Health: Theory and Context. Oxford University Press; 2011.

Images Sources:

- https://i.guim.co.uk/img/static/sys-images/Guardian/Pix/pictures/2013/3/14/1363295337709/johnsnowillustration.png?width=300&quality=85&auto=format&fit=max&s=2bdd209b3e9da6c484216f5e69c6bf8c

- https://compote.slate.com/images/272b872f-3f99-4d4a-aa56-6a5b81d9c33e.jpg

Dr. Kramer is a social epidemiologist in the Department of Epidemiology with particular interest in maternal and child health populations and life course processes. His current research and teaching interests fall into three areas, and often include the intersection of these areas: Social determinants of health, maternal and child health, and spatial analysis.

1 Comment

Lauren Owens, MPH – 14PH

July 12, 2020 at 12:09 pmThanks for this, Dr. Kramer!