Contributed by Nadia Irfan and Joseph Birchansky

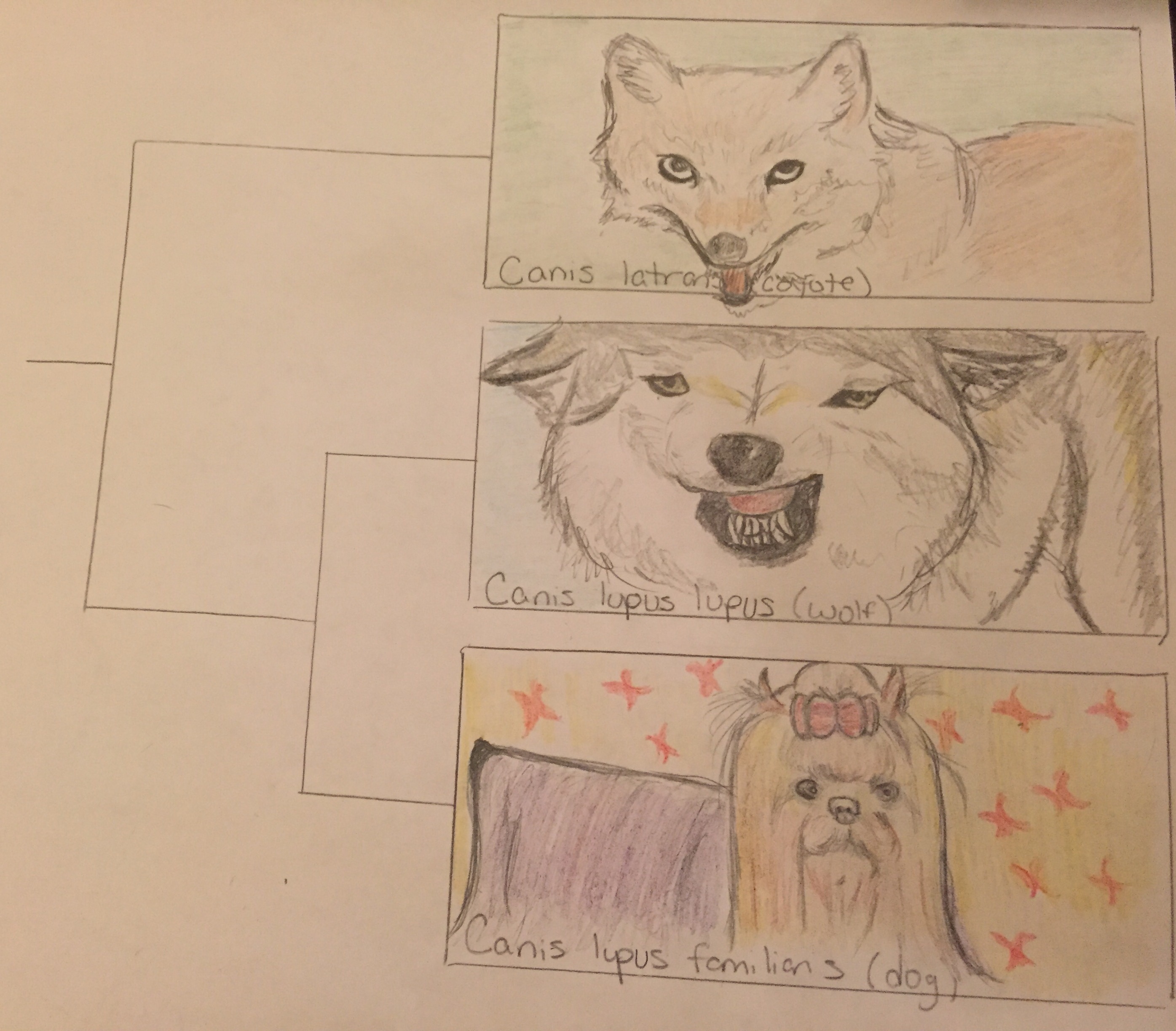

This is a graphic representation of the phylogenetic tree showing relatedness between dogs and wolves as it compares to outgroup (less related) species which branches off to form new species earlier on in history. The images show structural similarity and differences between the three species as well.

Dogs are the classic American pet, but how much do you really know about them? Dogs’ behavior is quite similar to humans’. For instance, even puppies that haven’t interacted with humans show social and cognitive skills on par with human children. This is surprising, considering their closest relative in the wild is the wolf, which is known to be more aggressive and less compatible with people. Wolves raised by humans don’t develop the same mental and social skills that domesticated dogs do. In addition, dogs are less fearful and more playful than wolves. This divergence is due to artificial selection by humans over many generations, which has resulted in dogs with improved tameness and temperament, which were reinforced by a population bottleneck – a significant reduction in population size.

Ancestors with dog-like characteristics originate in the fossil record up to 33,000 years ago. It appears dogs were first domesticated about 16,000 years ago, which actually happened before the development of agriculture. They then completely diverged from wolves 14,000 years ago, and there is evidence suggesting that dogs emerged from a single species of ancestral wolf. This divergence occurred via bottlenecks, significant reductions in population size, in both species, which were especially pronounced in dogs, from 32,000 to less than 2,000 individuals – a 16-fold reduction – and less so in wolves, which only experienced a threefold reduction. It is unclear why this reduction in wolves occurred, but it happened before humans began intentionally hunting them.

It’s interesting that, with so many behavioral and physical differences, dogs and wolves actually have very similar genomes. What’s different is which genes are being expressed, including those involved with cognition, memory, growth, and social skills. These differences in gene expression are driven in large part by artificial selection. Humans also influenced the morphology of dogs, including coat color variation, reduced cranial volume, and smaller skeletal size. These changes in morphology could potentially be deleterious because a possible effect of artificial selection may be a reduction in purifying selection, which ordinarily eliminates characteristics that are unfavorable in the wild. Research shows that humans may also have selected for behavioral traits, and these traits may have been selected for even before morphological traits. Not only did humans select for behavioral traits but food, shelter, and water availability given to them by humans are specifically responsible for differences in hypothalamic gene expression – a region associated with behavior and intelligence.

As a result of these selective pressures dogs have evolved different pack mentalities than wolves. Whereas wolves have a pair-bonded family unit that collaborates in hunting and rearing babies, dogs are less inclined to stay with one mate, are less active in raising their young, and are more dependent on human-provided resources. Overall, dogs’ and wolves’ different social, behavioral, and physical characteristics reflect speciation and domestication.

Also see: Who Helped the Dogs Evolve?

For more information, please refer to the following sources:

Albert, F.W., et al. 2012. A Comparison of Brain Gene Expression Levels in

Domesticated and Wild Animals. PLOS Genetics 8:9.

Freedman, A.H., et al. 2014. Genome Sequencing Highlights the Dynamic Early

History of Dogs. PLOS Genetics 10:1.

Li, Y., et al. 2013. Artificial Selection on Brain-Expressed Genes during the

Domestication of Dog. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30:8. 1867-1876.

Marshall-Pescini, S., Viranyi, Z, & F. Range. 2015. The Effect of Domestication on

Inhibitory Control: Wolves and Dogs Compared. PLOS ONE 10:2.

Ramirez, O., et al. 2014. Analysis of structural diversity in wolf-like canids reveals

post-domestication variants. BMC Genomics 15:.

Saetre, P., et al. 2004. From wild wolf to domestic dog: gene expression changes in

the brain. Molecular Brain Research 126:2 198-206.

Zhang, H. & Chen, L. 2011. The complete mitochondrial genome of dhole Cuon alpinus:

phylogenetic analysis and dating evolutionary divergence within canidae. Molecular

Biology Reports 38. 1656

HEY HEY its my comment

http://www.wp.de [url=http://www.wp.de]http://www.wp.de[/url]