Contributed by Aaron Karas, Yash Patel, and Kristin Larsen

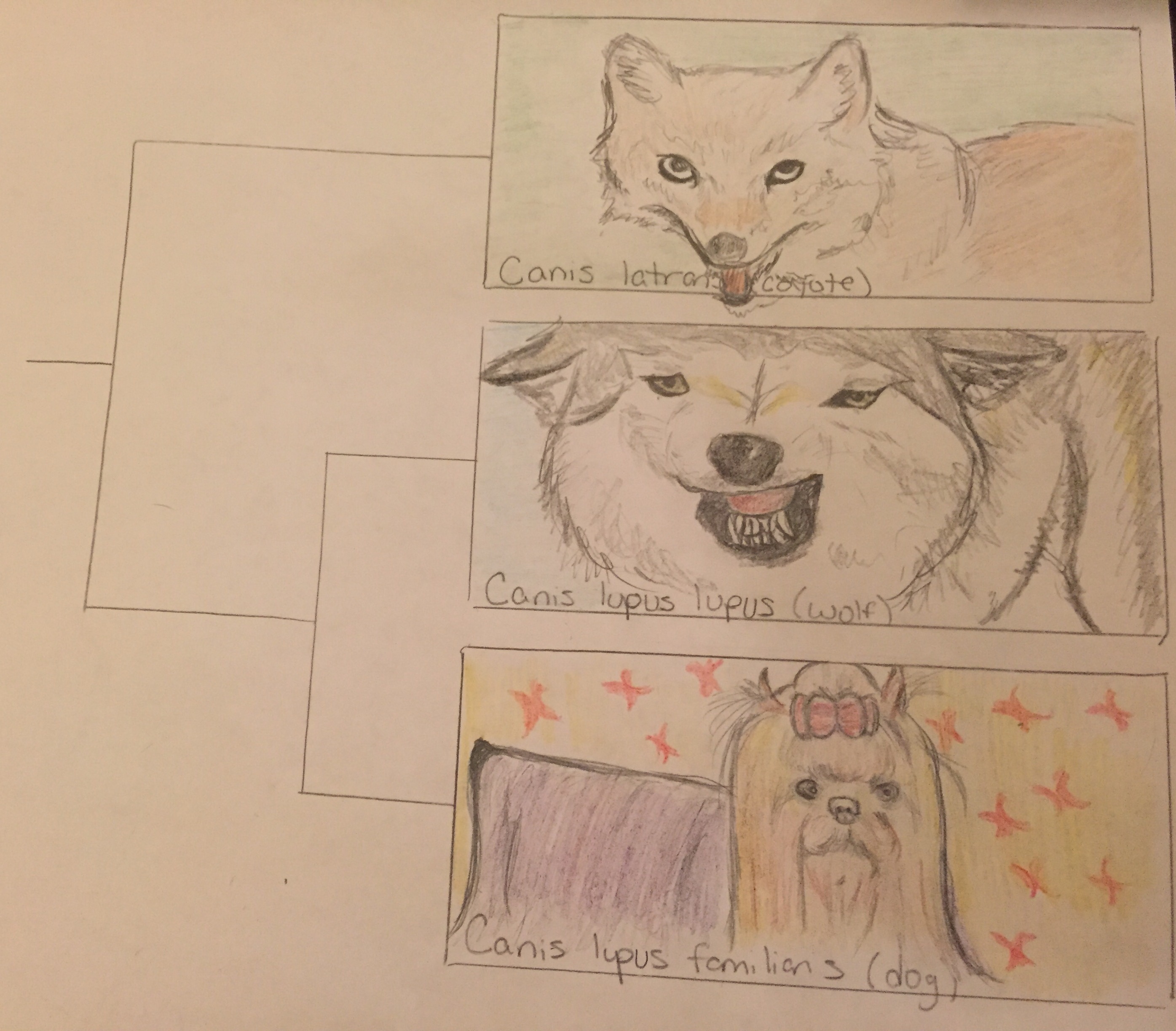

Have you ever wondered about the evolution of man’s best friend? Scientists believe it began between 30,000 and 130,000 years ago when humans began to control wolves. Today, as a result of mutation and artificial selection, there are hundreds of different breeds of dogs. Considering there are currently 339 breeds of dogs recognized by the World Canine Organization, it is easy to forget that they all belong to the same species. This profusion of breeds today reflects intense and purposeful interbreeding of dogs over the past 150 years.

The dog, Canis familiaris is a direct descendent of the gray wolf, Canis lupus. Genetic evidence from an ancient wolf bone discovered lying on the tundra in Siberia’s Taimyr Peninsula revealed that wolves and dogs may have split from their common ancestor at least 27,000 years ago. This first divergence was followed by what is thought to be the second divergence uncovered by research done in 2014. Ultimately this indicates that wolf populations from which dogs originated have gone extinct, and that the current wolf diversity from each region represents new, younger wolf lineages.

Since diverging from the gray wolf, the dog has undergone thousands of years of evolution. It may seem implausible that humans could have significantly altered the course of this species’ evolution considering this long time span. However, the idea that humans cannot influence evolution because it occurs over such long periods of time is a common misconception. Evolution does not necessarily occur over millennia. In fact, in some experiments it has been shown to occur in just a matter of weeks. In the case of dogs, a significant portion of the diversity that we see today can largely be attributed to the artificial selection that has occurred over the past 150 years. Artificial selection is the process by which humans intentionally breed a species with the hope of producing offspring with a particular set of traits. And this is what we see with dog breeding. Continued selection for certain traits within dog lineages eventually leads to the generation of new breeds, each of which has a unique form and personality.

For example, the German Shepherd breed first appeared in Germany in the late 19th century. The first declared German Shepherd was the result of decades of breeding dogs for the purpose of herding and guarding sheep. Desired traits, such as intelligence and strength, were thus being selected for. After continued selection for traits desired in a herding and guard dog, the German Shepherd evolved to become the notably territorial, loyal and attentive breed that it is today.

If you’re interested in learning more about this topic, please refer to the following articles:

Larson, G., E. K. Karlsson, A. Perri, M. T. Webster, S. Y. W. Ho, J. Peters, P. W. Stahl, P. J. Piper, F. Lingaas, M. Fredholm, K. E. Comstock, J. F. Modiano, C. Schelling, A. I. Agoulnik, P. A. Leegwater, K. Dobney, J.-D. Vigne, C. Vila, L. Andersson, and K. Lindblad-Toh. “Rethinking Dog Domestication by Integrating Genetics, Archeology, and Biogeography.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109.23 (2012): 8878-883.

Shannon, Laura M., Ryan H. Boyko, Marta Castelhano, Elizabeth Corey, Jessica J. Hayward, Corin Mclean, Michelle E. White, Mounir Abi Said, Baddley A. Anita, Nono Ikombe Bondjengo, Jorge Calero, Ana Galov, Marius Hedimbi, Bulu Imam, Rajashree Khalap, Douglas Lally, Andrew Masta, Kyle C. Oliveira, Lucía Pérez, Julia Randall, Nguyen Minh Tam, Francisco J. Trujillo-Cornejo, Carlos Valeriano, Nathan B. Sutter, Rory J. Todhunter, Carlos D. Bustamante, and Adam R. Boyko. “Genetic Structure in Village Dogs Reveals a Central Asian Domestication Origin.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2015): 201516215.

Parker, H. G. “Genetic Structure of the Purebred Domestic Dog.” Science 304.5674 (2004): 1160-164.

Skoglund, P., A. Gotherstrom, and M. Jakobsson. “Estimation of Population Divergence Times from Non-Overlapping Genomic Sequences: Examples from Dogs and Wolves.” Molecular Biology and Evolution 28.4 (2010): 1505-517.

Vila, C. “Multiple and Ancient Origins of the Domestic Dog.” Science 276.5319 (1997): 1687-689.

Akey, J. M., A. L. Ruhe, D. T. Akey, A. K. Wong, C. F. Connelly, J. Madeoy, T. J. Nicholas, and M. W. Neff. “Tracking Footprints of Artificial Selection in the Dog Genome.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107.3 (2010): 1160-165.