by Elena Perez

art by Victoria Amorim

Eerie music begins to play, fog fills the room, lightning strikes, and a man in a white lab coat exclaims, “IT’S ALIVE!” A figure sits up from the cold metallic examination table, only to look down at their body and discover it is not their own, but someone else entirely. You might recognize elements of this scene from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. However, in our story, the mad scientist is not Dr. Frankenstein but Dr. Sergio Canavero, an Italian neurosurgeon, and the creature is not a man brought back from the dead but someone who has experienced HEAVEN. To me, what Canavero calls HEAVEN seems more occult than it is angelic. The head anastomosis venture (HEAVEN) is a surgical procedure in which a head is transplanted from one body to another. Canavero claims the procedure could bring mobility back to people with quadriplegia (paralysis of all four limbs), restore quality of life for individuals suffering from neurodegenerative diseases such as Spinal Muscular Atrophy or Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and even pave the way for immortality. Some call him a visionary, others call him a nutcase. Although this might sound like an outlandish endeavor, never meant to escape the realm of science fiction, Canavero and his team have already made significant headway. When someone has a faulty organ, it can be replaced with a live organ transplant, so why would someone not have their head transplanted from a faulty body to a healthy one?

The Surgical Procedure

No easy feat, the 36 hour procedure would involve four teams of surgeons, each including a variety of medical personnel (surgeons of different specialties, anesthesiologists, nurses, and technicians) [1]. To begin, the teams would anesthetize, intubate, and cool the body of a brain-dead body donor and the transplant recipient to 15 degrees Celsius [2]. Deliberate hypothermia slows down metabolic processes, reducing inflammation and cell death, which allows the surgeons about one hour before tissue damage occurs [3]. Cutting both patients’ necks, the surgeons link the blood vessels from the head of the transplant recipient to the blood vessels of the donor body via tubes. The most critical phase of the procedure comes next, in a process called the GEMINI spinal cord fusion protocol, in which the doctors sever each patient’s spinal cord and place the head of the transplant recipient onto the donor’s body [2]. They use a substance called polyethylene glycol (PEG) as a “biological glue” to help promote spinal cord fusion [4]. Then, the team sutures the muscles and blood vessels of the head to those of the body. To assist the healing process, the patient is put in a medically induced coma for about one month, and the medical staff carries out extensive immunosuppression protocols to reduce the chances of the immune system rejecting the transplant [2].

Endless Possibilities versus Empty Claims

Over the past decade, Canavero has worked with Xiaoping Ren, a Chinese orthopedic surgeon, to refine the procedure and perform experiments on mice, dogs, and even human corpses [1,5,6]. As you can imagine, many medical professionals are skeptical of the feasibility of the procedure for a live patient. In response, Canavero and Ren emphasize that only 10% of descending spinal tracts (neuronal pathways that send motor signals from the brain to the spinal cord) are required for voluntary movement [7]. The GEMINI spinal cord fusion protocol, has a success rate of up to 20% reconnection, which Ren and Canavero have demonstrated is sufficient to allow some motor function in mice and dogs [2,5]. This is largely due to the use of an extremely sharp blade, which cleanly cuts each neuron’s axon in the spinal cord, and the use of PEG, which promotes axon reconnection. Before these techniques, animals who underwent head transplantation were left paralyzed from the neck down [8]. Although PEG-mediated axonal recovery is not perfect, the return of some motor control is a feat in itself. Even the subject surviving the procedure is an accomplishment. The ischemic period, that is, the time that the brain is without blood flow (due to induced hypothermia), can cause massive cell death. One mouse study by Ren shows 12 out of 80 mice surviving past 24 hours [9]. However unfavorable this might seem, a 15% survival rate for head transplantation in a mouse model would have been thought impossible 20 years ago.

As impressive as Ren and Canavero’s progress has been, the procedure still contains many practical limitations. While the GEMINI protocol does induce some axon regeneration, the effects of such minimal nerve recovery on the spinal cord’s many other functions, including the transmittance of sensory information, pain sensation, and proprioception are uncertain [10]. However, functional outcomes are of little importance if immune rejection occurs. Transplant recipients must take immunosuppressive drugs (often for the rest of their lives) to reduce the chance of the body’s immune system attacking and destroying the foreign organ or tissue [11]. Still a prevalent obstacle, about 85% of hand transplant recipients experience acute immune rejection within the first year [12].

Even if the immune response is controlled, coming to terms with having an entirely new body might make someone lose their mind. Transplant recipients frequently experience depression or psychosis as a result of mind-body dissonance [13,14]. The recipients of the first hand transplant and the first penile transplant can attest to this, as the severe psychological distress that ensued led to them having their transplants removed [15]. Considering that head transplantation is a more extreme change in appearance than a single organ transplant, critics argue that the procedure could drive patients to insanity and suicide [16]. Canavero contends that the “self is highly plastic and easily manipulatable”, so with a combination of immersive virtual reality (IVR) and hypnosis, the individual would psychologically adapt. Seemingly unfazed by the weaknesses of the procedure, Canavero continues in his pursuit to push the boundaries of modern medicine, proclaiming that every life saving procedure was deemed outrageous or impossible at some point [7].

Immortality Imagined

Canavero proposes that the surgery could be used to transcend the laws of man and let us live forever. In his book, Head Transplants and the Quest for Immortality, Canavero posits that by taking the head of an aging body recipient and transplanting it onto the body of a younger clone, a person’s life could be extended for up to 40 years [17]. Supposedly, the blood from the young body would have rejuvenating effects on the brain [18,19]. In his vision of the future, individuals would body swap with younger clones of themselves in an ongoing cycle [17]. At a press conference in Vienna, Austria, in 2017, Canavero said this:

“For too long nature has dictated her rules to us. We’re born, we grow, we age and we die. For millions of years humans have evolved and 100 billion humans have died. That’s genocide on a mass scale. We have entered an age where we will take our destiny back in our hands. It will change everything. It will change you at every level.”

As Canavero puts it, aging is genocide, and our only hope is HEAVEN. This places Canavero at the heart of the transhumanist movement, which advocates for the enhancement of the human race using science and technology to extend life spans and improve cognition [20]. It is human nature to fear death and fight against it, but it is also our biological nature to die. In disputing death, Canavero assumes himself a god. After Dr. Frankenstein’s monster comes to life, he exclaims, “in the name of God, now I know what it feels like to be God!” [21]. Perhaps delusions of grandeur are just the trademark of a mad scientist. But still, this begs the question, should head transplantation really be done, or has Canavero’s inflated ego clouded his judgment?

Cerebrocentrism in the Era of Embodiment

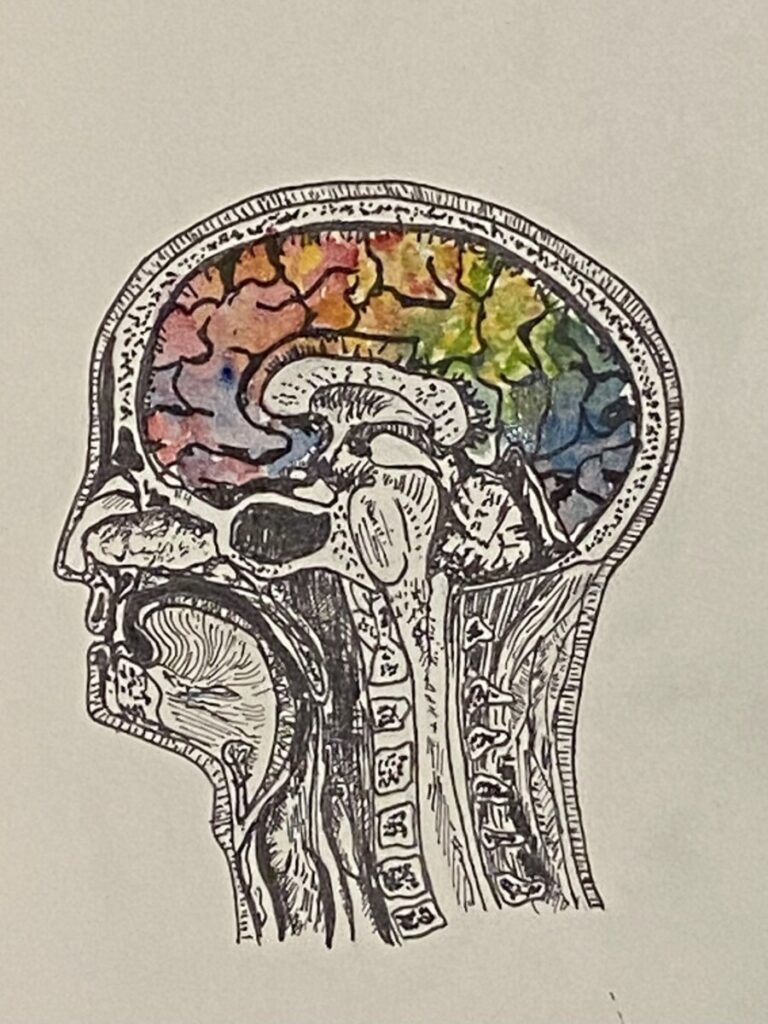

While head transplantation possesses many operational flaws, Canavero’s proposal suffers from one principal philosophical pitfall: cerebrocentrism [10]. Fundamentally, the HEAVEN protocol assumes that personhood, selfhood, and identity are localized to the brain. Thus, the body is merely a physical conduit through which the brain can interact with the external environment. Similarly, mind-body dualism, coined by 17th century French philosopher Rene Descartes, defines the mind and body as completely separate entities that can exist independently of one another. As Descartes famously said, “cogito, ergo sum,” meaning “I think, therefore I am” [22]. But are we actually nothing more than our thoughts? Consider the “brain in a vat” thought experiment proposed by Gilbert Harman, a 20th century American philosopher. Imagine your brain was removed from your body, placed in a vat, and connected to a supercomputer that supplied your neurons with all the same electrical impulses that your body normally would. Your “disembodied” brain would register these virtual stimuli as a conscious reality. Many philosophers have tackled the “brain in a vat” scenario to question how one can ever know that what they are experiencing is real and not just a bunch of electrical impulses from a supercomputer [23]. But I would like to pose the question: If you were just a brain in a vat, would you still be you? This thought experiment, as well as Ren and Canavero’s HEAVEN, work off of the assumption that a person is their brain. Or rather, the essence of a person is merely made up of electrical impulses and that the body is expendable to the human experience.

To me, this 17th century philosophy seems a bit out of date. We live in an era of embodiment, which recognizes that our bodies are integral to our personal identity and our experience of being. In many ways, our bodies characterize who we are, to ourselves and others, defining how we move throughout the world [24]. As Dr. Thomas Fuchs, a professor of philosophy and psychiatry, puts it in his book In Defense of the Human Being, the brain “is only the necessary, but by no means sufficient condition for personal experience and behavior. It is not the brain, but the living person who feels, thinks, and acts” [25]. Indeed, advances in the field of embodied cognition show us that our bodies influence emotion, personality, and identity in profound ways. For instance, the enteric nervous system (ENS), often called a “second brain”, controls the gastrointestinal tract, and has five times more neurons than the entire spinal cord [26]. Research shows that the ENS might have a significant influence over our emotions and mental wellbeing [27]. The gut-brain connection is further governed by the gut microbiome, referring to the collection of microbes (bacteria, fungi, and viruses) that live inside the gut [28]. Gut microbiota can influence sociality, perceptions of stress, and even the development of neurological disorders [29,30,31]. Although the roles of the ENS and gut microbiome in shaping personhood are not fully understood, evidently the body is integrated with cognition in complex ways. Ren and Canavero’s stance that bodies are transient frames that can be arbitrarily switched out without distortion to the self is an irresponsible one that completely disregards the prevailing rhetoric of embodiment.

Takeaways

Understandably, the prospect of functionally curing every disease or injury that does not impact the brain is enticing, however unrealistic. The 10 million dollar procedure strikes me more as a pompous passion project than an altruistic undertaking. Canavero’s radical and idealistic mission generates many more ethical dilemmas than one commentary can engage with; provoking questions about body sourcing, animal experimentation, and accessibility. This is not to say that there are no practical benefits to his work. Ren and Canavero’s advancements in the understanding of neuronal plasticity and axon regeneration in the spinal cord could be applied to helping those with spinal cord injuries, tens of thousands of which occur every year [32]. From a utilitarian perspective, the greatest good that could come of this research would be that which improves the lives of the most people [33]. But alas, Canavero is not a utilitarian, and perhaps neither are you. I urge you to consider the evidence presented here and decide for yourself: Is head transplantation ethically supportable? Should humans pursue immortality, and at what cost? Are you your brain, why or why not?