By Brooke Shalam & Ben Falk

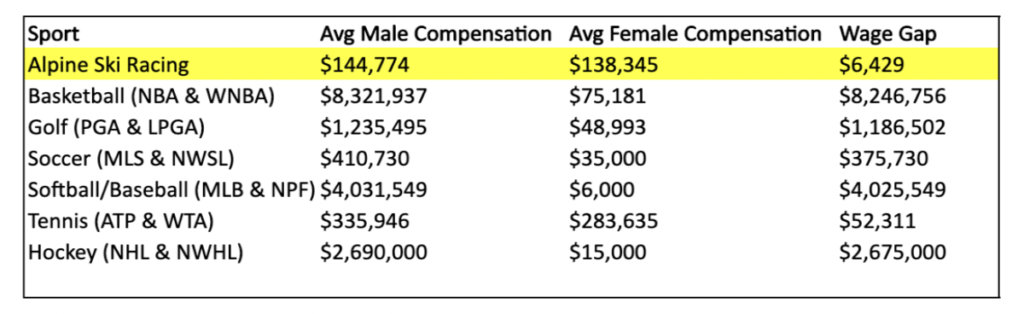

In a world characterized by pervasive gender inequity, there are relatively few spheres where women are compensated at a level that is on par or in excess of their male counterparts. The disparities of the corporate, entertainment and political worlds easily extend into professional sports. Within the realm of elite sports, there is little question that women rarely achieve the same level of pay, media attention, sponsorship or enduring fame as their male counterparts. Interestingly however, when it comes to annual earnings and prize money as well as media attention, females in the world of ski racing have fared considerably well, if not better than women in other professional sports. The table below outlines some of these disparities as of 2020.

Created by Brooke Shalam; data derived from: https://online.adelphi.edu/articles/male-female-sports-salary/

Compared to sports such as soccer, tennis, and golf, women’s ski racers have been arguably more fairly compensated for their wins. In fact, in the past two years, top female ski racers have out-earned male ski racers in prize money and annual compensation. These data points beg the question as to why? Why is a niche sport such as ski racing characterized by greater degrees of economic gender equity compared to its perennial counterparts?

To answer this important causal question, various unique and differentiating factors must be considered, including the individuality of competition, the geographic location of the field of play, the correlation with sovereign wealth, and the graceful nature of the sport.

Individual Nature of the Sport

One of the most significant factors driving the unique status of women’s’ earnings in skiing is the individual nature of play. It is well understood that fundamentally individual sports tend to have far smaller disparities in pay among men and women than team sports. As an example, women in the WNBA in 2015 earned between $38,913-$109,500 whereas their male counterparts in the NBA made between $525,093-$16.407mm during the same time period. Basketball is not the

only team sport where this stark imbalance exists. In the same year that these WNBA players were making seven or less cents for every dollar their male counterparts made, the 2015 Women’s Soccer World Cup prize money of $13.6m was a mere 1/30th of what prize money was for the Men’s World Cup tournament the year before. This works out to three cents per dollar earned by the male teams. Rounding out the magnitude of wage gaps in team sports is women’s softball, where the median salary is $44,680 compared to $1.15mm in men’s baseball or a ratio of four cents per dollar. While not perfectly comparable, skiing, in relation to team sports such as basketball, soccer, and softball presents a far slimmer wage gap. This narrower wage gap appears to have been present since the very inception of professional ski competition.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, professional women skiers were paid 30 cents for every dollar that male professional skiers received. While not on par, this early differential is a far cry from the three to seven cent figures that females in team sports receive today. This phenomenon is not limited to skiing alone. The additional compensation that individual athletes garner extends beyond just skiing. In the year 2000, the top 10 female golfers earned 36 cents for every dollar that the top 10 male golfers made, and in that same year, the top 10 female tennis players earned 67 cents for every dollar that the top 10 male tennis players earned. This data corroborates the clear takeaway that the individual sports such as skiing, golf or tennis consistently have a far smaller wage gap than team sports. A commonly accepted premise for this differential comes down to simple math. When athletic participants do not share their earnings or are not locked into a range applicable to an entire team, the per capita compensation of participants can be higher, even if the total pot of available earnings is lower. In addition, individual sports allow top participants to enjoy greater name recognition. While teams enjoy great organizational branding, individual competition typically allows star performers to be more easily identifiable and therefore capture a larger share of earnings. As a result, the individual nature of ski competition, along with various other peer individual sports, plays a critical role in the degree of compensation that its athletes can receive.

Who are the Top Individuals of the Sport?: A Women’s Spotlight

Mikaela Shiffrin

If one wants to talk about one of the most decorated and remarkable female athletes ever, Mikaela Shiffrin is undoubtedly a frontrunner in the conversation. Shiffrin was born in Vail Colorado in 1995. With both parents being former ski racers, it was not long before she started skiing, doing so in her driveway at the age of two years old. Her storied career began very early. At age 14 she was already winning competitions around the world. Since then, she has had a remarkable run. Shiffrin prides herself in being a top performer in multiple skiing disciplines. In FIS Alpine Ski World Cup racing, the top ski competition throughout the world, she made her first appearance in 2011 when she was 16. She went on to be the youngest American Ski racer to win a globe or the top award. She has appeared in every FIS World cup since 2011, where she has been a top annual performer every year and fierce competitor, winning 11 World Cup Titles. In 2013 she won the world slalom title at the FIS World Championship. Moving onto the Olympics, she competed for the US in 2014 and 2018. In 2014 she won a gold medal in the Slalom event at the age of 18. In 2018 she won another gold medal in the Giant Slalom event and a silver in the combined category.

Mikaela’s outstanding feats have prompted generous compensation. According to FIS, for the past four years, Mikaela Shiffrin, along with Lindsey Vonn (discussed below) and a handful of some of the world’s top competitors have consistently out-earned their male counterparts. Much of this success can be attributed to the fact that, since female ski racing’s inception on the global stage, ski racing has remained one of 35 professional sports to require equal minimum prize money among genders. This novel but practical rule makes equal pay among competitor groups far more feasible. Apart from endorsement deals which have proven to be rather subjective, as long as females choose to compete in any given race, they have an equal chance to earn the same prize money as their male counterparts. In fact, in 2019 Shiffrin became the first ski racer, both male and female, to achieve over one million CHF in prize money. As important, Shiffrin has advanced women’s roles in skiing and across sports in general. She once remarked “I’m proud to be part of a sport that has no gender pay gap.” She wants to show young girls that there is a future of equality for women in sports and that she is proving it. Shiffrin is young and she says she is still developing her opinions, but thinks it is important for young women to speak up about their beliefs. Shiffrin is an inspiration to women, men, and all athletes, continuing to push herself past traditional and physical boundaries. She once said “It was one of my big goals to win in every discipline when I first started racing!” She is certainly not done yet.

Lindsey Vonn

The acronym G.O.A.T. (Greatest of All Time) is thrown around a lot in the sports world today. While often used in a gratuitous manner, in skiing there is no other GOAT than Lindsey Vonn. Vonn was born in St.Paul Minnesota in 1984, starting to ski at the early age of two. She first learned how to ski from her grandfather. At the age of seven she was skiing year round. Lindsey said “I began racing at seven, and by nine I was doing international events.” Her talent was so apparent that her family packed up and moved to Vail Colorado. At 15 Lindsey competed in her first top-level event. She won her first FIS event in 2001 and also competed in her first world cup event at that time. During 2005 and 2006, Red Bull Energy presented Lindsey with a special opportunity to have a specialized training system customized to her needs. She said “I didn’t need to think twice. I had a feeling this was going to be my big chance.” In 2015 she became the most successful downhill skier of all time and never looked back. With 82 World Cup victories, she is the winningest female skier of all time and in second place among all men and women behind the legendary male skier, Ingemar Stenmark. Vonn competed in the Olympics in 2002, 2006, 2010, 2014, and 2018 where she became a three time medalist with one gold and two bronze medals. In addition to being one of the top ski competitors of all time, her talents extend well beyond ski racing. She is involved in women’s rights and released a book in 2016 called “Strong Is The New Beautiful.” Vonn says “All shapes and sizes are beautiful – the important part is your perception of yourself.” In addition, she is a fitness influencer who prioritizes strength and health and is also vocal in the crossover between politics and athletics. Moreover, Vonn, a strong voice in the feminist movement, breaking down barriers each day. Her unrelenting strength has manifested in both her best and worst moments. In the peak of her career in the 2013-2014 season, she dealt with some of the worst injuries experienced by ski competitors and yet, always persevered through adversity. Lindsey Vonn retired from ski racing after 2019, but her legacy is here to stay.

Like Shiffrin, Vonn’s impressive accomplishments have merited a glamorous paycheck. In the past decade, Vonn has consistently gone back and forth with the top male skiers in the field for who earned the most. In addition, in the past few years, Vonn has hit the jackpot on lucrative endorsement deals with redbull and other big names that have continued to help her generate even more money relative to her male counterparts, all doing so despite her recent retirement. However, while Vonn has accomplished a great deal in the world of ski racing and has been compensated accordingly, in an interview with CNBC, Vonn famously illuminated the single biggest flaw in the way ski racing pays its athletes. While Vonn, Shifferin, and some of the other top female athletes in the field have matched or even out-maneuvered their male counterparts in the past decade, many racers who fall below the top ten benchmark struggle to even reach ends meet. This unfortunate reality rings true for both males and females ski racers alike, and is a major downside to individual sports. Unlike team sports where pay is more evenly distributed, the individual nature of ski racing is undoubtedly both a blessing and a curse.

Nonetheless, it is top female athletes like Mikaela Shiffrin, Lindsey Vonn and others within the sport of ski racing and many individual sports alike that receive the limelight whereas many star athletes in team sports go unnoticed. Perhaps this very human tendency to praise individual athletes over those in team sports explains why females in alpine skiing fare better economically than those in other sports.

The Geographic Location of the Field of Play

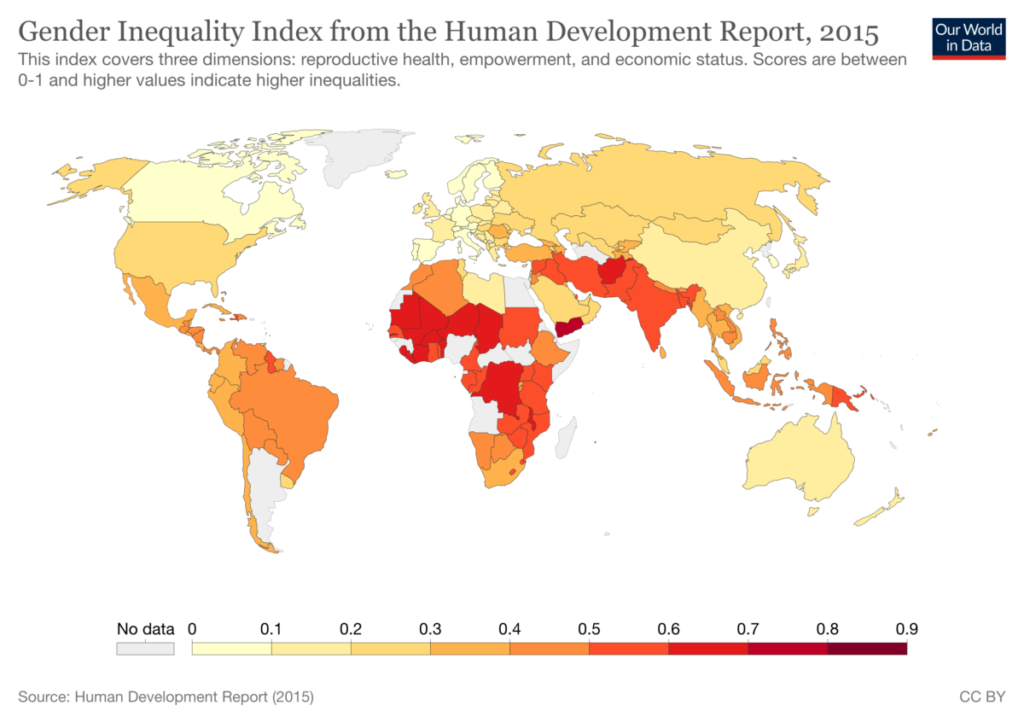

When seeking to differentiate causal factors for gender gaps amongst various sports, geographic breakdown of the field of play is key consideration. While the intrinsic nature of any particular sport itself (e.g. difficulty to play, contribution effect of star players, excitement to watch, etc) might be the reason as to why some sports compensate female participants better than men, it is often gender dynamics in the areas where the field of play occurs that provides some of the best clues for how compensation will be earned. As outlined in the graph below, females in the darker colored red regions throughout the world- particularly those residing in Arab regions, South Korea, and India have significantly higher levels of inequality in all walks of life. Specifically, these regions have the lowest levels of female government representation, cell phone access, employment and education coupled with the highest levels of domestic violence and discrimination. By contrast, in more developed countries, women enjoy much greater equality with men. In some countries, such as Iceland which has ranked first in the gender inequality index for ten years in a row, gender pay gaps are actually illegal. As a consequence, sports originating and being predominantly played in regions with high degrees of overall gender equity are likely to have much smaller pay gaps. With that, it is merely impossible to reference the gender pay gap associated with various sports without identifying and properly understanding the degree of overall gender inequality that exists as a backdrop in the specific regions where the sport is most popular.

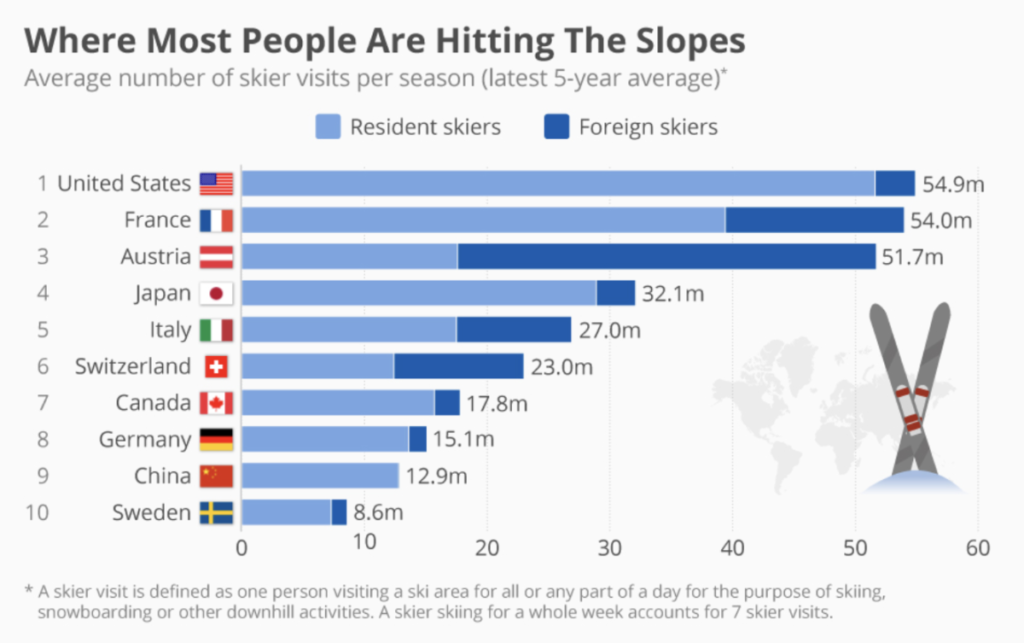

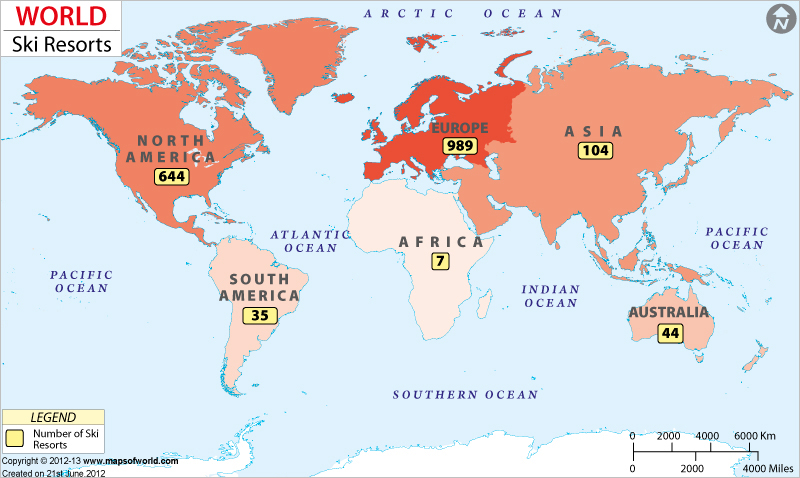

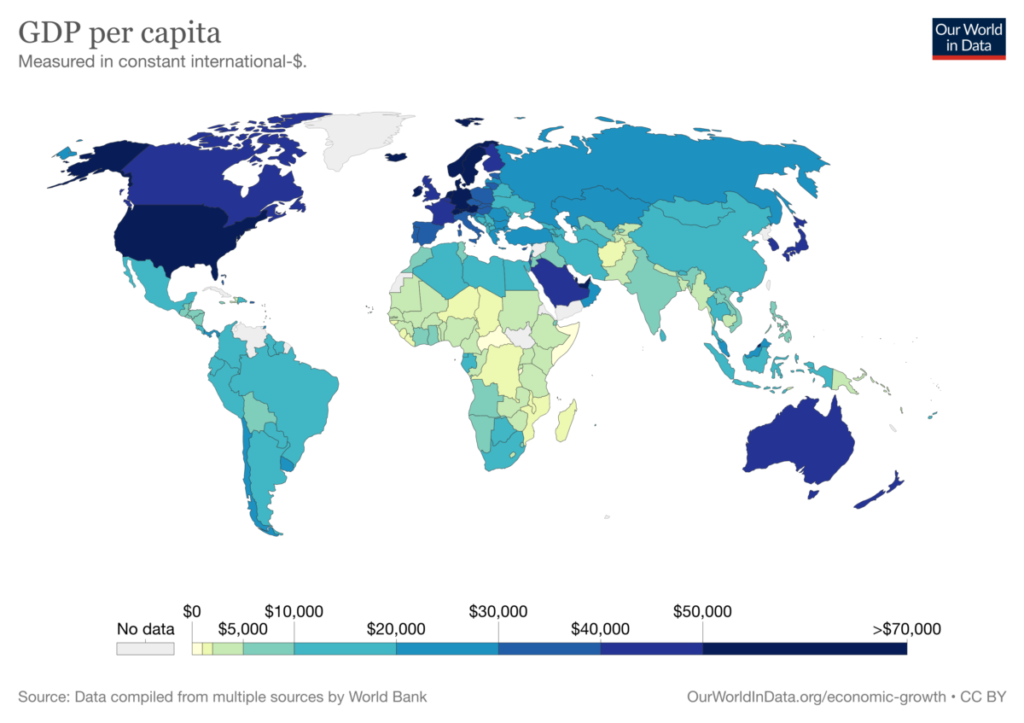

Another geographical factor that contributes to the narrower earnings gap in ski racing is the demographic breakdown of skiing itself. Unlike other globally popular games like soccer, tennis, or basketball, which do not require expensive equipment or field access, skiing is very expensive to learn and even more expensive to compete in. On top of this, skiing requires access to mountainous areas with proper weather conditions that are not easy for many to find. In fact, it is next to impossible for some nations to adequately offer skiing given their local climate. When one seeks to overlap the Venn diagrams of overall gender equity with regions that have access to ski resorts, it becomes quite evident that skiing is in the center of the overlap. As the charts reflect, these locations mostly include countries falling in the northern and central part of Europe as well as North America and Canada. As a consequence, skiing has a strong underpinning of a sport well primed for strong gender pay equity among its male and female participants.

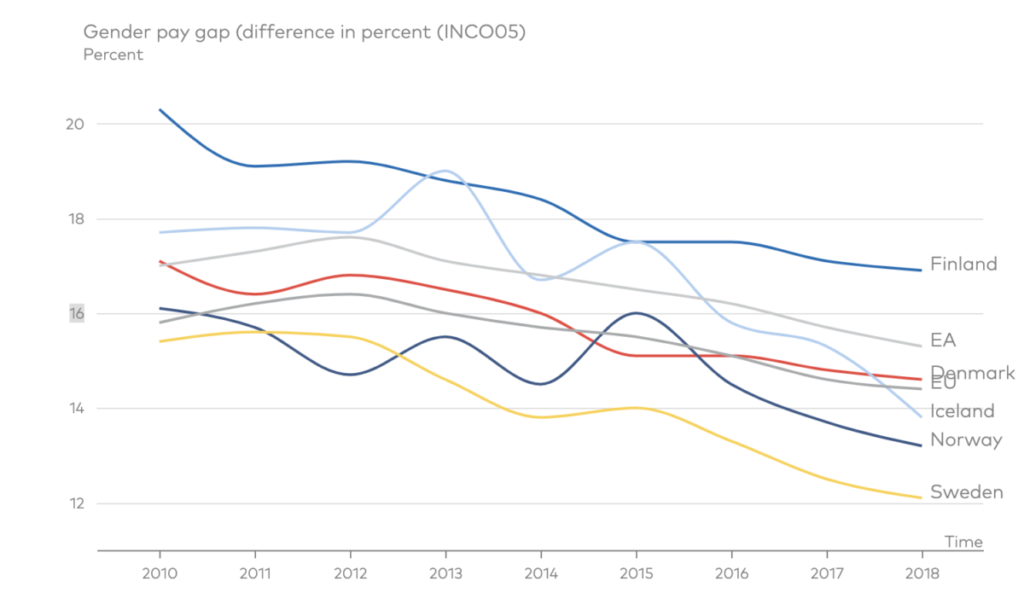

There is no question that females in sports played predominantly in countries with lower degrees of gender inequity fare far better economically than females in sports elsewhere and skiing is clearly no exception. Correspondingly, it is within the borders of Northern and Central Europe, North America, and Canada- the biggest hubs for skiing- where gender inclusivity is at the nexus of everyday life. In these countries, females have a greater degree of mobility and opportunity in the realms of security, inclusion, and justice. For instance, the Nordic region, home to four of the top five scorers out of the 144 countries in the World Economic Forum’s annual Global Gender Gap Report have the highest workforce participation rates in the world- an impressive statistic that can be attributed to various family-friendly policies introduced to their countries over the past few decades. Some of these policies include fines for companies with gender wage gaps (Iceland), paid mandatory parental leave (Norway), flexible schedules (Finland and Sweden), and partially subsidized and affordable childcare (Denmark). The payoff for these federal measures has been phenomenal. As evidenced by the graph below, over the past decade, the overall gender wage cap has decreased dramatically in these countries. This makes sense. If both parents are mandated to take time off, childbirth discrimination in the workforce can be mitigated. By the same token, with subsidized and/or affordable childcare in conjunction with more flexible work schedules, single mothers can find precious time to advance their careers rather than primarily focusing on their children’s needs. And those areas with wage cap penalties make a more gender balanced workforce not only incentivized but also ethical. Interestingly, according to an OECD report, with these policies in place, GDP per capita has increased by 10% to 20% over the past 40 to 50 years in countries making the effort. Beyond their monetary benefit, these measures have prompted a major shift in culture within these nordic regions- one that may have seemed inconceivable only a few decades prior. With Nordic countries offering many of the world’s available skiing destinations, there is no question that this newfound culture of gender inclusivity, in turn, makes the sport of ski racing more inclusive in itself. While central Europe, North America, and Canada are years behind compared to their Nordic counterparts, these countries continue to make significant strides towards a more gender equal world. Such countries have introduced various gender equity measures to be met by its citizens, promoted more females in visibly significant positions of power, and encouraged a media culture where females are deemed significant. Moreover, such areas are considered some of the most well developed regions around the globe. Unlike many second and tertiary world countries where female empowerment is not prioritized, individuals who populate these regions have significantly more time, resources, civil freedoms, and access to sports than elsewhere. Put simply, these measures have successfully promoted cultures where gender equity is no longer a standard to strive for but a cultural benchmark for generations to come. Thus, there is no question that much of the success of females in the sport of skiing can be attributed to the unique demographic breakdown and gender opportunity available at the field of play.

The Correlation with Sovereign Wealth

The relationship between skiing’s popularity and the caliber of gender equity inhibiting those regions does not exist in isolation. Yet another causal factor is the level of gender pay equity is the correlation with the field of play and sovereign wealth. The Western countries referenced above where skiing is most popular, are not only countries with lower wage gaps, but also countries that are more wealthy in general.

This graph, depicting 2017 per capita GDP, inversely mirrors the Gender Inequality Index from above, with the countries with higher GDP per capita (Northern & Western Europe, Canada & the US, etc.) being the same countries where Gender Inequality was relatively low. With GDP per capita being the standard measure of wealth, prosperity, and quality of life, it is fair to discern from these maps that there is an extremely strong correlation between the wealth & development of a country and that country’s policies, customs, and beliefs towards women and gender equality. Given that skiing not only requires money (for equipment, travel, housing, etc.), but also exists mostly in countries with the highest GDP per capita, there is no doubt that high levels of sovereign wealth is a key causal factor in the nature of skiing and its low gender wage pay gap. Richer countries in general cultivate greater opportunities and lower impediments for its female population to have access to and thrive in the sport.

The Graceful Nature of the Sport

Yet another reason as to why females in skiing have fared better economically than females in other sports is the grace factor. Unlike other sports which require a great deal of physical prowess or roughness, skiing is highly graceful in nature. Rather than engaging in physical assertion to score a goal or attack a rival competitor, ski racing requires little outward aggression that the spectator can see. While females are prompted to fight in direct opposition against a rival for a ball or a point as they do in other sports, in skiing, the outward intensity is entirely concealed within one’s own gear- gear that looks the same irrespective of gender. Perhaps this mere attribute helps drive pay similarity. At the same time, skiing is an individual speed sport where the rival is the clock. Generally, spectators love to watch the aerodynamic competitor gracefully eclipse speed barriers. Meantime, the snow, the vistas and the pure splendor of the fields of play only add to the gracefulness factor.

The grace component of alpine racing and skiing as a whole has been a topic of discussion ever since the inception of the sport. Originally, the females were introduced to the sport of ski racing on the basis of its physical beauty. In 1923, an all ladies club was founded by Arnold Lunn at the Palace Hotel in Mürren Switzerland to encourage alpine racing for women. While Lunn pioneered The Alpine Ski Club in 1908 to promote ski racing in Europe, he denied membership from women. Years later, Lunn came to the realization that skiing was not only a feasible sport for females but an attractive one, and he thus started the Ladies Ski Club shortly after. The club served as one of the first ski racing organizations to ever welcome women. After its advent, the all-female Schweizerischer Damen Skiklub was founded across the valley. Both clubs trained young women in the sport of alpine ski racing and enjoyed a friendly rivalry where the two teams would compete against each other throughout the winter. If it was not for Lunn’s creation of the Ladies Ski Club, an initiative that was originally prompted solely on the basis of beauty and grace, the history of females in skiing and their pay equity might have been different. But that early competition combined with the graceful beauty of just about every aspect of a highly competitive speed sport where men and women have the same androgynous appearance in their equipment has certainly helped.

Where do we Go From Here?

In a world that is evolving faster than ever, some problems seem to keep coming back. One of them is the wage gap between males and females. Although wages are nearing closer to each other by the day overall, in the world of athletics they certainly aren’t. In fact, there is a substantial difference in pay between genders that needs to be addressed. While the issue is complex, the bottom line is simple: all professional athletes, male or female, deserve to be paid equally for their hard work and time. While there is a vast pay gap between genders in the sports world, professional skiing is arguably quite equitable. There are numerous reasons for this including socioeconomic, religious, and cultural factors. By dissection the ski industry, a solution to the overall problem of gender inequality in all sports, might become more evident.

With that, skiing is fortunate. From a pay equity standpoint, it enjoys great prominence. What does it imply for other sports? To answer this, it is important to analyze some key statistics across all sports to find out what needs to be done to keep shrinking the wage gap. The first step in closing the gap is to ensure women and men are being treated fairly by their respective organizations and leagues. In a sport like women’s basketball, the revenue generated is significantly less than that of the men, so the leagues can not afford to pay the athletes equally. This is a problem which is hard to tackle but the bigger problem is that women may also be making proportionally less money within their sport. For example, recently in the National Basketball Association, the men’s league earned approximately $5.9 billion dollars compared to the $51.5 million that the Women’s National Basketball Association generated. It would make sense that the athletes in the women’s league would be paid less, but another statistic is very important. Of the $5.9 billion made in the NBA, 50 percent of it was earned by the players. Alternatively, in the WNBA only 23 percent of the total earnings went to the players. This phenomenon is prevalent in many sports and is a big problem in perpetuating the pay gap. Luckily skiing is different. Both women and men in skiing garner relatively equal payouts for their participation. That is because both gender groups generate similar levels of revenue and the revenue is largely driven by individual successes of the participants. Lindsey Vonn referenced this when she said that if you are not a top 10 skier, male or female, it is extremely difficult to make a living. She was clear in not differentiating among gender. That is the nature of an individual sport. The top athletes will be paid similarly but many others will struggle. In the world of elite skiing, men and women are paid the same amount by the hosts of the tournaments, but men can sometimes make more money off endorsements than women. The point here is that men and women are at least paid the same amount for the same job in their competitions. Issues such as these ones contribute to the widening of the gap in many sports. Once issues like the 23 percent to 50 percent payout in basketball are addressed, focus can be placed on how to balance endorsements and other external compensation to further drive fairness and narrow the gap. To do so, it is ultimately important for sport teams, athletic organizations, and the media to try and balance viewership and exposure of their star participants. That is when the pay gap for sports in general will shrink and more closely resemble that of the ski racing world.

Conclusion

Gender pay inequality in sports has been a long-standing challenge. Across nearly all occupations, women have historically earned far less pay than men. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, women earn 82 cents for every dollar men earn. Even more concerning, given the influx of layoffs and lack of child support induced by the recent COVID-19 pandemic, some demographers estimate that female labor force participation has recently been set back by approximately 30 years. With many believing that the pandemic has only accelerated deep-rooted labor trends, this result is not surprising. The same can be postulated for sports. Pre-Covid, wage gap issues were pervasive. In fact, one need not look farther than the recent dispute with the US Women’s World Cup soccer team vis-a-vis their male counterparts. Despite winning four of the last eight World Cups, the US women have enjoyed significantly less pay than their US male counterparts, who have never even won the tournament. In the realm of sports, the male-female wage gap has almost always been a challenge to overcome.

Interestingly, women’s downhill ski racing is the exception. The gender gap in the sport of ski racing is narrow. And compared to other sports, it was never that large to begin with. In fact, according to FIS, for the past three years, the top female alpine racers have consistently out-earned their male counterparts. While much of this success can be attributed to a range of causal factors including the individual nature of competition, the geographic field of play, the sport’s correlation with sovereign wealth, and the graceful nature of the sport, the facts still speak for themselves. Though many may not consider downhill ski racing as one of the leading sports of the world, there is much the sport can be proud of. In considering gender pay equity, skiing is the winner and the example all can look towards, hands down.

Works Cited

5 Facts About the State of the Gender Pay Gap, blog.dol.gov/2021/03/19/5-facts about-the-state-of-the-gender-pay gap#:~:text=Women%20earn%2082%20cents%20for,for%20many%20women%20of %20color.

“A 94-Year History Of Team USA Women At The Winter Olympics.” Team USA, www.teamusa.org/News/2018/March/30/A-94-Year-History-Of-Team-USA Women-At-The-Winter-Olympics.

“About Lindsey Vonn.” Lindsey Vonn, www.lindseyvonn.com/en/about-lindsey/.

Allen, E. John B. “Sierra “Ladies” on Skis in Gold Rush California.” Journal of Sport History 17, no. 3 (1990): 347-53. Accessed April 20, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/ 43609195.

Alpinestar Gate. “The Best Female Ski Racers of All Time.” Alpine Start Gate, 13 Feb. 2021, alpinestartgate.com/post/the-top-10-female-skiers-of-all-time/.

“Annemarie MOSER-PROELL.” Homepage, www.fis-ski.com/en/alpine skiing/alpine-news-multimedia/news-multimedia/athletes/article=annemarie moser-proell.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Annemarie Moser-Pröll”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 23 Mar. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Annemarie Moser-Proll. Accessed 15 May 2021.

“Closing the GENDER GAP: The 10 Best and Worst Countries for Women.” Global Citizen. Accessed August 21, 2021. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/best worst-countries-for-women-2018-list-ranking/.

Dodd, Gabby. “What It’s like for Female Skiers, Riders in a Male-Dominated Sport.” Eagle’s Eye, February 3, 2020. https://snceagleseye.com/11428/campus/what-its like-for-female-skiers-riders-in-a-male-dominated-sport/.

Fis. “Mikaela SHIFFRIN.” SHIFFRIN Mikaela – Athlete Information, www.fis ski.com/DB/general/athlete-biography.html?competitorid=164835§orcode=AL.

Fishman, Jon M. Mikaela Shiffrin. Minneapolis, MN: Lerner Publications Company, 2015.

“GDP per Capita.” Our World in Data. Accessed September 1, 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/gdp-per-capita-worldbank.

“Gender Inequality Index from the Human Development Report.” Our World in Data. Accessed September 2, 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/gender-inequality-index-from-the-human-development-report.

“Gretchen Kunigk Fraser.” U.S. Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame, 26 Nov. 2018, skihall.com/hall-of-famers/gretchen-kunigk-fraser/.

Kaplan, Emily. “U.S. Women’s Soccer Equal Pay Fight: What’s the Latest, and What’s next?” ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures, November 9, 2019. https://www.espn.com/sports/soccer/story/_/id/27175927/us-women-soccer-equal pay-fight-latest-next.

Kathleen Elk. “Olympian Lindsey Vonn: The Wage Gap in Professional Skiing Is ‘Severe’.” CNBC. CNBC, April 10, 2018. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/04/10/olympian-lindsey-vonn-the-wage-gap-in professional-skiing-is-severe.html.

Layden, Joseph. Women in Sports: The Complete Book on the World’s Greatest Female Athletes. Los Angeles, CA: General Pub. Group, 1997.

“Lindsey Vonn.” Olympics.com. Accessed August 21, 2021. https://olympics.com/en/athletes/lindsey-vonn.

“Lindsey Vonn on Trump Comments: ‘As an Athlete I Do Have a Voice’.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, 8 Dec. 2017, www.usatoday.com/story/sports/olympics/2017/12/08/vonn-happy-to-mix-sport and-politics-ahead-of-olympics/108433834/.

“Lindsey Vonn.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/biography/Lindsey-Vonn.

“Lindsey Vonn.” Team USA, www.teamusa.org/us-ski-and snowboard/athletes/lindsey-vonn.

Loring, Maggie. Skiing: A Woman’s Guide. Camden, Me: Ragged Mountain, 1999.

Megan Harrod August. “Samuels’ Experience as a Black Woman in Ski Racing.” U.S. Ski & Snowboard, usskiandsnowboard.org/news/samuels-experience-black-woman ski-racing.

“Mikaela Shiffrin.” Team USA, www.teamusa.org/us-ski-and snowboard/athletes/Mikaela-Shiffrin.

“Mikaela Shiffrin.” U.S. Ski & Snowboard, usskiandsnowboard.org/athletes/mikaela shiffrin.

“3 Women Top Alpine Skiing’s World Cup Prize Money Table — and One’s from Colorado.” The Denver Post. March 22, 2021. https://www.denverpost.com/2021/03/22/alpine-skiing-world-cup-prize-money/.

Richter, Felix. “Infographic: Where Most People Are Hitting the Slopes.” Statista Infographics, December 6, 2018. https://www.statista.com/chart/16330/average-number-of-skier-visits-per-season/.

Shinn, Peggy. World Class: The Making of the U.S. Women’s Cross-Country Ski Team. Lebanon, NH: ForeEdge, an imprint of University Press of New England, 2018.

“Skiing Phenom Mikaela Shiffrin, Inspired by Other Women Athletes, Has Found Her Voice.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 10 Mar. 2020, www.latimes.com/sports/story/2020-03-10/mikaela-shiffrin-alpine-skiing-winter olympics-slalom.

“The Future of Ski Racing Is Female.” Ski Mag, 12 Jan. 2021, www.skimag.com/news/the-future-of-ski-racing-is-female/.

“The Gender Pay Gap, Existing but Decreasing.” Nordic Statistics database, March 11, 2020. https://www.nordicstatistics.org/the-gender-pay-gap-existing-but-decreasing/.

“Top Women in Winter Sports History.” Ski Mountain View. Accessed August 7, 2021. https://skimtview.org/top-women-in-winter-sports-history/.

“Young, Gifted and Oh so Fast.” Sports Illustrated Longform. Accessed August 21, 2021. https://www.si.com/longform/sochi/shiffrin/index.html.

WBUR. “Olympian Lindsey Vonn Says Women Should Be Strong, Not Skinny.” Olympian Lindsey Vonn Says Women Should Be Strong, Not Skinny | On Point, WBUR, 20 Oct. 2016, www.wbur.org/onpoint/2016/10/20/lindsey-vonn-strong.

Williams, Peter W., and Christine Lattey. “Skiing Constraints for Women.” Journal of Travel Research 33, no. 2 (1994): 21–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759403300204.

“Women’s Ski Jumping Takes Aim Winter Olympics. History.” Women’S Ski Jumping Takes Aim Winter Olympics. History | International Skiing History Association. Accessed August 4, 2021. https://www.skiinghistory.org/history/women%E2%80%99s-ski-jumping-takes-aim winter-olympics.

“World Ski Resorts Map.” Maps of World. Accessed September 1, 2021. https://www.mapsofworld.com/world-ski-resorts.htm.

Written by Saadia Zahidi, Managing Director. “These Are the 10 Most Gender Equal Countries in the World.” World Economic Forum. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/11/these-are-the-10-most-gender-equal-countries-in-the-world/.

———. “What It’s like for Female Skiers, Riders in a Male-Dominated Sport.” Eagle’s Eye, February 3, 2020. https://snceagleseye.com/11428/campus/what-its-like-for female-skiers-riders-in-a-male-dominated-sport/.

One Reply to “What we can Learn from the Female [Trail]blazers of Alpine Skiing Since 1924 Through the Present”