Despite the increasing belief of transgender athlete domination in sports, the two most recent Olympic games, the 2020 Summer Olympic Games and the 2022 Winter Olympic Games, were the first to have openly transgender athletes compete. Even with this being a recent development, the Olympics have allowed transgender athletes to compete since the early 2000s, as long as certain criteria were met. These criteria have changed over the years since their implementation in 2003 due to the increasing activism of both transgender individuals as well as LGBT activists. These changes in criteria have allowed the Olympics to be more welcoming to not only transgender athletes but all athletes who fall outside of the boxes that the early criteria created.

The International Olympic Committee (hereafter referred to as the IOC) first began using gender verification tests in 1968 to help prevent men from competing as women. In her book Gender Verification and The Making of The Female Body In Sport: A History of The Present, Sonja Erikainen argues that this was largely due to the belief that women were weaker than men and, thus, would need some form of protection so that men wouldn’t dominate them in competition. Although gender verification testing did not come about until 1968, the Olympics’ belief in women’s supposed weaker status has been apparent since the early years of the Olympic Games. Early letters surrounding the Olympics, such as the one from Godfrey Dewey approving women speed skaters to have shorter distances, provide insight into previous policies and rules regarding women’s believed inferiority to men in sports.

The original use of gender verification was created to be used on cisgender women athletes in order to make sure that no one would have “an ‘unfair” physical advantage,” as stated by Kathryn Henne in her article “The ‘Science’ of Fair Play in Sport: Gender and the Politics of Testing,” and/or was biologically male. This early form of gender verification testing by the IOC was referred to as the “Barr Bodies” test and involved searching for cells with more than one X chromosome, which would indicate a female athlete. This type of testing became a requirement and a standard for all female Olympic athletes to undergo but was not required for male athletes. This type of testing would change a few times before it became adapted and adjusted to accommodate transgender athletes.

According to the article “Doing Gender, Determining Gender: Transgender People, Gender Panics, and the Maintenance of the Sex/Gender/Sexuality System” by Lauren Westbrook and Kristen Schilt, Transgender athletes largely went unnoticed in the national realm until 1977, which was the year that the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Dr. Renee Richards, a postoperative transgender woman, competing in the U.S. Women’s Open Tennis Tournament; however, it wasn’t until 2004 that a transgender individual could compete in the Olympics. October 2003 marks the date of the first Olympic policy regarding the participation of transgender athletes that would take effect at the following year’s Olympic Games. Prior to this, the IOC largely viewed the ability of transgender athletes to compete on an individual basis; however, this never led to any transgender athlete participation.

According to an explanatory note from IOC, this 2003 policy was “the result of an updating of the IAAF guidelines…with clear requirements…added with respect to eligibility for competition under the new gender following sex reassignment after puberty.” The IAAF, known today as World Athletics, stood for the International Amateur Athletic Federation and International Association of Athletics Federations and is an “international governing body for the sport of athletics,” as self-described on their website. In 1990, Word Athletics was the first international sports group to address transgender athletes stating that those who had transitioned, being defined as undergoing a form of sex reassignment surgery, before puberty would be allowed to compete as their preferred gender while those who transitioned after puberty would be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

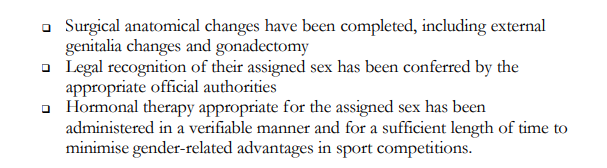

As previously stated, this idea of reviewing transgender athletes on a case-by-case basis was largely the approach that the IOC took until World Athletics, formerly known as the IAAF, updated their policies regarding transgender athletes. It was this change in policies that led the IOC to discuss what requirements would need to be met in order for a transgender athlete to compete in the Olympics. Through a meeting in Stockholm, an ad-hoc committee convened by the IOC Medical Commission came up with the following conditions for transgender participation in the Olympics:

It also states that “eligibility should begin no sooner than two years after gonadectomy,” that is removal of testes and/or ovaries, and that medical testing will be done if an athlete’s gender is questioned.

This policy remained untouched until 2012 when the IOC added a hormone criterion, which would dictate the testosterone level of those competing in the female category. The purpose of this was to make sure that the testosterone level of women athletes was not higher than what they viewed as “natural” alongside giving the IOC a way to continue to “incorporate trans and intersex athletes…without challenging the premise that modern competitive athletics rests on: the presumption that there are two genders and all athletes must be put into one of those two categories for competition,” as stated by Westbrook and Schilt. This change largely did not impact transgender athletes as much as it did cisgender athletes, as the 2003 policy for transgender participation in the Olympics already indirectly would result in the lowering of transwomen’s testosterone levels to the same levels as the average cisgender women.

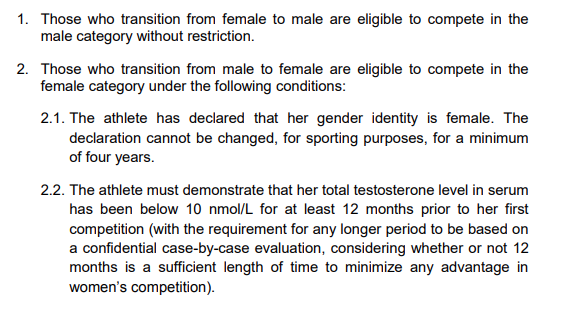

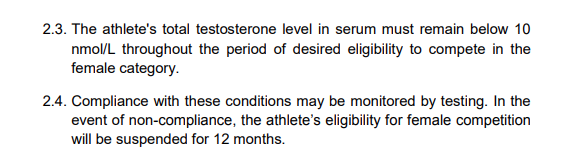

2015 would mark the year that the first official transgender policy update took place. In 2015, Kristen Worley, a transgender Canadian cyclist, sued the IOC over their requirement for transgender athletes to have to undergo a sex reassignment surgery, specifically genital reassignment surgery, to compete. She argued that those rules were in violation of her rights and were unnecessary in relation to her ability to compete. Although Worley wouldn’t officially win her case until 2017, the IOC revisited its original 2003 policy and revised it to remove the requirement of sex reassignment surgery. This new 2015 policy lists the following conditions for transgender athlete participation:

This new policy differs from the original 2003 policy in that, rather than requiring any form of sex reassignment surgery, these new criteria only require a transwoman’s testosterone levels to be within a certain range in order to participate in the Olympics. Additionally, while the 2003 policy was applicable to both transmen and transwomen athletes, this new policy completely removes all restrictions regarding transmen’s participation. The policy also states that if an athlete is “not eligible for female competition the athlete should be eligible to compete in male competition.”

This new 2015 policy is the result of two things previously discussed already: the 2012 policy update and the reoccurring belief in women’s inferiority to men in sports. Since the 2012 addition to the 2003 policy already established hormones as a valid method of determining which category an athlete is to compete in, this new updated policy only had to further define what range transgender women’s testosterone had to be in to compete. Alongside that, given that the purpose of requiring sex reassignment surgery was to lessen a transwomen’s testosterone levels, this policy does not reflect a massive change in requirements. It just deemed, due to the increase in scientific knowledge about the transgender community and transgender bodies as well as Worley’s case, sex reassignment surgery as largely unnecessary given that the same results can be achieved solely through hormone replacement therapy. What it did do, however, is demonstrate progress in terms of the IOC listening to transgender athletes.

Again, although this policy reflects listening and progress, it also reflects the belief in “female” athletes’ supposed inferiority to men. Erikainen argues that transgender men were directly stated as having no restrictions when it comes to their ability to compete in the Olympics due to those with XX chromosomes being deemed as naturally weaker and, therefore, not requiring any restrictions in order to compete against “stronger” cisgender men. According to this 2015 policy, transgender men do not even need to declare that they identify as men. It also is important to note that there is no testosterone maximum listed for transgender men who wish to compete in the men’s category.

This brings us to the most recent change in transgender policies, which was put out in 2021 just before the 2022 Winter Olympics. This policy was three years in the making and was largely created in response to the increasing number of anti-transgender individuals in sports bills being passed at lower levels of competition as argued by Britni De La Cretaz in her article “The IOC Has a New Trans-Inclusion Framework, but Is the Damage Already Done.” Given that the IOC is such a major sports organization, many lower-level sports groups look up to them and their policies when making their own decisions about things, such as the requirements for transgender athletes to compete. Additionally, De La Cretaz argues that given that there is a history of cisgender women, as well as transgender women, being deemed ineligible to compete due to their natural testosterone levels, the IOC was further motivated to pass such a policy to lessen the policing of women’s bodies in sports. Nonetheless, although the policy was created to benefit both transgender and cisgender women alike, it created many debates regarding the “unnatural advantage” that it would create in favor of transgender athletes.

This policy brought on quite a bit of controversy due to it stating that the IOC is “not in a position to issue regulations that define eligibility criteria for every sport” as well as advocating for the inclusion of transgender athlete participation. The most “controversial” points made in this new policy, which spans 6 pages and therefore cannot be discussed at length here, are regarding the eligibility of transgender women athletes to compete against cisgender women athletes without specific criteria stated. Rather than dictate exactly what requirements transgender women must meet in order to compete, the IOC has left that decision up to those in charge of various sporting systems and events. It also states that transgender athletes should be allowed to compete as their preferred gender and that they should not be assumed to have an unfair advantage over other athletes without evidence. It also states that athletes should not be forced to “undergo medically unnecessary procedures or treatment to meet eligibility criteria,” as stated in their 7th Principal regarding the “Primacy of Health and Body Autonomy.”

An important note regarding this policy is that it is NOT legally binding in any way. It doesn’t necessarily change how the Olympics will handle transgender athletes in the future and, given that this policy is quite recent, it is unknown exactly how it will impact other sporting competitions, if at all. Regardless, this new policy makes it very clear that the IOC supports its transgender athletes and recognizes that transgender women do not automatically have an advantage over their cisgender athlete counterparts. Additionally, it condemns the use of invasive examinations that have been used on both cisgender and transgender women athletes’ bodies in order to determine if they are “women enough” to compete in the female sports categories. LGBT activists stress the importance of the IOC following these new guidelines with strict implementation of the beliefs that are stated in this new policy; however, they also recognize that this policy will create a good steppingstone to battle the anti-trans sports bills that have been increasing in the recent months.

Although this 2021 policy has been well received by many individuals, to say that it has not been met with hostility by Olympic and other professional athletes would be incorrect. Veronika Stepanova, a Russian cross-country skiing Olympian, and Erik Schinegger, an Intersex skiing champion, are two individuals who were very open about their opposition to such a policy. Both of these winter athletes argue that the IOC would allow transgender women to compete against cisgender women without having to reduce their testosterone and, therefore, would lead to both men pretending to be women in order to win Olympic medals and transgender women beating cisgender women with their “unfair advantage,” that advantage being testosterone. This argument is common among those that are in opposition to this new policy, but it fails to recognize that the policy itself is, again, not legally binding and does not state how the IOC will handle future transgender Olympic athletes.

This policy has opened the door for increased participation by transgender athletes in the Olympics and other sporting competitions but also has raised questions as to how these ideas will be implemented in future Olympic games. Additionally, this new policy does not cover transgender athletes, such as the first openly nonbinary American Winter Olympic athlete Timothy LeDuc, who do not identify as either binary gender. LeDuc came out publicly as nonbinary in the year prior to the 2022 Winter Olympic Games and has since become the first transgender athlete to compete in any Winter Olympic Games. Their ability to participate has largely been a result of the increased awareness around various LGBT identities, as well as these constantly changing transgender policies. Although non-binary individuals still must compete in a very binary-sexed competition, policies such as the new 2021 IOC policy regarding transgender athletes open the door for the increased inclusion of both binary and nonbinary transgender athletes.

Bibliography

Brown, Andy. “Worley’s Case to Proceed in Human Rights Tribunal.” Sports Integrity Initiative, September 15, 2015. https://www.sportsintegrityinitiative.com/worleys-case-to-proceed-in-human-rights-tribunal/.

De La Cretaz, Britni. “The IOC Has a New Trans-Inclusion Framework, but Is the Damage Already Done?” Sports Illustrated. Sports Illustrated, March 23, 2022. https://www.si.com/olympics/2022/03/23/transgender-athletes-testosterone-policies-ioc- framework.

Dewey, Godfrey, Godfrey Dewey to Polish Olympic Committee Letter. Lake Placid Olympic Museum Archive. Lake Placid, New York. https://lpom.pastperfectonline.com/archive/776D3566-B54D-45CC-AFBF-276310542439

Dranginis, Vytautas. “Winter Olympics Ski Jump 2018.” Unsplash, March 8, 2018. https://unsplash.com/photos/hT9srFlXPGE.

Erikainen, Sonja. Gender Verification and the Making of the Female Body in Sport: A History of the Present. London, UK: Routledge, 2020. https://search.libraries.emory.edu/catalog/9937366548402486

Harper, Joanna. Sporting Gender: the History, Science, and Stories of Transgender and Intersex Athletes. London, UK: Rowman & Littlefield, 2020. https://search.libraries.emory.edu/catalog/9937286776702486

Henne, Kathryn. “The ‘Science’ of Fair Play in Sport: Gender and the Politics of Testing.” Signs 39, no. 3 (2014): 787–812. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/674208

“IOC Approves Consensus with Regard to Athletes Who Have Changed Sex – Olympic News.” International Olympic Committee. IOC, May 17, 2004. https://olympics.com/ioc/news/ioc-approves-consensus-with-regard-to-athletes-who-have-changed-sex#:~:text=The%20consensus%20is%20based%20on,and%20vice%20versa)%20in%20sport.

“IOC Consensus Meeting on Sex Reassignment and Hyperandrogenism November 2015.” stillmed.olympics.org, November 2015. https://stillmed.olympic.org/Documents/Commissions_PDFfiles/Medical_commission/2015-11_ioc_consensus_meeting_on_sex_reassignment_and_hyperandrogenism-en.pdf.

“IOC Framework on Fairness, Inclusion and Non-Discrimination On The Basis of Gender Identity and Sex Variations.” stillmed.olympics.com, 2021. https://stillmed.olympics.com/media/Documents/News/2021/11/IOC-Framework-Fairness-Inclusion-Non-discrimination-2021.pdf?_ga=2.56495211.1560876467.1642745279-1258333344.1642131641.

Lavietes, Matt. “International Olympic Committee Issues New Guidelines on Transgender Athletes.” NBCNews.com. NBCUniversal News Group, November 17, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-news/international-olympic-committee-issues-new-guidelines-transgender-athl-rcna5775.

Leidig, Michael. “Intersex Skiing Champion Say Transgender Women Should Not Compete in Female Events.” Daily Mail Online. Associated Newspapers, March 5, 2019. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-6772989/Intersex-skiing-champion-say-transgender-women-NOT-compete-female-events.html.

Ljungqvist, Arne. “Explanatory Note to the Recommendation on Sex Reassignment and Sports.” stillmed.olympics.com, April 22, 2004. https://stillmed.olympics.com/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/News/20040517-IOC-Approves-Consensus-With-Regard-To-Athletes-Who-Have-Changed-Sex/EN-report-904.pdf.

McCutcheon, Sharon. “Transgender Flag Celebrating LGBTQ Pride For June, 2019.” Unsplash, May 31, 2019. https://unsplash.com/photos/uUkjeWxSh7c.

“Russian Ski Starlet Poses Transgender Question.” RT International. Accessed April 19, 2022. https://www.rt.com/sport/541440-veronika-stepanova-transgender-skiing/.

“Statement of the Stockholm Consensus on Sex Reassignment in Sports.” stillmed.olympic.org, 2003. https://stillmed.olympic.org/Documents/Reports/EN/en_report_905.pdf.

Stryker, S. (2008). Transgender History. Seal Press, Distributed by Publishers Group West. https://search.libraries.emory.edu/catalog/990022074960302486

TEGNA, Associated Press. “Timothy Leduc Becomes 1st Openly Nonbinary US Winter Games Athlete.” KUSA.com, February 18, 2022. https://www.9news.com/article/sports/olympics/timothy-leduc-first-openly-nonbinary-us-winter-games-athlete/507-01dd1d96-bd84-4717-999f-a3d72b3a3705#:~:text=Timothy%20LeDuc%20becomes%201st%20openly,Friday%2C%20they%20made%20Olympic%20history.

Westbrook, Laurel, and Kristen Schilt. “Doing Gender, Determining Gender: Transgender People, Gender Panics, and the Maintenance of the Sex/Gender/Sexuality System.” Gender and Society 28, no. 1 (2014): 32–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43669855.

“World Athletics: About World Athletics.” worldathletics.org. Accessed April 19, 2022. https://www.worldathletics.org/about-iaaf.

Hello,

I am a student from Germany. I am currently writing an important paper on transgender athletes at the Olympic Games. Would you be open for some questions regarding this topic ?

I would very much appreciate it!

Greetings

Bela