It is no secret that skiing is an overwhelmingly white sport. Both skiers and non-skiers alike can agree that, when asked to picture the average skier, we usually conjure up images of White, wealthy, usually attractive or athletic men. While anecdotal evidence is not a sufficient replacement for actual statistics, the data that exists about skiing participation does, in fact, support this assumption.

The Demographics of Skiing Today

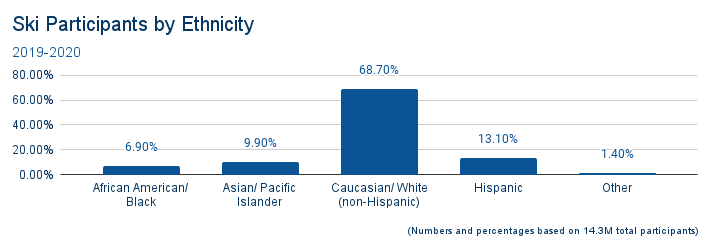

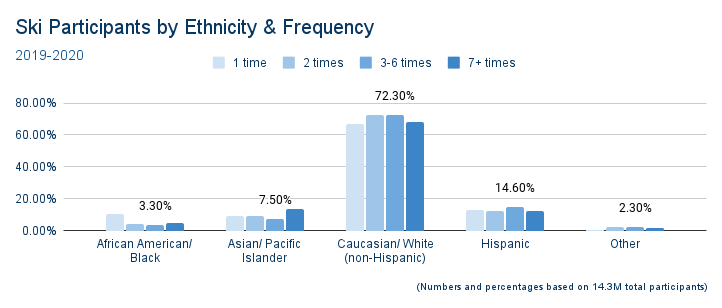

According to Snowsports Industries America, non-White skiers accounted for about one third (31.3%) of all skiers in the 2019-2020 season. Of that 31.3%, only 6.9% were Black. However, when looking at participants who skied more frequently, between three to six times a year, the number of non-White participation drops to 27.7%, of which only 3.3% were Black. On the other hand, 72.3% of skiers who ski between three to six times a year were White.

Similarly, the NSAA’s 2020-2021 demographic study shows 87.5% of U.S. downhill sports participants identify as White.

To better understand these stark racial disparities in current skiing participation, we must recognize that the prevalence of Whiteness in skiing is not a new or recent trend and, in fact, has been integral to the popularization of skiing in the U.S. by design.

Establishing a Tradition of Exclusion in America

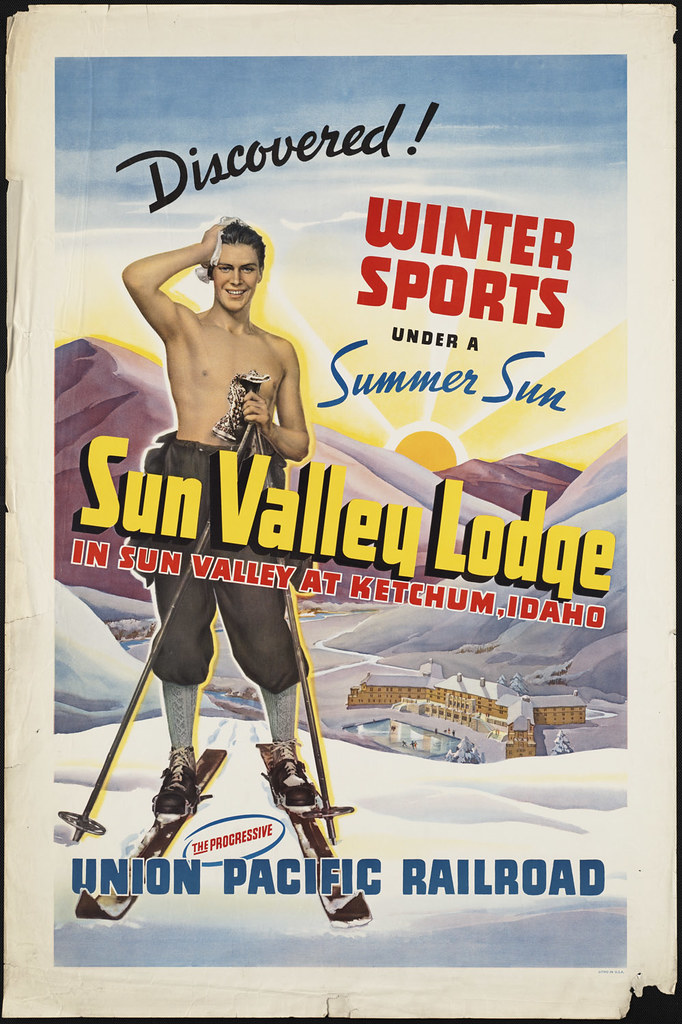

Skiing was first introduced in the United States in the 19th century by Scandinavian immigrants and was quickly adopted by residents of Western mountain towns as it provided a more functional way to get around in the winter. By the 1930s, skiing as a culture became more about fun than function, evolving from a practical means of transportation into a popular recreational activity enjoyed almost exclusively by affluent Americans who had previously experienced European ski culture on their vacations abroad. This shift, combined with an influx of European immigrants to the United States during World War II in the 1940’s, led to continued growth of ski culture through the establishment of dedicated ski clubs, races, contests, and most importantly, the purpose-built destination ski resort. The resort model was built around the burgeoning ideas that consumerism would lead to an improved standard of living and that skiing was more of a lifestyle than solely an activity. The skiing lifestyle was characterized as a cosmopolitan European way of life and had the implication of wealth, education, and worldliness. As Annie Gilbert Coleman notes in her 1996 article, “The Unbearable Whiteness of Skiing,” “the images that defined this ‘ski culture’ came wrapped in representations of ethnicity.”

As a result, ski-related businesses of all kinds used a hodge-podge of ethnically European imagery to sell and market everything from ski equipment and clothes, to hotel stays, lessons from ski instructors, dining experiences and other resort amenities. These savvy marketing ploys worked by reinforcing Whiteness and Europeanness as intrinsic to one another and enticing Americans to spend more of their expendable income on the latest ski gear trends in order to “keep up with the Joneses.”

While the culture of skiing in the United States was influenced by the Swiss, Swedish, Norwegian, Austrian, French, Italian, and German traditions in various ways, these distinctions became blurred and, as Coleman notes, “rather than emphasize specific national identities… American ski culture eventually lumped all Europeans and Scandinavians together under a lily-white ‘European’ image.” In this way, Whiteness, in itself, became synonymous with wealth, luxury, and exclusivity, such that any reference to a specific European ethnicity became superfluous. Rather than relying on Europeanness to achieve authenticity, the ski industry realized that Whiteness alone had the power to communicate status and exclusivity.

While this intentional racialization of skiing imagery, spaces, and places may be surprising to many who have not had the pleasure of studying snowsport history at length, it is a fact Black Americans have long been intimately aware of. Black people have always been made to feel as outsiders within certain sports and activities, and because of this, few scholars have looked at the historical relationship Black communities have to both outdoor spaces and leisure travel. Perry L. Carter’s “Coloured Places and Pigmented Holidays” surveys this scholarship, which includes the work of H.K. Cordell, et al. which “conclude[s] that spaces, at the very least outdoor spaces, are raced; that certain people with certain types of bodies are expected to occupy certain types of places.” Carter further asserts that “Blacks view space as raced and most spaces as White, spaces in which to be on guard. Whites view most spaces as normal (i.e. unraced), which is to say they too subconsciously perceive them as White.” This means that for the majority of Black Americans, rural spaces and the outdoors have historically been labeled as White, even if not explicitly. Anthony Kwame Harrison called this concept racial spatiality and added that in these racialized spaces, “the presence of other bodies creates social disruption, moral imbalance, and/or demands explanation.” Indeed, the few early Black skiers who attempted to break past the sport’s color line were often faced with discrimination, frequently denied stays at resorts, or confronted with outright racism on the slopes.

“Safety in Numbers”: the Emergence of Black Ski Clubs

Despite this backlash, Black skiers were nonetheless able to carve out small, but significant, spaces within the sport. By the mid 1950s, Black leisure travelers of all kinds realized that the displays of contempt and racist affronts they experienced were often mitigated by traveling in groups. For skiers, this marked the inception of all-Black ski clubs which provided more welcoming environments to engage with the sport and culture of skiing. In his The Lift Line blog, Jesse Ritner contends that these “organization[s] offered safety in numbers for Black enthusiasts who were passively or explicitly unwelcome at many resorts.”

The first of these Black ski clubs to emerge in the nation, and arguably, the world, was the Jim Dandy Ski Club, established in 1958 in Detroit, Michigan. The club began when Frank Blount, William Morgan, and Reginald Wilson decided they needed a space of their own after feeling alienated from the otherwise all-White Wayne State University Ski Club. Beginning the 1958-59 ski season with 23 members, the club quickly grew in membership after being featured in the March 1962 issue of Ebony Magazine. Stating that “club members travel as a group and are accepted at ski lodges without question,” the article and its 24 image spead depicted Jim Dandies, as members are called, carving down slopes, training with instructors, and relaxing in the ski lodge, allowing readers to see ski culture through a new lens. To quote Ritner, “the implication was if Black skiers could ski there, why not anywhere?”

In 1964, the Jim Dandies were invited to join a group of Black skiers in Denver, Colorado, leading to what their website calls the “first documented organized gathering of African-American skiers in the United States.” This meeting of between 40 to 50 skiers predated the first summit of the National Brotherhood of Skiers, one of the country’s largest Black ski organizations, by almost a decade.

Although it wasn’t the first organized gathering, The National Brotherhood of Skiers’ inaugural Summit of 1973 was nonetheless a landmark. By bringing together 13 Black ski clubs from across the nation, at least 350 skiers, it surpassed the Jim Dandies’ meeting to become the largest Black ski gathering in history. Founded by Ben Finley and Arthur “Art” Clay, the National Brotherhood of Skiers (NBS) serves as an umbrella group for Black ski clubs across the U.S. with the goal of one day placing a Black skier on the U.S. Ski Team. In its heyday, the organization was made up of upwards of 7,500 members across some 80 ski clubs. Almost 50 years after its inception, the organization continues this mission to “identify, develop and support athletes of color who will win International and Olympic winter sports competitions representing the United States and to increase participation in winter sports.” At least four NBS athletes have gone on to compete in the Olympics, including Bonnie St. John, the first African American to win a Winter Paralympics medal, winning both bronze and silver medals in 1984 in Innsbruck, Austria.

More than simply supporting their sporting interests, however, the NBS also gave Black skiers an opportunity to build a community of support that was essentially non-existent within the predominantly White sport. In an interview with the HistoryMakers Digital Archive, St. John describes her experience attending NBS summits:

I was there in Utah when they had it there in Park City, and for a week, the entire ski area turns Black. You know, ten thousand Black skiers take over the ski area. And it’s wonderful… it was like I described with the disabled skiing. It’s that I came into a world where I celebrate who I am and learn to honor my identity from other people in a way that I had never gotten before.

Of her NBS peers, she said:

…these are people able to navigate multiple worlds, find their identity, and still feel strong. So there were a lot of role models for me, in particular, Gertrude Cowan… she was such a huge role model in terms of my Black identity. And not fixing my Black identity in stereotypes, but in this courageous idea of what it means for me, and who I am, and finding a community that I could resonate with.

In a recent interview with Outside Magazine, skier Mike Lanier, who has attended the NBS Summit 22 times, noted of his first attendance in 1985, “it was like coming out of the desert into an oasis. You’re so used to being around White people. Almost nobody on the ski slopes looks like you.”

But, Are Black Ski Clubs Enough?

It is clear that Black ski clubs open the doors to skiing and snowsports to its members, but since their emergence roughly 60 years ago, the numbers have not increased much. Only 1.5% of downhill snowsports participants across the country identified as Black or African American in 2020-2021 according to the NSAA. Harrison argues that, ”despite African American inroads into skiing… their parallel integration has, in effect, contributed to the ghettoization of Black skiing into realms of non-visibility and/or extraordinariness, whereas skiing on the whole has remained remarkably and pristinely White.” While they do create spaces where more Black Americans feel comfortable skiing, Black ski clubs have not been able to significantly challenge the hegemonic Whiteness of the industry. They do not address what Coleman, and many since her, have identified as the main factors most strongly affecting Black participation in skiing: economic barriers and a pervasive lack of adequate representation within snowsports generally. Writing for Ski Magazine in 2021, Erin Key, an amateur skier from Missouri, echoes Coleman in saying, “when I’m asked why more Black people don’t ski, two thoughts come to mind: barriers to entry and representation.”

In terms of representation, visual artist Lamont Joseph White’s work has been significant. His 2020 project titled “Skiing in Color ” is a collection of paintings depicting Black skiers, snowboarders, and snowsport enthusiasts that seeks to make Blackness more visible in the snowsports industry. A snowboarder himself, White understood how important the simple act of seeing someone like himself represented in ski-themed art could be for changing perceptions of who does and does not ski. Speaking with Khai Johannes in an interview, White shared that, through his artwork, he hopes “to increase the presence of Black and brown people in the mountains. The power of representation, which brings inclusion, which then can bring opportunity — so then we’re all lifted up.” Increased representation alone, however, is also not the answer. To quote Garrett Schlag writing for Powder Magazine, to simply call for more Black participation in skiing without “altering the social environment of the mountain… will only increase the number of BIPOC subjected to racial trauma.”

Interestingly, Carter’s analysis of race and leisure literature shows that a third, more salient theory has emerged recently. It suggests that “what actually constrains African-Americans in their pursuit of leisure is a legacy of past racial discrimination and anxieties about encountering contemporary racism,” not economic barriers or representation. This legacy has been upheld by the entire outdoors sport and leisure industry, not just skiing. As such, the only way to truly address this systemic issue is through systemic changes.

A New Generation of Digital Advocacy

Discussions about race and access in skiing have existed for years, even decades, but did not often affect the larger ski industry or culture. This, however, has been changing in recent years, largely due to the surge in social justice activism targeting anti-Black discrimination across the country that began in 2013 with the Black Lives Matter movement. In 2020, the high-profile murders of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, along with several others, again galvanized racial injustice protests and created a landscape of social, cultural, and political unrest across the country. This time, the skiing industry would not be unaffected.

In response to Floyd’s murder, Vail Resorts’ CEO Robert Katz wrote an open letter calling for a reckoning of the often ignored, but nonetheless pervasive, racism throughout the ski industry. In May 2020, environmental activist, drag queen, and co-founder of The Outdoorist Oath, Pattie Gonia (@pattiegonia) collaborated with several BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) outdoors advocates to produce and disseminate a digital guide calling for increased recognition of racist practices in the outdoors industry, commitment to action and change, and allyship. Their guide was later shared by ski apparel brand Ski The East to its 176,000 Instagram followers. In June 2020, an Instagram account called Skiing is Racist (@skiingisracist) began to crowdsource and share skiers’ and snowboarders’ stories and experiences of racism, along with various related educational resources, petitions, and news articles. Similar accounts including Ski and Ride Anti-Racist Vermont (@skiantiracistvt) and Intersectional Environmentalist (@intersectionalenvironmentalist) were also created around this time.

The mere existence of these accounts shows that the push for a diversified sport and industry clearly exists, but it is also met with much resistance from the larger ski community. Scrolling through the comments on these social media pages shows how often the experiences of Black skiers are trivialized or ignored altogether. Among the more negative reactions are claims of reverse racism, insults, denying the existence of White supremacy and racism, and concern for how far the issue will go. One user rhetorically asked, “If POC choose to not go to parks, the parks are racist! What’s next, the trees are racist?” Despite the efforts of these activists, it is clear that more work must be done to engage the average skier on the importance of racial justice work. The question that persists, however, is who should that work fall on? Such a daunting task will require effort from every facet of the industry, including resort owners, equipment and apparel manufacturers and retailers, instructors, professional athletes, and average American skiers themselves.

Conclusion

Just as skiing’s history and current culture in the U.S. is inextricably linked to American racial dynamics, so too is its future. Because Whiteness has never been simply incidental to skiing culture, skiing will never become less White “over time” or without intention. To truly ameliorate access for people of color to skiing (and to other sports and outdoor activities), we have to ask ourselves the perhaps overwhelming but necessary question of why weaponizing Whiteness continues to be such a successful and profitable tool for individuals, corporations, and governments alike. The task of dismantling racism is not an easy one, but it is necessary to ensure that skiing as a sport and industry is truly representative of all skiers.

Bibliography

“About.” Lamont Joseph White. Last modified 2022. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://lamontjosephwhite.com/pages/about.

Carter, Perry L. “Coloured Places and Pigmented Holidays: Racialized Leisure Travel.” Tourism Geographies 10, no. 3 (July 28, 2008): 265–284. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680802236287.

Cole, Harriette, and Bonnie St. John. “Bonnie St. John Talks about the National Brotherhood of Skiers.” Other. The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. The HistoryMakers, August 11, 2016. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://da-thehistorymakers-org.proxy.library.emory.edu/story/521611.

Coleman, Annie Gilbert. “The Unbearable Whiteness of Skiing.” Pacific Historical Review 65, no. 4 (November 1996): 583–614. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3640297.

Cowan, Jay. “A Sport Once White.” International Skiing History Association. The International Skiing History Association, August 7, 2018. Last modified August 7, 2018. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://skiinghistory.org/news/sport-once-white.

Daddio, Jess. “REI Presents: Brotherhood of Skiing.” Uncommon Path . REI Co-op, January 17, 2019. Last modified January 17, 2019. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.rei.com/blog/snowsports/rei-presents-brotherhood-of-skiing.

“Detroit Ski Addicts: Jim Dandy Club Pursues Sport Once Ignored by Most Negros.” Ebony, March 1962. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://books.google.com/books?id=RNcDAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PA21&pg=PA21#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Donahue, Bill. “An Oral History of the National Brotherhood of Skiers.” Outside Online. Outside, January 5, 2021. Last modified January 5, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-adventure/snow-sports/national-brotherhood-skiers-oral-history/.

Finney, Carolyn. “Jungle Fever.” Essay. In Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors, 32–50. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Gordon, Jacinta. “Diversify Your Feed: Discovering Underrepresented Riders.” Coalition Snow. Coalition Snow, November 1, 2021. Last modified November 1, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.coalitionsnow.com/blogs/shoptalk/diversify-your-feed-scrolling-the-underrepresented-in-snow-sports.

Harrison, Anthony Kwame. “Black Skiing, Everyday Racism, and the Racial Spatiality of Whiteness.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 37, no. 4 (2013): 315–339.

“History.” Jim Dandy Ski Club. Jim Dandy Ski Club, 2022. Last modified 2022. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.jimdandyskiclub.com/info.php?pnum=759b83247ad63a.

Intersectional Environmentalist (@intersectionalenvironmentalist). 2020. “Coming soon. A platform for resources, information and action steps to support intersectional environmentalism and dismantle systems of oppression in the environ…” Instagram photo, June 8, 2020. https://www.instagram.com/p/CBMtSsNhIi9/.

Jag, Julie. “‘We Love the Mountains. The Only Difference Is the Color of Skin.’ Utah, U.S. Ski Resorts Coming to Grips with Their Lack of Diversity.” The Salt Lake Tribune. The Salt Lake Tribune, January 22, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.sltrib.com/sports/2021/01/22/we-love-mountains-only/.

Johannes, Khai. “Meet the Park City Artist Who Brings Black Heroes to the Mountain.” Visit Utah. Utah Office of Tourism, n.d. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.visitutah.com/articles/meet-the-park-city-artist-who-brings-black-heroes.

Johnson, Jiquanda. “There Are Very Few Black People Who Ski. The Oldest Black Ski Club in the Nation Is Working to Change That.” Black Like Us. Meta Bulletin, February 28, 2022. Last modified February 28, 2022. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://blacklikeus.bulletin.com/there-are-very-few-black-people-who-ski-the-oldest-black-ski-club-in-the-nation-is-working-to-change-that/.

Kahl, Rick. “Snowsports Statistics in Black and White.” International Skiing History Association. The International Skiing History Association, 2019. Last modified 2019. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.skiinghistory.org/snowsports-statistics-black-and-white.

Kelly, Tom. “Lamont Joseph White: Skiing in Color.” Ski Utah. Last modified January 20, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.skiutah.com/blog/authors/tom-kelly/lamont-joseph-white-skiing-in-color.

Key, Erin. “How Skiing’s Whiteness Has Affected Me, and How We Can Change It.” Ski. Outside, February 19, 2021. Last modified February 19, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.skimag.com/culture/making-skiing-more-diverse/.

Mills, James Edward. “Opinion: The Outdoor Industry Still Can’t Get DEI Right.” Outside Business Journal. Last modified September 1, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.outsidebusinessjournal.com/issues/diversity-equity-inclusion/opinion-the-outdoor-industry-still-cant-get-dei-right/.

“Our Story.” NBS.org. National Brotherhood of Skiers, Inc., 2022. Last modified 2022. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.nbs.org/content.aspx?page_id=22&club_id=681344&module_id=479193.

Pattie Gonia (@pattiegonia). 2020. “WHITENESS IN THE OUTDOORS. I’ve had this idea in my head for a while now and the recent events in the news, specifically the murder of Ahmaud Arbery, a black man…” Instagram photo, May 13, 2020. https://www.instagram.com/p/CAImIQCp5nb/.

Rep. SIA Participation Study 2019-2020. Snowsports Industries America, April 28, 2021. Accessed April 27, 2022. https://industry.traveloregon.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/SIA_Participation_Study_2019-2020_Nov.pdf.

Ritner, Jesse. “An Incomplete History of Black Skiers.” Web log. The Lift Line. WordPress, May 10, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://the-lift-line.com/2021/05/10/an-incomplete-history-of-black-skiers/.

“U.S. Downhill Snowsports Participant Demographics .” NSAA. National Ski Areas Association, December 2021. Last modified December 2021. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://nsaa.org/webdocs/Media_Public/IndustryStats/Skier_Demographics_2021.pdf.

Schlag, Garrett. “No, Skiing Isn’t a Welcome Place for People of Color- Not Yet.” POWDER. Powder Magazine, August 18, 2020. Last modified August 18, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.powder.com/stories/no-skiing-isnt-a-welcome-place-for-people-of-color-yet/.

Ski and Ride Antiracist VT (@skiantiracistvt). 2020.”We are skiers and riders who are committed to holding Vermont ski resorts accountable for engaging authentically in the fight for racial justice. Our message is…” Instagram photo, June 10, 2020. https://www.instagram.com/p/CBQkngtHUrD/.

Skiing is Racist (@skiingisracist). 2020. “Welcome. Skiing has been exclusionary since it’s inception. We started this account after seeing many like it in different industries. Feel free to dm or email…” Instagram photo, June 26, 2020. https://www.instagram.com/p/CB51JOvp3wK/.

Williams, Kaya. “A Founding Generation of Black Skiers Looks Back and Forward to Expand the Sport.” Snowmass Sun. The Aspen Times, February 9, 2022. Last modified February 9, 2022. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.aspentimes.com/news/a-founding-generation-of-black-skiers-looks-back-and-forward-to-expand-the-sport/.

13 Replies to “White as Snow: An Examination of Race within Skiing”