Dogs have played a part in Alaskan life for centuries, dating back at least 500 years if not more. One of the most notable ways in which indigenous Alaskans interacted with their dogs was through the dogsled, which for centuries served as the primary, if not only, method of traversing the cold arctic terrain. This reliance on sled dogs made them a critical part of Native Alaskan society even into the 19th and early 20th centuries, as sled dogs are depicted in early Inuit interactions with outside settlers in the 1800s. Most famously, they were utilized in the 1925 sled run to Nome, a dogsled relay to deliver medicine during a diphtheria outbreak.

However, as the 20th century progressed, the traditional sled dog became less common as a form of transportation, giving way to mechanized vehicles and more modern technologies. While these new developments offered meaningful improvements in transportation, they would also phase out a cherished Alaskan tradition with a rich, storied history.

In the 1960s and 70s, a group of Native Alaskans, concerned that the dogsledding tradition and its role in Alaskan history would fade out of public memory, devised a way to revive the practice in the modern age. So was born the Iditarod, a dogsled race across the famous Iditarod Trail. The founders hoped that the race would allow them to keep in touch with the traditional Alaskan spirit and their roots. But how would dogsledding survive against the technological and capitalist forces that caused its initial decline? And how could it do so in a way that maintained the true traditional spirit of the practice and preserved the premodern culture?

Origins of Dogsledding in Alaska

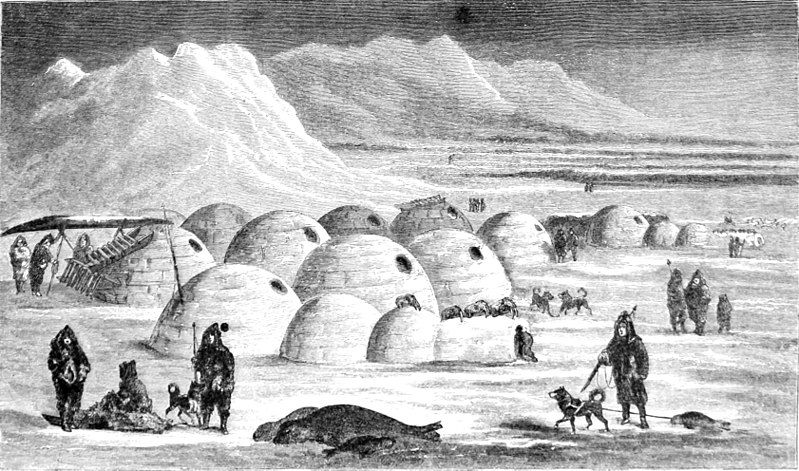

Though there is not a clear consensus dating the true origins of dogsledding in North America, dogs played a critical part in Indigenous Alaskan society. According to a report from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, archeological evidence suggests that Indigenous peoples along the Alaskan coast kept dogs several thousand years ago, and the practice of using dogs to pull sleds arose in Alaska at least 500 years ago. By the time European explorers established contact with the Inuit people in the mid-19th century, keeping dogs and the practice of dogsledding had become a visible part of native Alaskan identity. In the early 1860s, American explorer Charles Francis Hall chronicled an Arctic expedition in his narrative Life with the Esquimaux. In one passage, he writes that upon approaching “a complete Esquimaux village, all the inhabitants, men, women, children, and dogs, rushed out to meet [him].” This inclusion of dogs in the characterization of a “complete” village portrays the central role that the dogs played in the Native villages. Later in the book, he goes on to note some of the ways that dogs and dogsledding were used, writing that dogs were brought along on trips to hunt seals, and noting the use of sled dogs to transport food and supplies across the terrain.

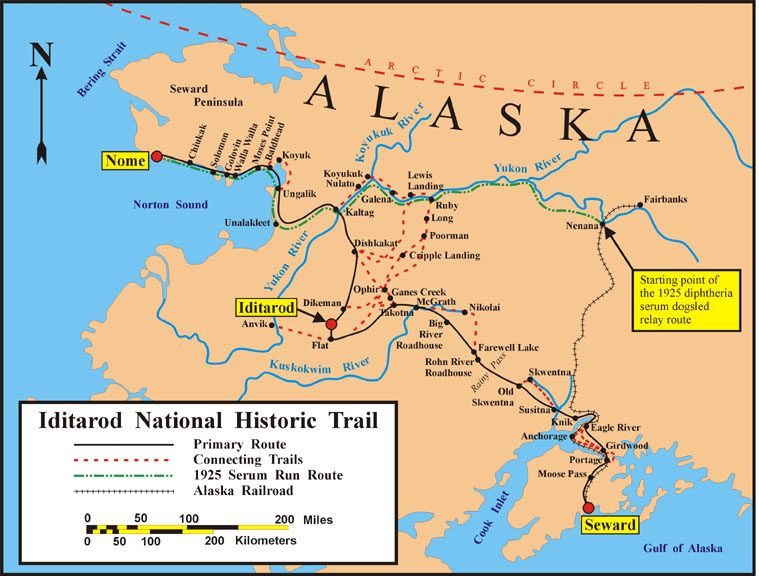

Dog teams were frequently used by Indigenous Inuit peoples for hunting, and sledding became the premier form of land transportation. The reports of Russian explorer Lt. Lavrentii Zagoskin note that the Native people utilized a well-established network of dogsled trails to traverse the icy Arctic terrain. As American settlements came to Alaska in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the use of the sled dog would only increase in prominence. Sled dogs were able to cross areas that were not accessible to automobiles at the time, so dogsled use remained the only way to transport people and equipment across Alaska. Sled dogs would become the basis of the mail service and various supply chains, crossing the expansive Alaskan trail network. The predominant dogsled trail was known as the Iditarod Trail. Spanning across Alaska, from Nome on the West Coast to Seward in the Alaskan Gulf, the Iditarod would be the primary dogsled thoroughfare through Alaska.

For centuries, dogsledding was unrivaled in its relatively low cost, reliability, and ability to cross terrain that was inaccessible by any other method. However, modern technology would soon challenge its dominance as a mode of transportation and diminish the prominence of this staple of Indigenous life.

“Decline of the Dogsled”

In the mid 20th century, developments in technology would provide a more modern alternative to the sled dog, specifically in the form of the mechanized toboggan. This new technology was faster than the traditional dogsled, and offered considerable advantages in terms of maintenance and safety. These advantages were quickly realized among Alaskans, and the decline of the dogsled in favor of the mechanized toboggan would become immediately apparent through in the 1960s. In 1968, a study by Karl E. Francis sent out a questionnaire to residents of 27 villages in northern, western, and interior Alaskan villages asking for details on the use of dogsleds and mechanized toboggans between 1963 and 1968. (Francis does not specify the ethnic demographics of the respondents; however, he notes that the population of the responding villages covered most of the population of arctic Alaska at the time. To get some insight into the demographics of the respondents, we can look to a report from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game studying demographic trends. The oldest available report on the ethnic breakdown of rural Alaskans is from 2000, roughly 30 years after Francis’ study; this report notes that 54% of rural Alaska residents identify as Alaska Natives. While the reports are not exactly from the same time period, we can hypothesize that Alaskan villages of the late 1960s contained a significant Alaska Native population.)

While some questionnaire respondents signaled an affinity for the traditional mode of transportation, and the mechanized toboggan posed some shortcomings with regard to cost concerns and mechanical failures, the shift towards the more modern technology was clear. Across the five-year period from 1963 to 1968, the number of mechanized toboggans in use increased fivefold, from 187 to 974. Meanwhile, across that same period, the number of active dogsled teams decreased from 726 to 420, a roughly 42% decrease.

Given that a sizeable fraction of the respondents were likely Alaska Natives, this shift away from the traditional practice comes with greater implications regarding the decline of indigenous customs. In addition to causing the contributions of generations of Alaska Natives to fade from memory, the replacement of tradition with technology also poses serious and immediate practical concerns. Just as the mechanized toboggan challenged the status of the dogsled, a similar phenomenon occurred slightly later in the 20th century with the invention of the GPS leading to a loss of traditional Inuit navigational practices. A paper by Dr. Claudio Aporta of Dalhousie University and Dr. Eric Higgs of the University of Victoria study how the adoption of GPS as the primary guider of navigation caused a decline in proper understanding of the geography and environment, as that knowledge is acquired by learning the traditional Inuit wayfinding methods. Aporta and Higgs assert that, while the GPS can provide assistance when navigating, it is unable to actually provide and pass on knowledge to the user. They write that “many younger people do not have the depth of knowledge to move about safely,” and many older Inuit blame the modern GPS technology for eroding that historic knowledge among the new generation. Francis also supports this belief, noting that despite the speed and economic advantages of the mechanized toboggan, “there is considerable evidence that the famed Eskimo skill for finding his way home in a storm is not nearly so effective without dogs,” once again indicating the tendency of technology to reduce traditional skills and knowledge.

Both authors also express concerns about the reliability of modern technology, noting that electronic parts are sometimes prone to failure, especially in the cold Alaskan winters. By contrast, traditional practices come with centuries of proof of reliability. In the event of mechanical failure, it is critical that knowledge of the traditional practices is not lost, as they may be the only hope for a stranded navigator.

Reviving the Practice

In the mid-to-late 1960s, a committee of Alaskans was tasked with scheduling events to commemorate the upcoming 1967 celebration of Alaska’s centennial year being a part of the United States. Among this group was Dorothy Page, who would come to be known later as the “Mother of the Iditarod.” Although Page was not an Alaska Native, having spent most of her early life elsewhere in the United States before moving to Alaska in 1960, she became very involved with Alaskan public service projects, and was dedicated to preserving Alaskan history and tradition. Page felt that the decline in the prominence of dogsledding had caused many Alaskans to lose touch with this historic practice, even to the extent of forgetting about its existence and prominent role in Alaskan history. She proposed “a spectacular dog race to wake Alaskans up to what mushers and their dogs had done for Alaska,” placing the practice back into the public eye. She reached out to dog musher Joe Redington, Sr., a veteran of World War II, who moved to Alaska in 1948 and took up competitive sled dog racing. Although neither Page nor Redington was an Alaska native, they both shared a passion for preserving the traditional indigenous custom of dogsledding, and the two of them would collaborate to organize the first Iditarod race. The first two races, in 1967 and 1969, were held along a short subsection of the trail, a nine mile stretch from Knik to Big Lake. However, in 1973, the race would expand to cover the full Iditarod trail, as racers traversed 1,000 miles of Alaskan wilderness and revived the classic mode of trans-Alaskan travel, in a race that is replicated each year to this day.

Iditarod in the 21st Century

For the last 50 years, the Iditarod race has functioned as a way for Alaskans to connect with the storied tradition of dogsled racing, and has gained international attention, viewers from around the world. In addition, the population of dog mushers who participate in the competition has branched out globally as well, including not just indigenous Alaskans and other Alaska residents, but also competitors from elsewhere in the United States and occasionally even abroad.

To understand how the Iditarod has maintained its popularity, we can explore the motivations of the tourists who visit Alaska to witness it. While it may seem like these tourists are simply traveling to view a sporting event, many of them are in fact driven by forces of cultural tourism and “salvage tourism”, traveling to experience facets of native and indigenous culture.

When viewing the Iditarod through the lens of salvage tourism, find it to be a foundational principle of the race’s founding. In Staging Indigeneity, Katrina M. Phillips writes that “salvage tourism is explicitly tied up in trying to salvage American Indian cultures before Indians, in the minds of non-Natives, die off, change, or degenerate from their ideals of a pristine Indian past,” a sentiment that echoes strongly in the story of Page and Redington founding the Iditarod. Neither of the founders were Alaska natives, but they felt that Alaskans, even indigenous people, had forgotten the dogsledding tradition, and they sought to “salvage” the custom. The transformation of dogsledding from a standard means of transportation into the spectacle of a sporting competition reflects another principle of salvage tourism, which is that “It requires transformation and reinterpretation; [and] the commodification of a distinct historical narrative.”

Those who travel to Alaska to watch the Iditarod are also deeply involved in the practice of salvage tourism, stimulating the economies of smaller Alaskan villages which are dependent on the attention the race brings. While this may be a more subtle, implicit aspect of some tourists’ trips to Alaska, for others it is this preservation of indigenous culture that motivates their travels. A master’s thesis by Paulien Becker, from the University of Tromsø in Norway, interviewed tourists attending the Iditarod about their motives for visiting. One respondent, who had visited Alaska on multiple occasions, responded “ I love talking to the people and learning about what brought them here and why they stayed. Talking to native Alaskans about their traditions and culture is priceless.’’ This marketing of the Iditarod as a way for non-indigenous tourists to connect with indigenous culture is aligned with the principle of salvage tourism and has certainly contributed to the survival of Alaskan dogsledding, though it has certainly been modified from its original form.

However, preserving the practice of dogsledding faces strong challenges in the modern era. A recent article from Fortune magazine analyzed the decline of the Iditarod race in the last few years. This decline was on full display during the 2023 race, which hosted the fewest competitors ever, fewer than even the first full-length race in 1973. Many mushers believed that the rising costs of training caring for a sled dog team, combined with the relatively meager payout for the winner, made participating economically infeasible for many competitors. During the fall and winter seasons, teams will train and compete in smaller dogsled races in preparation for the start of the Iditarod in March. In the summer, many mushers will supplement their income by taking part in the tourism industry, offering sled dog rides to visitors who come to experience Alaskan life. Unfortunately, the recent combination of high inflation and a decline in tourism due to COVID-19 has caused many mushers to drop out, unable to keep up with the expenses of putting together an Iditarod team.

Another more long-term threat to the practice of dogsledding is climate change, as rising temperatures impact the amount and quality of sleddable area and cause thinner ice. Rick Thoman, a climate specialist from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, writes that even a small amount of melting can threaten the safety of dogsled teams, since “it just has to be at the point where the ice is not stable.” As threats to the long-term sustainability of the Iditarod and of the greater dogsledding practice loom large, there still remains hope that the tradition will survive. One optimist is Brent Sass, a Minnesotan dog musher and longtime Iditarod participant who won the race in 2022. Speaking with Fortune magazine, Sass expressed his belief that the sport will see a comeback as the economy recovers, and the costs of maintaining a dog team settle back down. Also, in a nod to tradition, the 2023 winner was Ryan Redington, grandson of Iditarod co-founder Joe Redington, Sr. and an Inupiat Alaska native. The second and third place finishers were also Alaska natives, a powerful signal that the sport has not strayed too far from its indigenous roots.

Acknowledgements

Massive thanks to Dr. Judith Miller for all her help and support on this project! Also a huge thank you to the University of Alaska Anchorage Consortium Library Archives for providing permission to use their photograph.

Bibliography

Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence. Alaska Population Trends and Patterns, 1960–2018, by James A. Fall. Juneau, 2019.

Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence. The Use of Dog Teams and the Use of Subsistence-Caught Fish for Feeding Sled Dogs in the Yukon River Drainage, by David B. Andersen. Technical Paper No. 210. Juneau, 1992.

Ameen, Carly, Tatiana R. Feuerborn, Sarah K. Brown, Anna Linderholm, Ardern Hulme-Beaman, Ophélie Lebrasseur, Mikkel-Holger S. Sinding, et al. “Specialized Sledge Dogs Accompanied Inuit Dispersal across the North American Arctic.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 286, no. 1916 (2019): 20191929. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.1929

Aporta, Claudio, and Eric Higgs. “Satellite Culture: Global Positioning Systems, Inuit Wayfinding, and the Need for a New Account of Technology.” Current Anthropology 46, no. 5 (2005): 729–53. https://doi.org/10.1086/432651.

Arwezon, Bob. 1973 Iditarod Start in Anchorage. February, 1973. Photograph. Anchorage, February 1973. Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage.

Becker, Paulien. “The Different Types of Tourists and their Motives when Visiting Alaska during the Iditarod.” Master’s thesis, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, 2014.

“Dorothy G. (Guzzi) Page.” City of Wasilla, AK. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://www.cityofwasilla.gov/services/departments/museum/history/dorothy-page.

“Dorothy Page Honored.” Iditarod: The Last Great Race. Iditarod Trail Committee, May 3, 2018. Last modified May 3, 2018. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://iditarod.com/dorothy-page-honored/.

Foss, Katherine A.. “Racing ‘The Strangler’: The Nome Diphtheria Outbreak of 1925.” In Constructing the Outbreak: Epidemics in Media and Collective Memory, 149–72. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2020.

Francis, Karl E. “Decline of the Dogsled in Villages of Arctic Alaska: A Preliminary Discussion.” Yearbook of the Association of Pacific coast Geographers 31, no. 1 (1969): 69-78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24041087.

Hall, Charles Francis. Life with the Esquimaux: The Narrative of Captain Charles Francis Hall of the Whaling Barque George Henry from the 29th May, 1860, to the 13th September, 1862. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

“Iditarod Co-Founder’s Grandson Ryan Redington Wins Dog Race.” The Associated Press, March 14, 2023. Last modified March 14, 2023. Accessed May 2, 2023. https://www.nbc15.com/2023/03/14/iditarod-co-founders-grandson-ryan-redington-wins-dog-race/.

Jones, Preston. Empire’s Edge: American Society in Nome, Alaska, 1898-1934. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2007.

Kaufman, Michael T. “Joe Redington, Co-Founder Of Dog Sled Race, Dies at 82.” The New York Times, June 27, 1999.

Lantis, Margaret. “Changes in the Alaskan Eskimo Relation of Man to Dog and Their Effect on Two Human Diseases.” Arctic Anthropology 17, no. 1 (1980): 1–25. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40315965.

Phillips, Katrina. Staging Indigeneity: Salvage Tourism and the Performance of Native American History. UNC Press Books, 2021.

Simpson, Sherry. “‘DOGS IS DOGS’: Savagery and Civilization in the Gold Rush Era.” In The Big Wild Soul of Terrence Cole: An Eclectic Collection to Honor Alaska’s Public Historian, edited by Frank Soos and Mary Ehrlander, 59–76. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2019. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv21fqhzt.8.

Smith, Valene L. “Eskimo Tourism: Micro-Models and Marginal Men.” In Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism, edited by Valene L. Smith, 2nd ed., 55–82. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fhc8w.7.

“The Beginning.” Iditarod: The Last Great Race. Iditarod Trail Committee, February 4, 2012. Last modified February 4, 2012. Accessed April 26, 2023. https://iditarod.com/about__trashed/the-beginning/.

Thiessen, Mark. “The World’s Iconic Iditarod Dog Sled Race Has the Fewest Competitors Ever Because Its $50,000 Prize Isn’t Enough to Keep up with Inflation.” Fortune. Fortune, March 1, 2023. Last modified March 1, 2023. Accessed April 26, 2023. https://fortune.com/2023/03/01/inflation-hurts-contestants-iditarod-dog-sled-race-alaska/.