Yiqing Hu

Since Tokyo is a metropolitan city that attracts hundreds of thousands of travelers from around the world, many signs on the road multiple languages, such as English, Chinese, and Korean. While you can see different languages, you can also hear multiple languages, not from the tourists, but from the announcers in the street and in the subway. Nevertheless, Japanese is the most prominent language and you can seldom see foreign languages popping on big screen or large façades along the popular streets in Shinjuku and Shibuya. Overall, most foreign languages appear in public spaces where visitors flow rate is relatively high, such as tourist spots and subways. In addition, Tokyo is very friendly to handicapped by providing varied language tools for them, such as braille and whiteboards. Nonetheless, travelers come to experience the exotic Japanese culture so Japanese language remains the sole language of focus in every part of Tokyo in terms of the Japanese characters’ sizes and their central positions.

Foreign languages in the subway and tourist spots are mainly present for practical purpose, not aesthetical. Train announcements are first played in Japanese and then in English. In the case of the train station at Narita International airport, the announcements are played in at least four languages: Japanese, English, Mandarin Chinese, and Korean. Similarly, road signs and directional signs in the subways are also written in Japanese and foreign languages. For example, the sign that denotes exit and transferable line in Akihabara station is written in Japanese with a larger font, English, Chinese, and Korean (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: An exit sign in Akihabara station

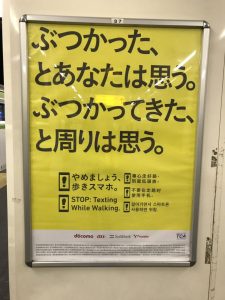

There is also warning signs or posters near these crowded public areas in foreign languages. What is different in this case is that each translation is not a direct translation of the original Japanese text. For instance, this sign in Tabata station asks people to not look at their phone while walking (See Figure 2). The largest text in Japanese, describes a common scenario, means “‘We bumped into each other!’ You may have thought that, but others around you think you bumped into them.” The bottom texts in different languages bring out the real underlined meaning. The two larger texts are in Japanese and English. Traditional Chinese, Simplified Chinese, and Korean follow up. Interestingly, although they convey the same meaning, their exact meanings are a bit different. The text in Japanese means, “Let’s stop it, walking smartphone (smartphone zombie),” white the text in English reads “STOP: Texting While Walking,” putting an emphasis on “texting.” What is more interesting is that the traditional Chinese translation does not match the simple Chinese translation. The traditional Chinese translation reads, “Focus on your road, don’t be someone whose head is always lowered.” On the other hand, the simplified Chinese boringly reads, “Don’t use your phone when you are walking.” (I do not speak Korean so I cannot examine the Korean translated text.) Designer of this poster has incorporated the respective cultural pop language of “smartphone zombies” in each of the translation.

Figure 2: A poster warning people to not use their phone while walking in Tabata station

In another sign in front of a popular ramen restaurant called Mutekiya in Ikebukuro, multiple languages are used to inform people from other cultures that lining up to hold a place for friends is considered as cutting line in Japan (Figure 3). Although it is not clear in the picture, this notice is repeated mentioned on the wall in different language. It is written in traditional Chinese, English, Korean, Thai, and French. Similarly, the no smoking warning is also written in these five languages. Note how Japanese is not used in these notices, signifying that these are local norms that Japanese people follow regularly. Even when Japanese is used in the top notice about not cutting the line, the Japanese text is much smaller than the foreign language warnings.

Figure 3: A warning sign in front of the ramen restaurant Mutekiya in Ikebukuro

Despite the fact that Japanese people have limited space to put as many languages to maximize visitors’ understanding of the situation, they have tried to incorporate a QR code, which you can scan and the system will translate the text into the detected language of the user (See Figure 4). Similarly, the foreign language translations are not literal. While the Japanese language reads “Button for audible walk signal,” the Chinese reads “a prompt tone button specially set for blind people.” The foreign language text usually gives more information that the Japanese text.

Figure 4: A sign explains the purpose of the button in Surugatai Road

In Tokyo, not only “speakable” languages are used to guide people, “non-speakable” languages are also used to help the handicapped. For example, you can see braille in signs as well (See Figure 5 and 6). My advisor had also presented a business card of an NGO personnel

with English, Japanese and braille printed. Although I did not take a picture, stores and ticket windows in the subway offer a whiteboard and markers so you can choose to talk with the staffs in “writings.” These language tools help the blind, deaf-mutes and other handicapped citizens.

Figure 5 (left): Braille on train doors on the Keihintohoku Line

Figure 6 (right): Braille on the exit door in Mark City shopping mall in Shibuya

If we bypass these details of “foreign” languages and look at the big picture, we will most likely only notice Japanese language around us in Tokyo. In the end, travelers come to experience Tokyo as an exotic place filled with Japanese culture and language. Therefore, most façades on popular streets are usually only written in Japanese or the stores’ Romanji characters (See Figure 7). In turns, the Japanese buildings filled with Japanese elements and Japanese characters provides an authentic feel of the culture and thus the language serves both an informational purpose to show what the store is about and a commercial purpose to attract tourists. Foreign languages, on the other hand, are used to help foreign visitors to be able to navigate around the city in transportation centers and on the road.

Figure 8: Ameyoko Shopping Street in Ueno

Very interesting essay. I have always wanted to visit Japan but was worried about the language barrier. From what you’ve written it seems that English speakers would do just fine.

That’s really interesting, the omission of Japanese in signs signifying the direct addressing towards tourists, as well as that the translations between languages for the same sign differ! It seems like they really try to capture the different nuances between different languages and how they are spoken/used colloquially in order to most effectively get their messages across!

That’s so interesting. I loved the part about the translation of the warning sign. Learning a language is something that is new to me and that I have just recently started doing with Russian. The words of my professor in Russian definitely hold true here. When translating, you cannot just go word-from-word, you must go idea to idea. Different cultures have different phrasing and even humor that they may wish to convey in their signs. Language isn’t just words, it is absolutely ideas and your story here illuminates that.

I think your observations about language around Japan is very interesting. I am surprised by the amount of translations there considering Japan’s strict laws on how long foreigners are allowed to stay in Japan and the increasing focus on Japanese identity. However, it also makes sense that Japanese cities focus on these translations considering it is a major tourist destinations and economic hub in East Asia.

It is especially important since Tokyo Olympics is coming soon in 2020 so there has to be translations for the tourists!

Hi Yiqing,

Thank you for a very interesting and comperehensive post on Tokyo. I found it very interesting when you explained how in Japan the signs are the most multi lingual in areas where it is expected to have the most tourism traffic. I found this to be quite the opposite in Dublin, as many of the Tourist signs were written in Gaelic first and then English second, despite the fact that these signs are directed soley to tourists.

Hi,

I found your post about Tokyo very informational and an overall helpful tool. Your inclusion of “non-speakable” languages is a very interesting point, as the handicapped community is often forgotten. I commend Japan for its inclusive efforts and am hopeful that this use of language promotes a more welcoming environment for those marginalized communities.