Sam Miller

Professor Bledsoe

Linguistics 343 Essay 3

6/28/2019

Berlin is a melting a pot of cultures and languages. As a German city, the German language is predictably inescapable. Beyond that, however, one can find many other popular languages that one might expect to see or hear in a city of this size, including English, French, Russian, and so on. Berlin is a political and cultural capital of the world, and its linguistic landscape reflects that idea.

The history of Berlin is crucial in understanding its current linguistic climate. This city was not only literally divided for much of the Cold War but was ideologically divided as well. While the Soviet Union controlled East Berlin, the Americans, the French, and the British each claimed their own sectors in West Berlin. This divide occurred immediately after World War 2 and lasted up until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Therefore, the reunification of Germany is a relatively recent event, and the city is still obviously feeling the effects of over 40 years of enforced division. Many of these effects are clearly visible today, from the architecture to the culture, to the language, and so on. For instance, one is much more likely to see languages like Russian and Georgian, which were countries that comprised the former Soviet Union, in East Berlin than they would in West Berlin. Lastly, because West Berlin was divided into three sectors among the Allies, you can also find a surprising amount of French here. The geographical division of Berlin has clearly played an important role in the development of all the different languages that flourish here today. The most famous example of this is probably the sign that said, “You are now leaving the American sector,” in English, French, German, and Russian.

Aside from German, the most common language in Berlin is certainly English. Everyone here speaks German first and foremost, but if that is not an option, they will likely switch to English. When I approach someone, I typically say “Sprechen Sie English?” to formally ask if they are able to speak English, and very rarely do they answer “Nein.” English is a global language and is certainly more widely taught around the world than German, so most people I meet here can converse with me, even if they only speak a little. Many signs in Berlin reflect this fluidity of language by displaying both English and German. For instance, the sign below puts its service, arguably the most important part of a business sign, in English but its tagline (which translates to “life is not always perfect, but your hands and feet can be”) is in German. This is likely because they know that any German who sees that sign can likely understand both parts, and anyone who does not speak German can still recognize what type of business they are.

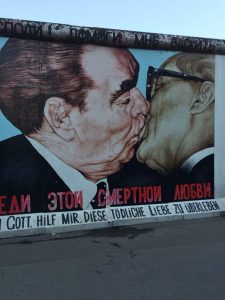

Another critical component in understanding the linguistic landscape of Berlin is the role that graffiti plays in its culture and history. Graffiti conforms to the traditional definition in that it is the “linguistic outward appearance of a place,” but it always conforms to Leeman and Modan’s model in that it can have a lot of subjective and ambiguous qualities (Leeman and Modan, 333). The entire city, especially East Berlin, is covered in graffiti and street art that gives it a very grimy and urban feel. Many of this graffiti is political, some of it is just silly, but all of it contributes to making Berlin a unique city. The language of the graffiti is typically in Russian, German, or English. The best example of this is at the East Side Gallery — the longest section of the Berlin Wall that still stands – where the murals, street art, and graffiti are popular tourist attractions. In the following two examples, the first picture is of a mural (slightly cut off) that translates to “It is necessary to break down many walls,” and is covered in a slew of other politically tinged graffiti in various languages, while the second picture famously says “Help me stay alive among this mortal love!” The use of language in German graffiti, I would argue, is honest in that it is not commodified in the way Leeman and Modan discuss. Rather, these two examples show the integral role that graffiti plays in encapsulating the history of Berlin and developing its contemporary culture, as well as showing how these ideas manifest themselves linguistically.

Works Cited:

Leeman, Jennifer, and Gabriella Modan. “Commodified Language in Chinatown: A Contextualized Approach to Linguistic landscape.” Journal of Sociolinguistics, vol. 13, no. 3, 2009, pp. 332–362.,

“You Are Leaving The American Sector.” World of Signs, worldofsigns.com/signs/586/you-are-leaving-the-american-sector/.

Interesting discussion of Germany’s linguistic landscape. I really like your discussion on the history of the city and how that plays into the landscape. I have learnt a lot about German history during the Cold War so its interesting to see that that still has an effect on the linguistic landscape today!

It was interesting how you talked about the sociopolitical past and history of Germany to put into context the linguistic landscape. It is interesting that there is a mix of past history and a multicultural modern society of Germany.

Hey Sam! Interesting article about Berlin’s linguistic landscape! I really like your insights on historical influences on current language uses in Berlin. Discussion on Berlin’s non-commodified graffiti is also unique. Nice pictures!

Great analysis of the impacts that sociohistorical events have had on Berlin’s linguistic landscape! It is amazing to see the vast number of languages spoken in Germany as a result of these events, and how even the contemporary culture is being impacted, such as in the cases of the graffiti. I also thought it was interesting to compare the way English is used on signs in another European city as compared to how it is used here in Dublin.

I share a similar experience with you when navigating through Hong Kong! Rarely do I ever run into someone who doesn’t know how to speak/understand English. I definitely agree English is a global language; people will most likely know some of it even though never actually learning it.

I really liked reading about the graffiti you mentioned. I feel like I spent all my time thinking about stores and signs when I analyzed Dublin’s linguistic landscape, but street art is such an important expression of beliefs and ideas that it definitely shouldn’t be ignored. It reminded me of certain murals I’ve come across here which are also often political in nature, relating to “The Troubles” in Northern Ireland.

Hi Sam,

I found it quite interesting how the geopoliticial atmosphere surrounding Berlin has gone to create such a multilinguistic society in which you’ve found yourself apart of. I appreciated how you included Berlin’s historical background as part of your blog post, as it helped to fully encompass how it has shaped the current linguistic landscape. Lastly, I found it intruiging that you included commentary of the graffitti in Berlin, as graffiti is not something I would have thought to include in a discussion on linguistic landscape.