New York City is often referred to as the hub of financial services and culture. Looking at the popularity of areas like Chinatown, Koreatown, and Little Italy, it is no surprise why New York City is highly regarded to be culturally diverse. However, after experiencing these areas first hand, it was most noticeable that the majority of the language used on the signs was identical to the language spoken throughout the area. A completely reasonable explanation for many restaurants and shopping malls in regard to their usages of these languages. It was through my exploration and research on East Village that revealed the gentrification occurring within East Village, but also revealed the outside forces that come into play in a restaurant’s adoption and usage of a foreign language.

To further develop my understanding of restaurants’ signage and menus in East Village, I compared the racial demographics of Koreatown and Chinatown to East Village. The expected discovery was that in Chinatown, the majority of the population was Asian at 76.1% (StatisticalAtlas). In Koreatown, Asians were a close secondary majority at 45.5% (ThePeoplingofNewYork). Corporations and restaurants intentional usage of multilingual signage had a purpose and they weren’t entirely for them to become a “floating signifier that [would] be used to signify, or to sell, not just things Chinese but anything at all” (Leeman and Modan, 353-354). These multilingual signages were displayed to also benefit the majority population in that area and as a result, it became increasingly difficult to identify whether gentrification was the main reasoning behind these signs.

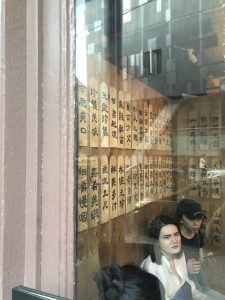

East Village, on the other hand, told a very different story. Similar signages were used but more importantly, decorative aspects were displayed in languages fitting the cuisine of the restaurant (Figure 1). The question was whether the intentional inclusion of visual designs like Figure 1 were to accommodate the living population in the area or were they purely symbolic? Initial observations that the neighborhood mostly spoke English and not Chinese immediately leaned me towards the idea found in Leeman and Modan’s (2009) article that the “main thrust of Chinese is symbolic” (Leeman and Modan, 352). Further research revealed that Asians only accounted for 13.9% of the racial breakdown for East Village, New York, New York, while the majority was White by a longshot (StatisticalAtlas). Similar to what Leeman and Moden observed was happening in Washington DC, Chinese restaurants in East Village were employing Chinese without the need for those Chinese characters to be used in a speech situation, clearly displaying their intentions to market themselves as authentic.

Chinese Decorations within a restaurant. The tablets are food phrases in Chinese and aren’t actual dishes.

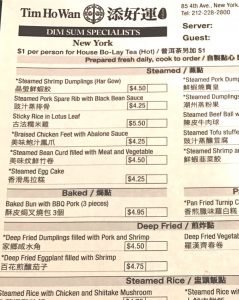

In support of the previous paragraph, the same targeted demographic can be revealed through the menu of a Chinese dumpling house (Figure 2). Though the menu includes both English and Chinese, it can be seen that the primary language of the menu is English with Chinese characters below each English description of the plate. However, it is critical we realize that the Chinese provided in this menu can be used “in order to participate in a service encounter” (Leeman and Modan, 352). An observation that is essential in differentiating Leeman and Modan’s discoveries in Washington DC from East Village and brings to light that a restaurant’s inclusion of cultural aspects and foreign languages may not be entirely because of a profitable desire for themselves to appear more sophisticated and cultural.

Menu of Tim Ho Wan

Though the inclusion of decorations displayed in Figure 1 are purely symbolic and are utilized as cultural capital to market a sense of authenticity, Figure 2 also imperatively sheds light on how a lot of restaurants have intentions that may not be as one sided as they seem. The implementation of culture in restaurants can often be seen as an intention to make their restaurants become more appealing due to authenticity, but as seen through Figure 2, it may also serve an entirely different purpose. A purpose that can be potentially linked to respecting their homage, increasing accessibility to foreign customers, and improving convenience for their potential service men and women who may only speak a foreign language. Regardless of a restaurant’s intention, the exploration of East Village has only further revealed the complexity of New York City’s linguistic landscape and immense cultural diversity.

Works Cited

“Race and Ethnicity in Chinatown, New York, New York (Neighborhood).” The Demographic Statistical Atlas of the United States – Statistical Atlas, statisticalatlas.com/neighborhood/New-York/New-York/Chinatown/Race-and-Ethnicity.

“Race and Ethnicity in East Village, New York, New York (Neighborhood).” The Demographic Statistical Atlas of the United States – Statistical Atlas, statisticalatlas.com/neighborhood/New-York/New-York/East-Village/Race-and-Ethnicity.

“The Peopling of New York » Demographics and Statistics.” The Peopling of New York RSS, eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/berger2010/a-taste-of-the-world/the-history-of-koreatown/demographics-and-statistics/.

Leeman, Jennifer, and Gabriella Modan. “Commodified Language in Chinatown: A Contextualized Approach to Linguistic Landscape.” Journal of Sociolinguistics, vol. 13, no. 3, May 2009, pp. 332–362., doi:10.1111/j.1467-9841.2009.00409.x

i found it interesting how you talked about the restaurants around New York City and the use of languages as an advertisement appeal. Since New York is such a diverse and growing city it is easy to just assume it has a linguistic landscape that is used to help those of different nationalities to get around. I have never thought much about how using certain languages can appeal to a certain “authentic” advertisement.

Your comments about the linguistic landscape of NYC are very interesting. I, like you, wondered about the different languages used in the East Village, and can definitely agree that this city’s linguistic diversity is immense. Whether or not authenticity is the aim of these restaurants is a good question, but I did find that many of the establishments in Little Tokyo (in East Village) seemed to be a bit more intent on catering to customers who spoke Japanese, which I found interesting.

I really enjoyed reading your analysis of NYC’s linguistic landscape, specifically in the East Village. I spent some time in the city earlier this summer, and I stayed in the heart of Chinatown. I was struck by how the restaurants and shops directly around me in Chinatown had signage primarily in Chinese, with little English translations. However, if I walked only a few blocks away and into the Lower East Side, gentrification and using languages other than English to market “authenticity” was easily noticeable. I appreciated your discussion of this phenomenon and I’ll be curious to see how the diverse linguistic language of NYC will change in the future.

Hi,

I love your emphasis on the commodification of the Chinese language, especially in restaurants as shown by Figure 1. It is very interesting that areas will try and cater to specific communities to seem more “authentic”, but don’t really understand the meaning behind their signage. The linguistic landscape seems diverse but I wonder if similar demographics tend to follow each other when migrating – whether there are efforts for inclusion or just assimilation?

I think you did a great job applying what we have learned from the essay to the real analysis of those streets. I think your analysis overall is very comprehensive and I could not agree more to your analysis about symbolic signs at East Village.

I really learned a lot by reading your findings and analysis. I particularly like the picture of Chinese dishes as decoration. In this case, a language is no longer a communication tool, but more like a sign, a picture, an advertisement. Even more, the concept of culture doesn’t hold its original meanings in the second-hand areas such as Chinatown or K-town in another country.