James Steffen, Film and Media Studies Librarian (University Libraries), recently received an excellent review in the Times Literary Supplement for his book, The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov. The review, written by Julian Graffy, a professor of Russian Literature and Cinema in the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, described Steffen as a “sure-footed elucidator of the mysteries of the director’s oeuvre.”

You can read the review below:

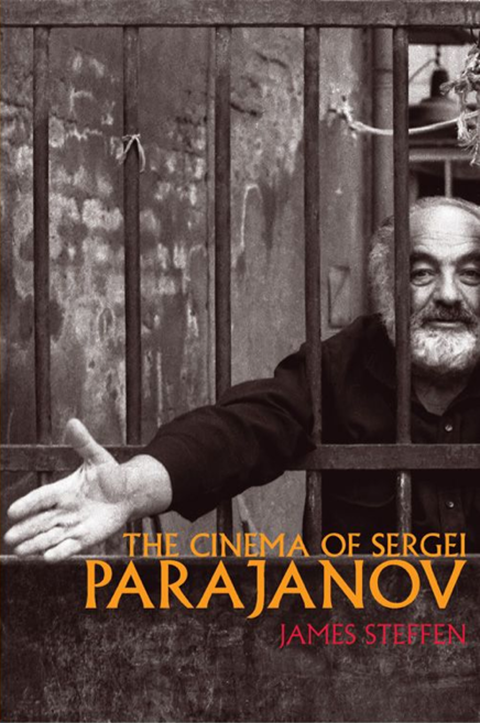

THE CINEMA OF SERGEI PARAJANOV

326pp. University of Wisconsin Press. Paperback, $29.95 (£24.95). 978 0 299 29654 4

The two most admired films of the Tbilisi born Armenian director Sergei Parajanov (1924-90) combine loving evocations of a distant world with extension of the possibilities of cinematic form. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964), taken from Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky’s novella of 1911, is a story of tragic love set among the Carpathian Hutsuls. It combines attention to the rituals and material culture of the Hutsuls with a vibrant colour palette, dynamic camerawork and an inventive soundtrack. The Colour of Pomegranates (1969) is a stylized, poetic evocation of the life of the eighteenth-century Armenian poet and bard Sayat-Nova, as well as a broader examination of the role of the artist. The first complete film made in Parajanov’s late tableau aesthetic, with beautiful compositions representing key stages of the poet’s life, almost no dialogue and an ambitious “audio-collage” (in James Steffen’s phrase) composed by Tigran Mansurian, The Colour of Pomegranates led Jean-Luc Godard to say that it had given him new faith in himself and his own cinematic technique.

Steffen is a sure-footed elucidator of the mysteries of the director’s oeuvre. His is the first English-language book on the subject, and combines perceptive readings of the films with erudite interpretations of Transcaucasian history and culture and of Soviet cinema and politics, all in the context of the vicissitudes of Parajanov’s life. And what an eventful life it was, marked by three periods of imprisonment, the murder of his first wife a month after their marriage, allegedly by her relatives, and increasingly open confrontation with Soviet authorities.

After studying in Moscow, Parajanov was sent to work at the Kiev Studios, where he made four features between 1954 and 1962. Steffen finds little to praise in them but it is fascinating, in retrospect, to see how much eccentricity, and how many purely decorative sequences, can already be found in his two films about young workers, The First Fellow (1958) and The Flower on the Stone (1960-62). Parajanov’s subsequent career is littered with unmade and aborted films, and Steffen’s discussion of these is deeply suggestive, particularly when he writes about Kiev Frescoes (1966), set in contemporary Kiev but with memories of the war still vivid. All that remains of the film is thirteen minutes of screen tests; nevertheless, the stylized movements of its actors provide a missing link between Shadows and The Colour of Pomegranates.

As the years went by, Parajanov became ever more outspoken in his criticism of those he saw as curtailing his freedom of expression. Though his arrest in 1974 was ostensibly on charges of homosexuality, it is clear that his association with nationalist Ukrainian intellectuals had placed him in the firing line. After his release from the camps he made two more Oriental tales, but his long planned autobiographical project, A Confession, had to be shut down after three days of shooting due to Parajanov’s ill health. He died of lung cancer in 1990. James Steffen has given us an absorbing portrait of the artist as brilliant gadfly, agent provocateur and courageous defender of his own personal vision.

– Julian Graffy

Leave a Reply