Earlier this year, Arya Basu, a visual information specialist working in the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS), conducted a virtual reality (VR) experiment in the Woodruff Library that led to some fascinating hypotheses about the future of education.

Arya believes his results suggest that VR should be the classroom of the future.

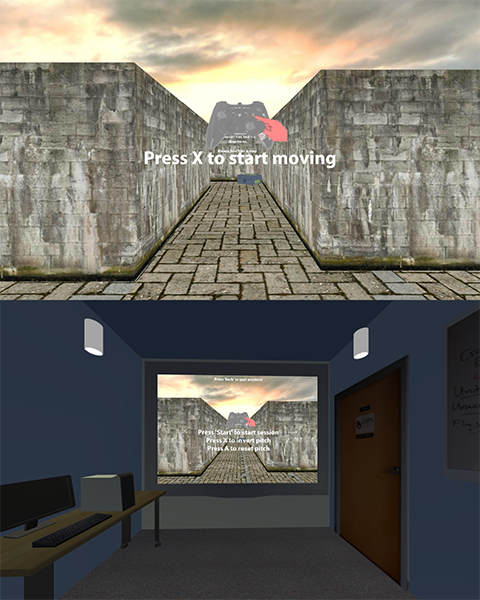

In the experiment, users had to navigate a pair of virtual mazes, one wearing VR goggles and using a wireless gaming controller to control movement and the other using VR goggles in which a person had to actually move their head to see around the maze. Each user was also asked a series of questions about their prior experience as a “gamer,” someone who likes to play video games.

What Arya found was that gamers navigated the first maze faster than non-gamers. However, in the second maze where the users were “untethered,” meaning they used full control of their heads within the maze, both sets of users spent longer in the maze, equally taking their natural time to explore their options.

What’s the breakthrough that this suggests? That a standardized classroom environment in VR can be created for all types of learners.

According to Arya, “Pure head control introduces the normalization of spatial behavior. As such, immersive VR causes a normalizing effect that filters out existing bias between gamers and non-gamers.” Gamers typically figure out shortcuts to complete tasks the quickest way possible. In a classroom, students who act like gamers and find quicker ways to compile knowledge, such as cramming the night before a test, may score well on tests without actually achieving a transfer of sustainable knowledge.

In a VR classroom, everyone would be forced to slow down and truly absorb the material. This approach would remove time as a metric for learning. Arya believes that VR is more aligned with reality than current classroom approaches.

“These are compelling results,” says Arya. “They take us one step closer to saying we can substitute VR design over game-like design when it comes to pedagogy.” Arya thinks we should turn our focus away from game design in classrooms and move more toward creating real experiences. In theory, the results would be slower, but the learning would increase.

The point here is that in immersive VR, you can filter out biases. You can make classroom experiences that are fairer at the expense of speed but to the betterment of learning.

“We now have a statistical basis for proving this,” said Arya. He worked closely with colleague Michael Page to develop the spatial analysis used to calculate the stats in this experiment.

One downside of the research is “cybersickness.” A percentage of users that are untethered in the maze develop nausea and a touch of vertigo (including the author of this article). “It’s something researchers in the industry are looking at.”

Where do we go from here?

The next step will be a test of learning. Arya plans to define the metric of being a gamer, and start injecting immersive interfaces into actual classes. In this way, researchers will be able to investigate the physical viability of VR learning and create an evaluation metric.

Concluded Arya, “When we know how you learn, we can create more personalized assistance methods. Basically, this is a stepping stone towards the real use of artificial intelligence in education.”

Leave a Reply