By Amy Lazzaroni

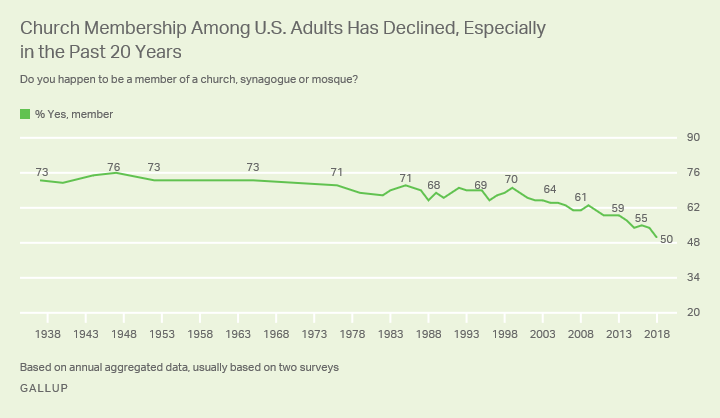

For some time now, there have been discussions about the alleged decline of church

attendance in the United States. According to a 2021 Pew Research Center survey, three-in-ten

American adults considered themselves to have no religious affiliation, almost double the

number from 2007. Only 41% say that religion is “very important” in their lives, down 4% from

just a year before and down 15% from 2007.

Overlapping several of these groups are the people who consider themselves “spiritual but not religious.” There are also a significant number of Christians who consider themselves “deconstructing,” though the term can mean different things for different people. Some deconstruct to a different form of the Christian faith, while others leave faith altogether.

While this downward trend of religious involvement began several years ago, it has become even more complicated due to COVID-19.

Despite the determination of some Christian leaders to hold on to traditional ways of doing church, most churches were already beginning to rethink what worship and community might look like in our time. The near-constant pivoting required by a global pandemic forced leaders to make changes they might never have otherwise considered, and to do so without much time for the endless debate amongst committees for which churches are often known.

And now, on what is hopefully the final decline of COVID-19, pastors are left holding a strange mix of practices – some old, some new – and wondering what should stay and what should go as we enter this next stage. A very recent Pew Research Center study found that, despite more churches operating without pandemic restrictions, more people were not returning to in-person church services. Is it simply that churches aren’t offering what people want, or is there something deeper going on?

I don’t approach this subject with any easy or definitive answers. But based on my

research and experience, I believe our evaluation of this trend is much more complicated than

many discussions suggest. Though I am admittedly drawing significantly on my own personal

experience, I have found that I rarely fit into the generalizations these surveys seem to draw.

While I haven’t attended an in-person church in months, it’s not because I consider myself a

“none” or view my faith as unimportant.

Yes, like many people, I have enjoyed not having to make the effort of getting up, getting dressed, and driving to church. But it’s more than that. Even though my current membership is at a progressive and inclusive congregation (unlike the fundamentalist Southern Baptist theology I grew up with), I still struggle to feel safe at church because of the many ways I have been wounded there before. It’s not about the service times or worship styles, it’s about church altogether.

Especially now, in the middle of all we are experiencing in our world – the devastation in

the Ukraine, rapidly rising inflation, the frightening rise of Christian nationalism, and a political

divide like never before – I feel too raw on a daily basis to voluntarily subject myself triggers at

church that I may never be able to overcome. While I know in my head that faith is best lived

out in community, most of the time it is all I can do to maintain my own personal faith in a way

that feels safe. The vulnerability required by a community seems like too much.

I want to have faith and I want to be part of a community, but there is so much risk in being part of a faith

community – particularly right now – for those of us who have experienced past harm in those groups.

Let me be clear that I am not talking about simply being offended by a person at church or having a difference of opinion from church leadership. In addition to those who have experienced physical abuse at the hands of church leaders, religious trauma is real, and spiritual abuse happens more than we would ever like to consider. For some, the harm they have experienced even presents with PTSD-like symptoms when they try to attend church.

I was surprised to find that Zen Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh connects the two

issues of disconnection from faith and addressing harm in his book Living Buddha, Living Christ.

Thay says, “There are already enough people uprooted from their tradition today, and they

suffer greatly, wandering around like hungry ghosts, looking for something to fill their spiritual

needs. We must help them return to their tradition. Each tradition must establish dialogue with

its own people first, especially with those young people who are lost and alienated” (197).

He also says, “Church authorities must strive to understand the suffering of their own people. The lack of understanding brings about the lack of tolerance and true love, which results in alienation of

people from the church” (197-198).

Before the church tries to evangelize or recruit new members, the church must first repair relationships with its own family, those whose roots are found in Christianity. Churches must begin by owning and addressing the suffering they have caused inside their own walls. The church must begin to “understand the suffering of their own people” and then begin to make genuine, meaningful repair for the damage that has been done. Instead of urging the use of spiritual bypassing, which ultimately causes further harm, churches must be willing to dig deep and look at their part in the damage. It is too easy for churches to place a burden on the victims by telling them to forgive instead of holding perpetrators accountable, or to accuse them of lacking faith when instead harmful practices or policies should be scrutinized.

Among other things, the church must meaningfully address abuse by leaders as well as Christianity’s ongoing history of sexism, racism, xenophobia, and homophobia.

The church must own the harm it has perpetrated in the name of God and Scripture, falsely claiming divine authority to damage, demean, and discriminate. In these most difficult times, people will be unwilling to rejoin church communities if those communities are unsafe. The only way to create safety is through the willingness to genuinely listen, learn, and do better. Only when the church is itself a place of healing and reconciliation can it truly equip Christians to live out their vocation of bringing healing and reconciliation to the rest of the world.