References:

Ghosh, S. K., Priya, A., & Narayan, R. K. (2021). Raymond de Vieussens (1641–1715): Connoisseur of cardiologic anatomy and pathological forms thereof. Anatomy & Cell Biology, 54(4), 417–423. https://doi.org/10.5115/acb.21.108

Exploring neuroscience while exploring Paris

I see dead people…in crypts. On Wednesday, we went to visit the Pantheon in Paris! “Pantheon” is derived from Greek, meaning ‘temple for all gods.’ However, the French Pantheon was intended not to be a religious symbol or house any religious artifacts. Instead, this Pantheon would be the resting place for those who extended the greatness of France, and assisted France in pursuing its’ national motto: liberté, égalité, fraternité (liberty, equality, and brotherhood.)

While listening to the audio tour, I learned that only men (and, more recently, women) who made their achievements after July 14, 1789, are allowed to be buried at the Pantheon. This is because only those who brought glory to France during ‘freedom’ may be buried there, and July 14, 1789, was the Storming of the Bastille that was recognized as the official beginning of the French Revolution, and every period after that was determined to be free France. This can be seen in the inscription on the first-floor reading “vivre libre ou mourir,” or “live free or die.” Some notable characters featured in the Pantheon are Joan of Arc, immortalized in a mural along the side chambers, Victor Hugo in his vault, and some enlightenment writers and philosophers such as Rosseau and Voltaire. I found it particularly intriguing how Joan of Arc, a distinctly French religious feature, could be so beautifully combined with secularism to intertwine both Christianity and secular versions of French history. Our final stop on our visit was to the tomb of Marie Curie. Marie Curie famously received radiation poisoning during her lab work, which eventually lead to her death via aplastic pernicious anaemia. During her time working with radium, she began a fleet of mobile X-ray devices to allow doctors’ to locate shrapnel wounds in soldiers’ during WWI. She then founded the Instiut du Radium, which is now an oncology research center. It made me wonder how far oncology radiation therapy has come since the time of Marie Curie. I found an article that gave an overview of the historical development of radiation therapy. Following the increase in empiricist medicinal practices, radiation therapy has grown to be more focused on local tumor destruction and reduction of side-effects. For instance, in clinical trials it was found that radiation therapy improves local control of a tumor and increases survival rates of breast cancer following first breast-conserving surgery, and then mastectomy if absolutely needed (Thompson et. al, 2018). It’s interesting to see this development in the thinking behind physiology and medicinal practices over 150 years after Curie.

References:

Thompson, M. K., Poortmans, P., Chalmers, A. J., Faivre-Finn, C., Hall, E., Huddart, R. A., Lievens, Y., Sebag-Montefiore, D., & Coles, C. E. (2018). Practice-changing radiation therapy trials for the treatment of cancer: Where are we 150 years after the birth of Marie Curie? British Journal of Cancer, 119(4), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0201-z

Compasses, calculators, and robots, oh my! Today, we attended the Musée des Arts et Métiers to learn all about scientific instruments throughout the ages. One of my favorite things in the museum was a device from the late 18th century used to ferment wine. Wine fermentation is truly an art form and has taken centuries to perfect into modern wine we drink from a bottle today and getting to see an original fermentation device was such an intriguing experience.

We also got to view a magnetic drum device, a precursor to the modern calculator we use today. It strangely resembled a typewriter. We also viewed different communication devices from years (and even centuries) past, including the first press-cylinder printer and an original Nokia from the early 2000s. Additionally, we saw a Russian extra-terrestrial rover that could communicate from outer space! Lastly, my favorite thing we got to see was a thermoscope from 1592 that once belonged to Galileo! In fact, with some further research after leaving the museum, I discovered that Galileo actually introduced the first thermoscope thermometry which would eventually evolve to the modern thermal imagery we see today!

Evidently, this invention sprung medicinal science forward towards modern Western biomedicine. Fever has always been one of the most common medical indicators of ailment, and it made me ponder how temperature correlates with neuroscience and potential brain injuries. I found a recent study that discussed the relationship between body and brain temperature in rodents with traumatic brain injuries (TBIs). Previous research had previously indicated that extreme temperature deficits or increases may affect the implications of brain injuries. Researchers decided to compared rats that had acquired traumatic brain injuries to uninjured rats both under general anesthesia and not under general anesthesia. When under anesthesia, there was no significant temperature difference between rats with TBIs and rats without TBIs. However, rats who were under anesthesia had significantly lower temperatures than rats not under anesthesia, suggesting that anesthesia alone caused a decrease in temperature. When rats had not been put under anesthesia temporalis muscle temperature correlated well with brain temperature, but rats with TBIs and rats without TBIs did not differ in temperature. This allowed the researchers to conclude that temporalis muscle temperature is a good indicator of brain temperature, however, brain temperature itself is not necessarily indicative of a TBI. After reading this article, it was very intriguing to consider how far the science of temperature in medicine has come since the days of Galileo.

References:

Jiang, J. Y., Lyeth, B. G., Clifton, G. L., Jenkins, L. W., Hamm, R. J., & Hayes, R. L. (1991). Relationship between body and brain temperature in traumatically brain-injured rodents. Journal of Neurosurgery, 74(3), 492–496. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1991.74.3.0492

Ring, E. F. J. (2007). The historical development of temperature measurement in medicine. Infrared Physics & Technology, 49(3), 297–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2006.06.029

This past Friday, we all made the transition from obnoxious American sports fanatics to obnoxious European sports fanatics! Adorning French face paint, we headed up to the top of the stadium to rugby, I mean, football, which was surprisingly brutal physically for the players. I counted 6 potential head injuries for my chosen player, #7. Luckily, it seems that there actually has been extensive research into both the implications of soccer-related head injuries and how they can be prevented as early as youth soccer leagues. In fact, one study looked at implicating behavioral skills training, or BST, into youth soccer programs to demonstrate and enforce a safer means of “heading” the ball that leads to less physical duress. These researchers found that there was vast improvement amongst the players after BST as opposed to players without BST, so perhaps this practice should be implemented in more youth sports programs.

References:

Quintero, L. M., Moore, J. W., Yeager, M. G., Rowsey, K., Olmi, D. J., Britton‐Slater, J., Harper, M. L., & Zezenski, L. E. (2019). Reducing risk of head injury in youth soccer: An extension of behavioral skills training for heading. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.557

Like a French reenactment of Willy Wonka and the chocolate factory (minus the Oompa Loompas), we visited ChocoStory this week to learn a little more about the ins and outs of chocolate making and decorating! From marshmallows to orange peels to chocolate solids, we experimented with several forms of chocolate goodies, even making our own candy bars! Some chose to decorate their delectable treats with corn flakes or Rice Krispie’s, others opted for hazelnuts or coconut flakes.

A picture of me and Joon while decorating our chocolate marshmallows.

Kennedy and I decorating our chocolate bars.

For the majority of our decorating experience, we were given a choice between either milk or dark chocolate. Personally, I prefer milk chocolate, but several of my fellow chocolate decorators around me opted for dark chocolate, which made me wonder why some people may prefer dark chocolate over milk chocolate, or vice versa. This led me to an article on PubMed that investigated the tolerance for bitterness in chocolate ice cream suing solid chocolate preferences. To compensate for the natural bitterness of cacao, many candy/dessert companies will add high levels of milk, sugar, or corn syrup to increase the palatability of the product. Given the current obesity epidemic occurring in the United States and beyond, many experts are concerned about the amount of fattening additives in chocolate desserts. Thus, researchers sought to manipulate the amount of bitterness in chocolate desserts and subsequently observe consumer preferences. The goal of this study was to uncover the threshold for bitterness in chocolate products among a sample of frequent chocolate consumers. The sample was divided into groups that tasted varying levels of bitterness in chocolate, with a control group tasting baseline, “normal” chocolate and each subsequent group tasting increasing bitterness. Added bitterness was simulated using sucrose octaacetate (SOA), a safe food additive that is still strongly bitter at micro molar concentrations. Samples of varying bitterness were manufactured into ice cream at the Berkey Creamery at Pennsylvania State University (PSU). Subjects were recruited from the PSU community via email and indicated their chocolate preferences (milk vs dark) beforehand. As predicted, the group of subjects who indicated that they preferred milk chocolate had a lower bitterness threshold. On the other hand, the participants who had previously indicated that they preferred dark chocolate had a higher tolerance for the bitter SOA additive. Based on this study, I can conclude that I likely would also have a lower bitterness tolerance compared to say Joon who used more dark chocolate than me while decorating.

Overall, I learned a lot of new techniques about chocolate making and decorating through this experience, including how chocolate makers will add other ingredients in order to decrease the bitterness in milk chocolate, and that a lower bitterness tolerance correlates with a preference for milk over dark chocolate.

References:

Harwood, M. L., Loquasto, J. R., Roberts, R. F., Ziegler, G. R., & Hayes, J. E. (2013). Explaining tolerance for bitterness in chocolate ice cream using solid chocolate preferences. Journal of Dairy Science, 96(8), 4938–4944. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2013-6715

Photo 1: a photo of a canine with osteopetrosis, or ‘bone-on-bone.’ Likely caused by a lung infection, the exact mechanism and underlying causes to this unstoppable bone growth are still unknown, however, osteopetrosis can occur in humans as well as dogs. Osteopetrosis is a bone disease in which bones become unusually and alarmingly dense and easily fractured. This condition can be caused by many factors, and is, unfortunately, heritable. This was one of many disease our tour guide mentioned that used to be treated in animals in the exact same manner as it would be treated medically in a human. As previously stated, the current underlying mechanisms to osteopetrosis in canines are currently unknown, but osteopetrosis in humans can be prevented. It’s invaluable that we diverge in our treatment of neurological and other disease between humans and non-human animals, as the mechanisms, anatomy, and responses are inherently different in nature.

A parade through both the intriguing and the bizarre, the curious and stomach-churning, our visit to the Musée Fragonard de l’Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire d’Alfort was truly a mind-bending experience. Our guide, a veterinary student himself, lead us through the so-called “cabinets of curiosities,” a rather popular display to possess among Parisian elite in the past. These cabinets including both non-human animal and human anatomies. Some, such as stomachs, digestive tracts, and other organs, were simply replicas or molds that had been plastered and painted to show anatomical distinctions. In addition, there were several skeletal figures ranging from smaller animals, like cats, to larger animals, like giraffes and camels. One particular skeleton that stood out to me was that of a dog with “bone-on-bone” caused by a lung infection. The specific mechanistic cause was unknown but seeing how thick the dogs’ legs had become with the layers upon layers of bone was incredibly intriguing. One new thing we learned how vastly veterinary science has changed in expanded in a mere century alone. Our guide mentioned how in the past doctors would merely apply human medical science to animals, but since animals have such differing systems from humans, the veterinary school was founded, initially in the center of Paris, then later moved to the city outskirts, in order to further explore how to treat animals specifically.

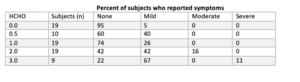

In addition, some displays contained formaldehyde jars with actual body parts, including tissue, genitals, stomachs, craniums, and more kept intact via various preservation methods. At this point, I noticed that myself in particular, as well as a few of my fellow students had to step outside for air or sit down because we started feeling rather queasy. After returning home and still not feeling well, one of my roommates mentioned how the odor of formaldehyde can make some people feel ill, even long after leaving the presence of the chemical. This led me to an article describing the psychophysical relationship between formaldehyde odor and irritation response in healthy non-smokers (Kulle, 2008). The study conducted utilized a 19 subject sample that were exposed to various concentration of formaldehyde (HCHO) over a 3-day period and asked each subject to report their subjective symptoms. The researchers found that the threshold of HCHO of just 0.5 ppm of exposure could cause an odor sensation that may make some feel sick and increasing exposure could cause eye irritation or even nose/throat irritation.

Knowing this, it’s curious to consider how the formaldehyde potentially affected only some of us in the museum, while others remained completely unfazed and continued to the end of the exhibition without any problem.

References:

Kulle, T. J. (1993). Acute odor and irritation response in healthy nonsmokers with formaldehyde exposure. Inhalation Toxicology, 5(3), 323–332. https://doi.org/10.3109/08958379308998389