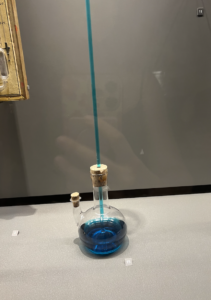

Compasses, calculators, and robots, oh my! Today, we attended the Musée des Arts et Métiers to learn all about scientific instruments throughout the ages. One of my favorite things in the museum was a device from the late 18th century used to ferment wine. Wine fermentation is truly an art form and has taken centuries to perfect into modern wine we drink from a bottle today and getting to see an original fermentation device was such an intriguing experience.

We also got to view a magnetic drum device, a precursor to the modern calculator we use today. It strangely resembled a typewriter. We also viewed different communication devices from years (and even centuries) past, including the first press-cylinder printer and an original Nokia from the early 2000s. Additionally, we saw a Russian extra-terrestrial rover that could communicate from outer space! Lastly, my favorite thing we got to see was a thermoscope from 1592 that once belonged to Galileo! In fact, with some further research after leaving the museum, I discovered that Galileo actually introduced the first thermoscope thermometry which would eventually evolve to the modern thermal imagery we see today!

Evidently, this invention sprung medicinal science forward towards modern Western biomedicine. Fever has always been one of the most common medical indicators of ailment, and it made me ponder how temperature correlates with neuroscience and potential brain injuries. I found a recent study that discussed the relationship between body and brain temperature in rodents with traumatic brain injuries (TBIs). Previous research had previously indicated that extreme temperature deficits or increases may affect the implications of brain injuries. Researchers decided to compared rats that had acquired traumatic brain injuries to uninjured rats both under general anesthesia and not under general anesthesia. When under anesthesia, there was no significant temperature difference between rats with TBIs and rats without TBIs. However, rats who were under anesthesia had significantly lower temperatures than rats not under anesthesia, suggesting that anesthesia alone caused a decrease in temperature. When rats had not been put under anesthesia temporalis muscle temperature correlated well with brain temperature, but rats with TBIs and rats without TBIs did not differ in temperature. This allowed the researchers to conclude that temporalis muscle temperature is a good indicator of brain temperature, however, brain temperature itself is not necessarily indicative of a TBI. After reading this article, it was very intriguing to consider how far the science of temperature in medicine has come since the days of Galileo.

References:

Jiang, J. Y., Lyeth, B. G., Clifton, G. L., Jenkins, L. W., Hamm, R. J., & Hayes, R. L. (1991). Relationship between body and brain temperature in traumatically brain-injured rodents. Journal of Neurosurgery, 74(3), 492–496. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1991.74.3.0492

Ring, E. F. J. (2007). The historical development of temperature measurement in medicine. Infrared Physics & Technology, 49(3), 297–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2006.06.029