Every October, when the Nobel Prize in Literature is announced, readers unfamiliar with the laureate’s work often wonder whether they would enjoy the author’s writings, and which book to start with. This blog introduces readers to this year’s laureate, Hungarian novelist and screenwriter László Krasznahorkai, whose books and films are well represented in the Woodruff Library’s collection.

To begin, Krasznahorkai once described his writing process to The Guardian with characteristic humor and devotion to craft:

Letters; then from letters, words; then from these words, some short sentences; then more sentences that are longer, and in the main very long sentences, for the duration of 35 years. Beauty in language. Fun in hell.

His work has drawn comparisons to Russian author Nikolai Gogol by both Susan Sontag and W.G. Sebald. In 2015, Marina Warner, chair of the Man Booker International Prize committee, praised Krasznahorkai as:

A visionary writer of extraordinary intensity and vocal range who captures the texture of present-day existence in scenes that are terrifying, strange, appallingly comic, and often shatteringly beautiful.

In October 2025, the Nobel Prize in Literature committee honored Krasznahorkai “for his compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art.”

Members of the Swedish Academy recommends starting with any of the following four works:

- Sátántangó (his debut novel)

- The Melancholy of Resistance, described as “a wonderfully dark and darkly funny novel, and like all Krasznahorkai’s works, completely timeless”

- Seiobo There Below, which reveals “a new, finely tuned sense of darkness”

- Herscht 07769: Florian Herscht’s Bach Novel, in which a character from eastern Germany—where Bach once composed—writes a message to Chancellor Merkel as strange events unfold

However, Ádám Holczer, goalkeeper for Hungarian soccer team Soroksár SC and a literary enthusiast, recommends War and War as a good entry point into Krasznahorkai’s oeuvre.

Krasznahorkai’s speech, much like his prose, is reflective and enigmatic. When asked in 2015 which of his books a new reader should begin with, he told The Guardian:

If there are readers who haven’t read my books, I couldn’t recommend anything to read to them; instead, I’d advise them to go out, sit down somewhere, perhaps by the side of a brook, with nothing to do, nothing to think about, just remaining in silence like stones. They will eventually meet someone who has already read my books.

About the author

Born in Gyula, a town near Hungary’s southeastern border with Romania, Krasznahorkai studied law and literature, writing his thesis on Hungarian author Sándor Márai’s experience in exile (Márai’s works are also available in the library). Inspired by Rilke and deeply influenced by Kafka, Krasznahorkai published his first short story in 1977 and his first novel, Sátántangó, in 1985. In 1994, Hungarian director Béla Tarr adapted the novel into a film, despite Krasznahorkai’s initial reluctance to collaborate. Their partnership continued, resulting in several films that are available through Emory Libraries.

Krasznahorkai has published 12 novels (with a 13th forthcoming in November), two short story collections, and numerous essays and lectures. His works have been translated into over 30 languages. He is a member of the Hungarian Digital Literary Academy and the Széchenyi Academy of Literature and the Arts, and has received numerous awards, including the Man Booker International Prize (2015) and the Greek magazine Literature’s Foreign Phrase of the Year award (2018).

While some of his novels (especially his first and most recent) are inspired by life in Hungary before and after 1989, Krasznahorkai’s writing often explores universal human experiences through absurdist lenses. His depictions of the impoverished Hungarian countryside are vivid and poignant. Since 1990, he has traveled extensively, with visits to China and Japan deeply influencing his work. He currently resides in both Vienna and Trieste.

Additional books available at the library

- A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East (2003; English edition 2022)

- Destruction and Sorrow Beneath the Heavens: Reportage (2004; English edition 2016)

- Someone Is Knocking on My Door (essay published in The New York Times, 2013)

- Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming (2016)

- The Manhattan Project: A Literary Diary Presented as Twelve Chance Encounters or Coincidences (2018)

- Spadework for a Palace: Entering the Madness of Others (2018)

Short story collections

- The Last Wolf, Herman: The Game Warden, and The Death of a Craft (2016)

- Animalinside (2010), inspired by paintings by Max Neumann

- The World Goes On (2013/2017)

About his movies

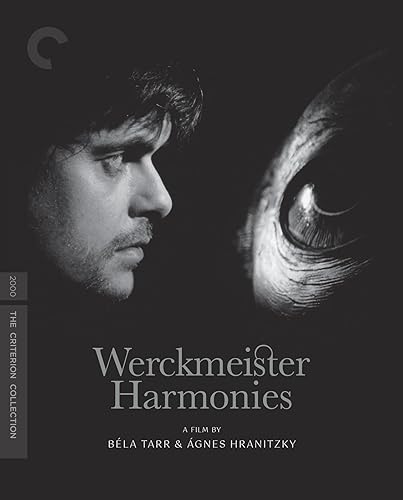

Many notable writers have adapted their own works for film or written original screenplays, but Krasznahorkai’s collaboration with Béla Tarr stands out for its singular artistic vision. The five films they created together are widely recognized as among the most accomplished in world cinema over the past forty years: Damnation (Kárhozat, 1988), Satantango (1994), Werckmeister Harmonies (Werckmeister harmóniák, 2000), The Man from London (A londoni férfi, 2007), and The Turin Horse (A torinói ló, 2011). Emory Libraries hold several of Tarr’s films on DVD, Blu-ray, and streaming.

Filmed in black and white and set mostly in small Hungarian towns, these works depict a world that is desolate and decaying, yet strangely beautiful and compelling. Shots often last several minutes, perhaps echoing the lengthy sentences in Krasznahorkai’s prose. Tarr’s striking camerawork immerses viewers in the world on screen while also creating space for reflection and foregrounding film as a medium that captures the passage of time. Alongside filmmakers such as Abbas Kiarostami, Lav Diaz, and Pedro Costa, Tarr is considered a leading figure in the movement known as “slow cinema.”

Critic András Bálint Kovács notes in his book The Cinema of Béla Tarr: The Circle Closes that Tarr’s early films focused on realistic depictions of life in Hungary and relied on improvised dialogue. It was only after he began collaborating with Krasznahorkai that he fully developed the formally daring style for which he is now known.

Krasznahorkai’s first collaboration with Tarr, Damnation (1988), also marked Tarr’s artistic breakthrough as a director, earning enthusiastic praise from critics such as Susan Sontag and Jonathan Rosenbaum. The film’s plot loosely resembles a film noir: A man has an affair with a singer and schemes to remove her husband from the picture. However, the setting—a decrepit coal-mining town—and the bleakly absurd tone transform it into something entirely new.

Tarr next adapted Krasznahorkai’s novel Sátántangó, mentioned above. Running approximately seven and a half hours, the film portrays how the inhabitants of a collective farm fall under the sway of a con man with authoritarian tendencies.

Werckmeister Harmonies, at two and a half hours, is arguably the most accessible entry point into Tarr and Krasznahorkai’s cinematic world. In it, the arrival of a circus in a small town precipitates chaos and a descent into authoritarianism.

Their final collaboration, The Turin Horse (2011), is set entirely in an isolated Hungarian farmhouse and features just three characters—a father, a daughter, and a neighbor—who contend with a violent windstorm and confront the end of their existence. The radically pared-down drama recalls the work of Samuel Beckett, yet its bleak, precisely realized, and ultimately beautiful world is distinctly Tarr’s, and Krasznahorkai’s, own.

—by Katalin Rac, Jewish Studies librarian, and James Steffen, Film and Media Studies, Theater, and Interdisciplinary Studies/ILA subject librarian