I want to start off with a personal anecdote. I grew up in an area that was predominantly white, Christian, and politically conservative in a Buddhist family and as a gay, mixed-race individual. When you grow up with people who in many ways not only are not like you, but who dislike or even hate you before they even meet you, you learn to find spaces where you will be supported–where you can be yourself. For me (and for many others) that was the library. Part of what made the library so special was finding a far wider spectrum of perspectives and ideas in books and media that I could in the community around me.

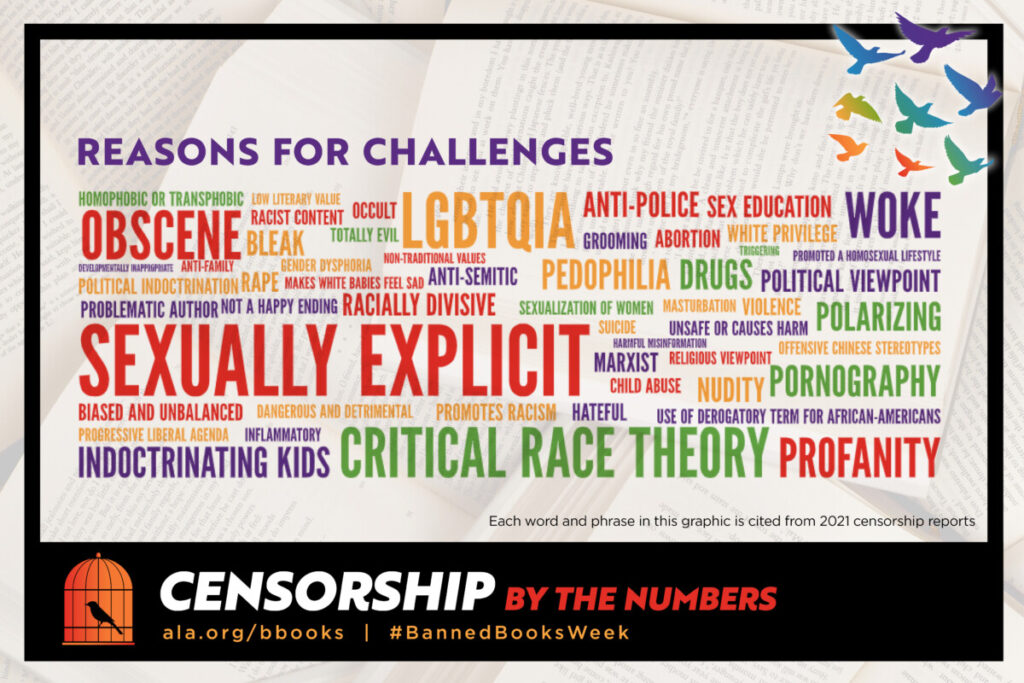

The space of the library is one that is constantly challenged. There is the recent prominent case of a school board in Tennessee banning the graphic novel “Maus” (click here to view Maus in Emory’s collection), but cases like this happen regularly across the U.S, including in Florida, Pennsylvania, and Texas. Many other states are also considering bans of varying scope and size. The American Library Association (ALA) found that the number of challenges to get books banned was at its highest since 2000.

These bans often focus on the idea of protection. They assert that the content of these books is inappropriate for the target audience. Or, in the case of laws targeting critical race theory (CRT), they assert librarians are attempting to “indoctrinate” patrons into political belief systems (this was the case with a bill in Idaho). Often, these views employ the notion of neutrality to ground their argument, as in the case of a recent New York Times opinion piece.

Librarians and community members alike have responded to these challenges in a number of ways. The ALA has information related to banned books, including how you can get involved. More broadly, we find a spectrum of activism, ranging from students protesting (and successfully overturning) a book ban to advocating on library and school boards to responses to the New York Times opinion piece.

In various ways, these responses emphasize the importance of maintaining spaces for inclusive, informed inquiry. They point out that books that are frequently challenged or banned are often from historically marginalized and underrepresented communities. They note the importance of honestly and openly discussing the injustices of the past and their implications for the present. As Viet Thanh Nguyen puts it, “Books are inseparable from ideas, and this is really what is at stake: the struggle over what a child, a reader and a society are allowed to think, to know and to question.”

Want to read some of this forbidden literature? Click the links below to check them out in Emory’s collection:

- Gender Queer: A Memoir. Maia Kobabe.

- Lawn Boy: A Novel. Jonathan Evison.

- All Boys Aren’t Blue. George M. Johnson.

- Out of Darkness. Ashley Hope Perez.

- The Hate U Give. Angie Thomas.

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian. Sherman Alexie.

- Me and Earl and the Dying Girl. Jesse Andrews.

- The Bluest Eye. Toni Morrison.

- This Book is Gay. Juno Dawson.

- Beyond Magenta. Susan Kuklin.

Looking for more banned material? Click here to check out the ALA’s annual list of most-frequently challenged books.

—by Kyle Tanaka, 2021-22 Woodruff Library Fellow and PhD candidate in philosophy at Emory University