Warning: This article contains descriptions of violence and assault.

Nov. 9–10, 2023, marks 85 years since Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass. Also known as November Pogrom, it was a wide-scale pogrom in the Third Reich that in November of 1938 included Nazi Germany, Austria, and parts of the former Czechoslovakia.

Pogrom is a Russian word for government-incited and supported antisemitic aggression against human life and property, broadly used in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to describe physical persecution of Jews by mobs. That it came to denote this series of events in Germany at the eve of World War II indicates that the concept once describing antisemitic aggression in the Russian Empire became applied internationally in the 20th century. Steven Zipperstein’s book “Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History” from 2019 explains this process. It recounts the monstrosity of the April 1903 massacre in Kishinev (today Chișinău in Moldova), which left 49 Jews dead and many injured in body and spirit and received unprecedented international attention.

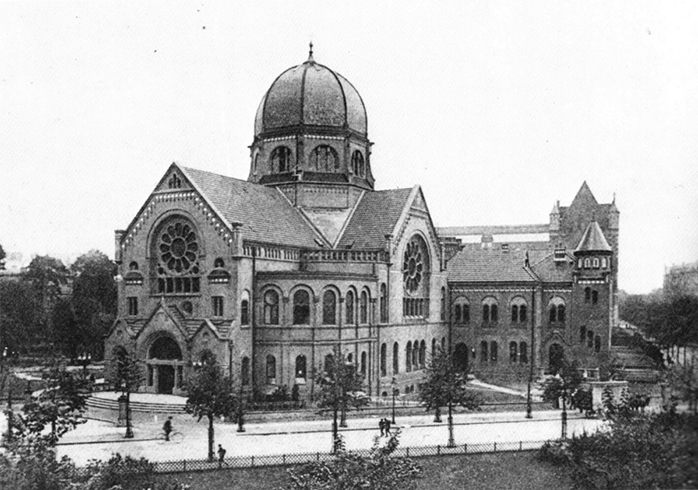

The Bornplatz Synagogue in Hamburg, Germany, which once held 1,200 congregants before it was destroyed during Kristallnacht. (Wikimedia Commons/CC 1.0 Universal/Public Domain)

Due to extensive reporting, Kishinev “became shorthand for barbarism,” notes Zipperstein, so much so that, as he quotes The New York Times journalist Peter Steinfels arguing in 1998, “Before Kristallnacht there was Kishinev.” For example, Zipperstein points out its effects on the future founders of the NAACP, William English Walling (1877–1936) and his wife, the Russian-born Stanford graduate, member of The Crowd and a collaborator of Jack London, Anna Strunsky Walling (1879–1964). They viewed lynchings as similar to pogroms. (See James Boylan’s 1998 “Revolutionary Lives: Anna Strunsky & William English Walling” in the Emory collection.) The Russian term pogrom was adopted into various vocabularies all over the world after the Kishinev massacre.

The killings and destruction of Jewish communal and private property in Nazi Germany late evening on Nov. 9 erupted as the National Socialist Party commemorated the failed Munich Beer Hall Putsch of 1923. (See the commemoration of the Viennese Neue Freie Presse, once the employer of Zionism founder Theodor Herzl (1860–1904) and Stefan Zweig (1881–1942), the world renowned novelist, from Nov. 9, 1938, available from the Austrian National Library.) The Nazi authorities explained the aggression as a justified revenge for the murder of the German diplomat in Paris, Ernst vom Rath. Herschel Grynszpan (1921–1943?), a Jewish youth of Polish origins, killed Rath on Nov. 7, avenging the expulsion of Polish Jews, his family included, from the Third Reich just a few days earlier.

The extent of the horror can be grasped by the number of deaths. In contrast to the official number of 91 victims, scholars believe that the real numbers, including concomitant suicides, were in the hundreds. Many people were beaten severely and/or raped. Additionally, about 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and most of them deported to concentration camps. In addition to the government-coordinated theft and destruction of private and communal property (from desecrated Torah scrolls, to burned synagogues, to the confiscations of insurance payouts to Jewish business owners), the Jewish community was fined for the vandalism, stressing that Jews were responsible for the massacre.

Woodruff Library houses a broad range of resources pertaining to the history of Kristallnacht. The Kristallnacht Library Guide recommends a selection of recently published resources on this annually commemorated event, including positive news – this year, for the 85th anniversary, the Bornplatz Synagogue of Hamburg, which was burned down on Kristallnacht, is being restored.

—by Katalin Rac, Jewish Studies librarian