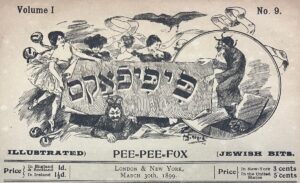

Emory Libraries is one of the ten institutions in the world to hold the full run of the Jewish magazine Pee-pee-fox, also known as Pipifoḳs (transliteration) and in Hebrew script פיפיפאקס—according to Worldcat.org. At the beginning of 2024, the acquisition of this periodical was made possible through Emory Libraries’ Davis III Humor Endowment. As of December 2024, however, Emory Digital Collections uniquely offers online access to all the 84 issues of this illustrated weekly, published between February 1899 and October 1900 in London (UK) and New York (NY). Thanks to an 11-month collaboration between colleagues working in Acquisition, Cataloging, Preservation, Digitization, Scholarly Communications, Digital Collections Management and more, as well as the support of faculty members, this periodical is freely accessible in high resolution via the internet. This campus-wide collaboration supports research and cultural preservation alike.

Emory Libraries is one of the ten institutions in the world to hold the full run of the Jewish magazine Pee-pee-fox, also known as Pipifoḳs (transliteration) and in Hebrew script פיפיפאקס—according to Worldcat.org. At the beginning of 2024, the acquisition of this periodical was made possible through Emory Libraries’ Davis III Humor Endowment. As of December 2024, however, Emory Digital Collections uniquely offers online access to all the 84 issues of this illustrated weekly, published between February 1899 and October 1900 in London (UK) and New York (NY). Thanks to an 11-month collaboration between colleagues working in Acquisition, Cataloging, Preservation, Digitization, Scholarly Communications, Digital Collections Management and more, as well as the support of faculty members, this periodical is freely accessible in high resolution via the internet. This campus-wide collaboration supports research and cultural preservation alike.

The brittle pages, barely held together in the binding that a previous steward prepared for the magazine issues, found an expert new home in Emory Libraries. Pee-pee-fox has been added to Emory collections rich in Jewish archival and newspaper holdings, Yiddish publications from Eastern Europe and the US, and literary and scholarly literature that have been supporting research and learning in a number of areas. These study areas include Yiddish—the language many East and Central European Jews spoke as first language also in the 20th century—and Yiddish literature, Jewish migration, journalism, publishing, the emergence of the modern Jewish public sphere, and the broader topic of the modern transnational Jewish experience in the US and Europe. These topics are examined in depth through courses offered to students by Emory University’s Tam Institute for Jewish Studies.

Printed in Hebrew script and intended for Yiddish readers on both sides of the Atlantic during the age of mass migration to the Americas, Pee-pee-fox attests to East European Jewish communities’ diverse modern cultural production from the late 1700s. The growth and transformation of publishing for Jewish readers in multiple languages, among them Yiddish, was central to Jewish modernity, as experts of modern East European Jewish history and Yiddish culture and literature highlight, among them Emory professor of history Ellie Schainker and the Judith London Evans Director of the Tam Institute of Jewish Studies at Emory University Miriam Udel. Pee-pee-fox also illustrates the strength of cultural ties between Yiddish-speaking Jewish communities across large geographical distances. Over three million Yiddish speakers were among the close to four million Jews who left Europe and the Middle East from the mid-19th century through the interwar period. Researchers focusing on late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Jewish history in the US, among them Emory professor of history Eric Goldstein, who particularly supported the acquisition of Pee-pee-fox, underscores that the transnational networks emerging as a result of migration not only helped develop a Yiddish public sphere in the Americas, but also made it possible for the American communities to influence the ones in Eastern Europe on the cultural, political, and economic planes alike.

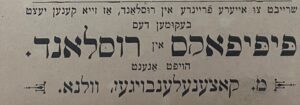

The repeated calls to make family members remaining in Eastern Europe interested in the newspaper by the well-known New York entrepreneur Judah Meir Katzenelenbogen offer additional illustration to Professor Goldstein’s research underscoring that American Yiddish publishing, which developed in a competitive market-based business environment, shaped the traditionally elite-focused Yiddish book and periodical market in Eastern Europe. (See Goldstein’s chapter “A Taste of Freedom” in the 2014 volume Transnational Traditions: New Perspectives on American Jewish History (pp. 105–139) on the connections between Yiddish publishing in the US and the Russian Empire in the last decade of the nineteenth century.) Goldstein notes that Katzenelenbogen relied on his brother, Mordechai, who ran the family’s publishing business in Vilna (p. 114), to spread American-published works in Russia, while he imported Yiddish literature from Eastern Europe to New York.

“Pee-pee-fox in Russia,” the advertisement by Katzenelenbogen

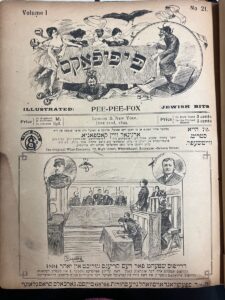

Moreover, from Pee-pee-fox’s stories, illustrations, caricatures, and picture riddles, the student of the era can understand what counted as humorous to these communities. Similarly, the magazine’s discussion of the falsely accused Jewish officer of the French military, Alfred Dreyfus, in Paris, exemplifies the serious issues that preoccupied the editor and readers who closely followed the news.

In 1899, Dreyfus was tried again and Pee-pee-fox presented an illustration of the beginning of the case in 1894 on the cover of the June 22 issue.

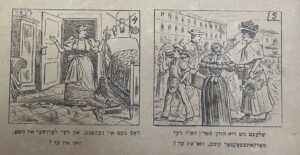

The advertisements are informative of the period’s material and visual cultures and level of Jewish integration in London and New York: the various issues document trends of fashion and hairdos and offer insights into the era’s furniture and interior design, and more.

The riddles from vol. 1, number 2.

Pee-pee-fox awaits readers and researchers exploring its stories, history, and cultural role in further depth and from new angles. Researchers and students will perhaps also consider taking up the challenge of finding the etymology of the periodical’s title—which remains an enigma to the author of this blog—and the persona hiding behind the editor’s pseudonym.

—by Katalin Rac, Jewish Studies librarian