In 2022, Making an Impression: The Art and Craft of Ancient Engraved Gemstones was the first exhibition of ancient gems in the southeastern United States. Organized by curator of Greek and Roman Art Ruth Allen of the Carlos Museum, this exhibition drew from the museum’s collection of Greek and Roman gems, many of which had never been displayed publicly. They were supplemented and contextualized by key loans that explored the material, iconography, and function of engraved gemstones in classical antiquity.

Material significance

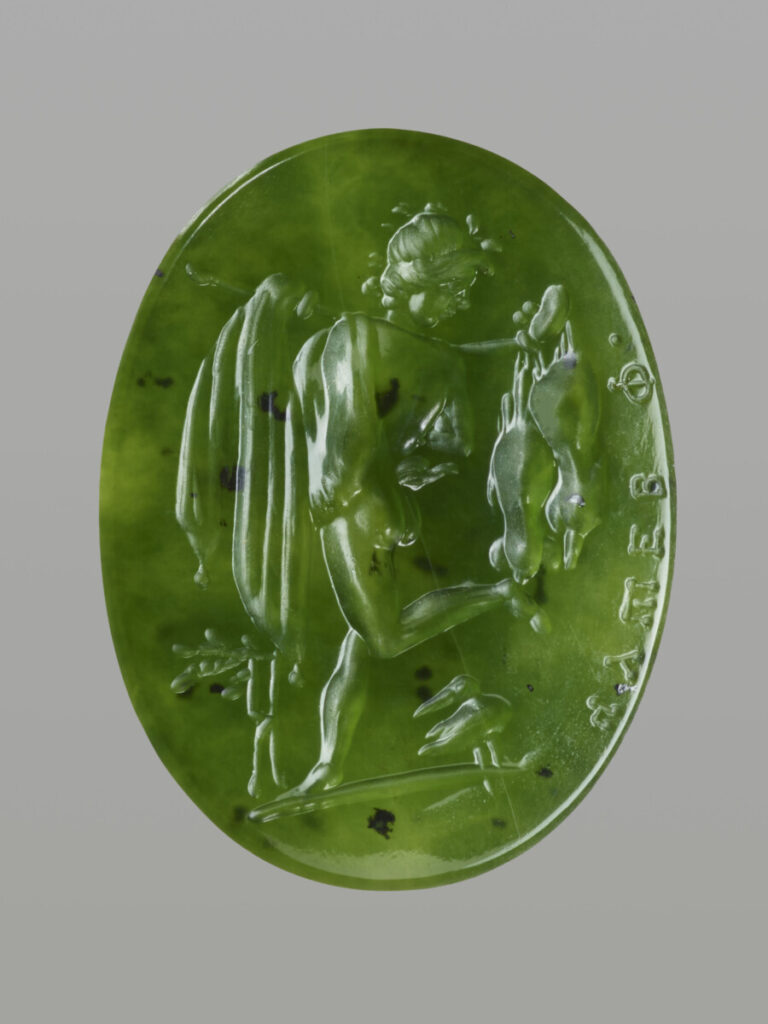

The gems were carved from semiprecious stones with miniature images of various subjects, including gods, emperors, animals, and characters from myth. Such engraved gems in the Greek and Roman worlds were typically mounted in rings and used as signets, amulets, and personal ornaments. They were admired (and problematized) as luxury artworks, treasured as antiques and heirlooms, often worn as statements of status, wealth, sophistication, and learning.

Exploring the material, production, and various functions of these small but significant ancient artworks, Making an Impression drew attention to the people who interacted with them – from the enslaved miners who quarried the stones, to the engravers who carved them, the individuals who wore them, and the viewers impressed by their luster. Whether used as seal stone, amulet, or personal ornament, engraved gems were intimately involved in the making, marking, and safeguarding of personal identity.

Despite their small size and seeming frivolity, engraved gems provided large windows into different aspects of the classical world. These include the cross-Mediterranean trade, expansion of the empire, administrative practices, expression of gender, status and wealth, the pursuit of luxury, encounters with the divine, as well as ideas about magic and medicine.

Making gems visible and accessible

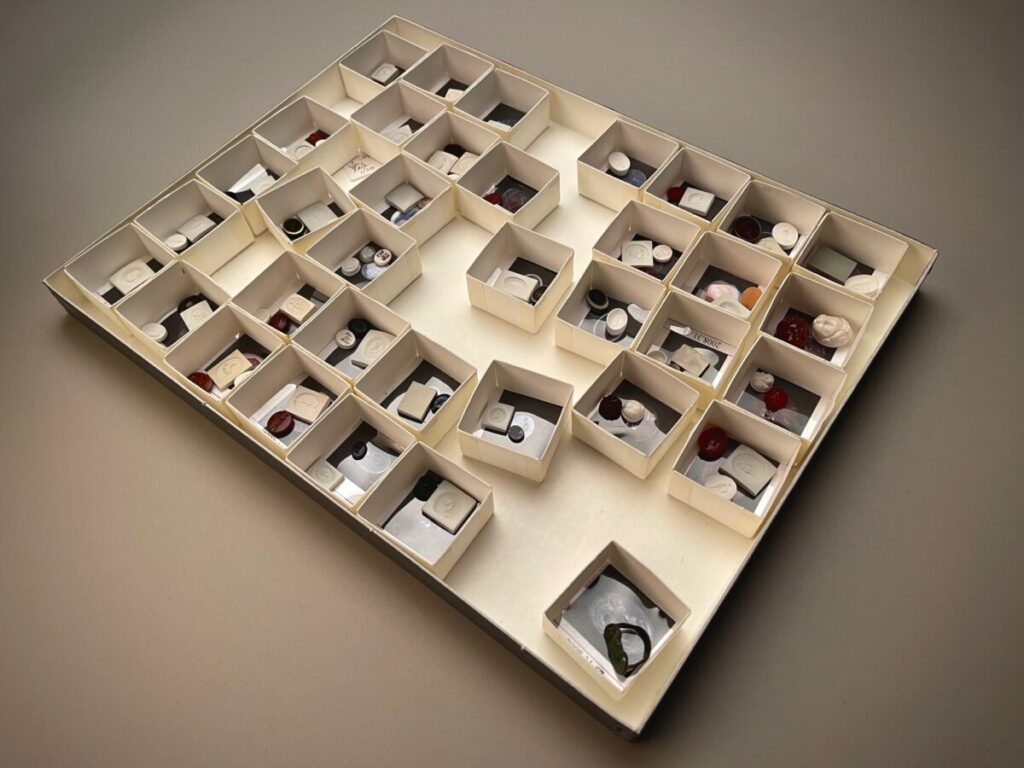

The small size, translucent material, and highly polished surfaces of engraved gems often mean that they are hard to view in a museum setting. To make the gems and their miniature engraved images as accessible as possible, the exhibition made use of digital and analogue technologies. Each gemstone was individually mounted in a shallow case that allowed the viewer to get close to the stone. They were lit with LED lights, optimally positioned for each object. Some gems respond best to backlighting while others do to raking light, and yet others to both. Visitors were given magnifying glasses to examine the gems themselves (from behind glass!). Touchscreens positioned throughout the galleries contained high-resolution photographs that could be expanded, allowing visitors to explore details further.

Once the exhibition closed in November 2022, most of the Carlos gem collection returned to storage in anticipation of a new permanent installation at the museum. The Carlos is committed to increasing the accessibility of its collections, even when they are not on display. The best way to ensure this is through updating the museum’s online collections pages with new, high-quality photographs of the entire gem collection.

Impressions from Emory Libraries digital photographer Paige Knight

In a collaboration, it always takes some time to figure out what is needed, what is a priority, and what is not. Collection stakeholders often focus on what they want from a creative project by recognizing what is not needed and building from there. The first gem that I photographed took two weeks of trial shots to achieve the correct image. After many tests and failed attempts, I decided to stop looking at the first gem in the same way. Instead, I flipped everything around and literally photographed the gem upside down. It was perfect.

Each of these little jewels is unique and literally designed for viewing a different image when light hits it from different angles. My task was to make these images visible in one photograph. This process taught me the lesson to stop approaching our project in any way that usually made sense.

This is not the type of project to create a process or follow a manual and repeatedly do the same thing with the same results. I needed to find a copy-and-paste solution, but there wasn’t one. Each gem had to be carefully observed individually, and I had to be willing to reject everything that I thought I knew – or know – to try something new. The same holds true for the post-production and editing of our final photographs.

As a first photography collaboration between Emory Libraries and the Carlos Museum, it’s been infectious to learn about the gems directly from curator Ruth Allen, feeling her excitement and hearing her appreciation for all the little gems. The final images will help to make the gems more accessible for all to see their preciousness. We hope this is the beginning of many great collaborations.

—written by:

Paige Knight, digital photographer, Emory Libraries

Ruth Allen, curator of Greek and Roman Art, Carlos Museum

Kim Norman, director of Preservation & Digitization Services, Emory Libraries