Share

Share

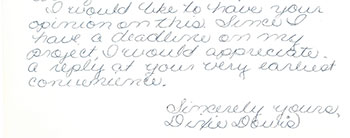

On January 23rd, 1970, Dixie Dowis, an eighth-grade student at Decatur's Gordon High School, wrote a letter to former Atlanta mayor William B. Hartsfield. In a florid hand, she explained that a school assignment required her to write to prominent Atlantans to learn what problems confronted the city in the years ahead. “Since I have a deadline on my project,” she concluded, “I would appreciate a reply at your very earliest convenience.” To his credit, Hartsfield replied within the week. Atlanta's future prospects were good, he reasoned, but only so long as the city was allowed to “grow and prosper.” However, if “people insist on moving to the suburbs and then resist the expansion of the city limits,” he warned, “this will finally effect our future government and Atlanta's future will not be bright.”

Excerpt of Letter from Dixie Dowis to

William B. Hartsfield, 1970

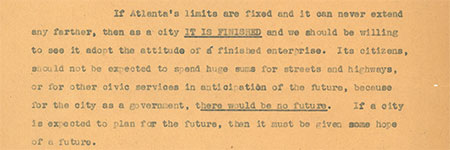

It's hard to imagine Hartsfield responding any differently. From his first term in office in the late 1930s until his death in 1971, Hartsfield remained adamant that Atlanta's future health depended on its ability to regularly expand its borders. And as his personal files at MARBL indicate, its inability to do so was a source of no small frustration. In remarks delivered before the Buckhead Civitan Club in 1941, for example, Hartsfield described annexation as a matter of existential consequence. “If Atlanta's limits are fixed and it can never extend any farther,” he began, “then as a city IT IS FINISHED and we should be willing to see it adopt the attitude of a finished enterprise.” In the pages of text that follow, Hartsfield predicted that annexation would result in greater administrative efficiency, but insisted that the issue was less a matter of tax savings than of citizenship.

Remarks by William B. Hartsfield delivered to

the Buckhead Civitan Club, 1941

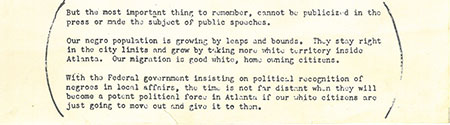

However compelling, Hartsfield's calls to civic pride were not entirely candid. As he admitted a few years later in a letter sent to select Buckhead residents, “the most important thing to remember cannot be publicized in the press or made the subject of public speeches.” In recent years a large share of Atlanta's “good, white home owning citizens” had relocated to Buckhead and other nearby suburbs upsetting the racial balance within the city limits. Without annexation, he worried, the city's black residents could become a “potent political force” in city politics. Indeed, metropolitan growth outside the city limits outpaced that of the central city as early as the 1920s, while the 1946 abolition of the white primary dramatically enhanced the influence wielded by black voters in municipal affairs. Still, for all of Hartsfield's lobbying, annexation measures languished in the state legislature until 1947 when a referendum was approved to determine whether residents in the Buckhead vicinity cared to be annexed by their larger neighbor.

Letter from William B. Hartsfield to

select residents of Buckhead, 1943

As it turned out, they didn't. Though that measure failed by a two-to-one margin, Hartsfield and his allies under the gold dome continued to press their case in the years ahead and in 1950 the state Local Government Commission produced an ambitious proposal entitled the “Plan of Improvement.” Though it was careful to avoid the term, the proposal called for the annexation of some 100,000 residents in an 82 square mile area, effectively tripling the physical area of the corporate city. The chamber of commerce meanwhile launched a public relations campaign in support of the plan and voters approved the measure the following summer.

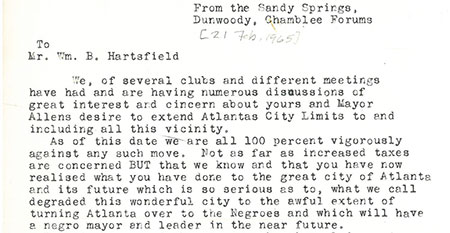

The Plan of Improvement's success must have provided a measure of gratification for Hartsfield who had spent much of the past decade campaigning for the city's expansion. As civil rights activism gathered steam over the course of the next decade and a half, however, ever larger numbers of white residents relocated to suburban communities just beyond the city limits. By the mid 1960s, it appeared that black residents would compose a majority inside the city within a few years time, a prospect that Hartsfield, current mayor Ivan Allen, Jr. and other white power brokers viewed with grave concern. With tensions simmering along racial fault lines in the nations cities, successful annexations had become exceedingly rare in metropolitan America and Atlanta was no exception. When the city next attempted to enlarge its borders by annexing Sandy Springs in 1966, residents in the affluent suburban community defeated the measure by a wide margin.

Letter to William B. Hartsfield from

the Sandy Springs, Dunwoody and Chamblee Forums, 1965

In the more than six decades since the Plan for Improvement was approved by voters, Atlanta has not undertaken a single annexation of any consequence. In fact, rather than cast their lot with the city, unincorporated communities surrounding Atlanta have taken an altogether different approach to municipal service provision. In recent years, Sandy Springs, Johns Creek, Brookhaven and others have all voted to incorporate as independent cities, a trend that critics have described as undemocratic. Hartsfield would have hated it.