by Mashadi Matabane, Graduate Student in the Institute of Liberal Arts at Emory University, and Graduate Assistant to Randall Burkett, Curator of African American Collections in MARBL

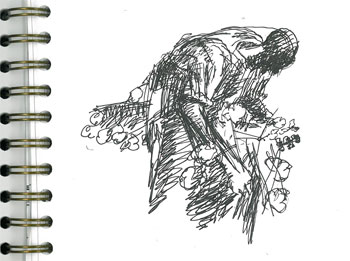

Sketch of Man Bent Over Picking Cotton,

John Biggers Papers

Dr. John Thomas Biggers (1924-2001) was a versatile American artist and art educator whose particular mix of murals and drawings made artistic appeals and references to identity, community, and Africa throughout a long career beginning in the 1940s. MARBL's acquisition of the John Biggers Papers, 1950-2001 contains a multitude of materials that demonstrate how the working life of one man ultimately created a masterful life's work.

The collection, like his legacy, is both broad and intimate in its scope. Numerous letters from influential Austrian art educator Viktor Lowenfeld reveal camaraderie between the two and, particularly, Lowenfeld's sincere investment in Biggers ongoing artistic and academic development. Biggers apprised Lowenfeld of his latest projects with letters and photographs, shared news of awards won, and exhibits scheduled. Lowenfeld provided valuable advice, contacts and connections.

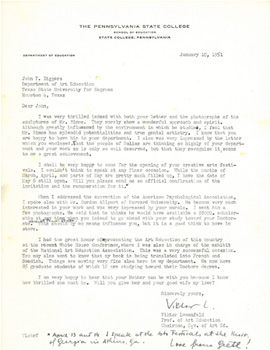

Letter from Viktor Lowenfeld to

John Biggers, January 1951,

John Biggers Papers

In a January 1951 letter Lowenfeld writes:

“When I addressed the convention of the American Psychological Association, I spoke also with Dr. Gordon Allport of Harvard University. He became very much interested in your work and was very impressed by your murals. I sent him a few photographs. He said that he thinks he would have available a $2,000 scholarship at any time when you intend to go ahead with your study toward your Doctorate. This should by no means influence you, but it is a good think [sic] to have in store.”

Initially, a professor at Hampton Institute who taught Biggers in an art class, Lowenfeld later became the head of art education at Penn State University, where Biggers eventually transferred in 1946 after a stint in the Navy during World War II. At 25, Biggers was Chairman of the fledgling art department at Texas Southern University (then called Texas State University for Negroes) in 1949.

In 1953, Lowenfeld responded to Biggers in reference to what is likely the mural, “The Contribution of Negro Women to American Life and Education,” which Lowenfeld encouraged Biggers to submit for his doctorate at Penn State.

“Dear John, My late answer is in no relationship to my enthusiasm which I have for your mural and the work you are doing. I am very impressed by the excellency of your mural. It far exceeds the mural in the Old Women's Home. I am very curious to see how you develop the part of the school and the children, or do you omit the school entirely? Do you have exact records of every stage? I told you that you need photographs of all your important sketches, especially the ones in the beginning which show the evolutionary processes of the mural.”

Funnily enough, in a March 8, 1954 letter, Lowenfeld even had something to say about the acknowledgements Biggers had written for his dissertation. He encouraged Biggers to loosen up and write “first a sentence on the meaning of Negro Art Expression which became first meaningful to you at Hampton.”

John Biggers' Sketch from

Maya Angelou's “Our Grandmothers,”

John Biggers Papers

In addition, sketches and drawings in the collection show the ongoing intercultural and international influences Biggers drew upon, in conjunction with that of Lowenfeld's support and Biggers own experiences in the United States. In 1957, Biggers made a first trip to Africa on the cusp of mass decolonization and before the continent became a major tourist attraction for African Americans. This expanded his use of symbolism and lore, which remained present in his work into the 1990s. The 1994 drawings “Rebirth,” “Morning Star, Evening Star,” and “Rape of the Earth” offer a look at the depth and detail he applied to early versions of works that inspired or eventually transformed into lithographs for a folio representing Maya Angelou's poem “Our Grandmothers.”

One notebook features a few sketches of a solitary man bent over picking cotton, a woman with a child, and a woman at work in fields. They are reminiscent of Biggers early epic narrative murals and paintings from the early- to mid-twentieth century (eras of incredibly vile racial and economic inequality). These captured the amazing grace of a bounty of black folks (rural and urban, Southern and Northern, young and old) making a way out of no way. Biggers represented who black people were to each other when they were around one other: as lovers, neighbors, family, and friends. The John Biggers papers help make clear the continued importance of his work, especially as essential to mediating understandings of that contemporary dynamic sphere of art widely regarded as…”post-black.”