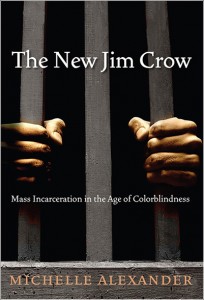

Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness is a bestselling, holistic challenge to the notion that we live in a society that has left systemic racism and racial castes behind. Her book argues why mass incarceration is essentially the Jim Crow of our generation and how hard it is to find solutions in a colorblind society. She draws many striking similarities between the legally explicit racial subversion of black Americans and the thinly veiled caste system of mass incarceration, hidden behind ‘get tough on crime’ rhetoric. Both mass incarceration and Jim Crow are characterized by racial discrimination in legal codes, exploitation, political disenfranchisement, exclusion of blacks from juries, stigmatization, racial segregation, and more. Her mission with this book was to access both the black leaders that may be unaware of the severity of this issue, and white readers who may have little to no former knowledge of either mass incarceration or the history of institutionalized racism in America. She wanted to promote awareness, and incite a social revolution of activists who can find everything they need to know in one 260-word book. In this mission, I believe she was successful, save one thing that seemed to be missing.

The first thing that Alexander draws attention to is how black exceptionalism is used as an excuse that there is no longer racism integrated in our system. Alexander does an excellent job picking apart the issues with black exceptionalism, and how detrimental that line of thinking really is to Black America. Alexander draws attention to racist policies and campaigns such as the push to “get tough on crime” and the “war on drugs.” Presidents Nixon, Reagan, and Clinton pushed these campaigns forward. This “war on drugs” was, Alexander argues, a reincarnation of the racial caste systems in America. Politicians cited “welfare queens” and the “crack cocaine epidemic” as thinly veiled racism intended to drive images of black criminality and laziness into the minds of the American public. They used this momentum to create absurd drug penalties and one- or three-strike policies to imprison black men and deny them and their families federal assistance.

While many sources can give you the facts that are thrown out back-to-back in The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander’s most uniquely effective tool was delving into what real life looked like for black people who become victims of the criminal justice system. Alexander shows how the cards are stacked against young black men the second they fall into the trap of incarceration, and takes the reader through what life is like for ex-convicts. She amasses so many stories, court cases, and individual accounts, woven into her description, making it all the more real. This is incredibly effective, because it is much easier for people to maintain a cognitive separation between these institutions and the real lives and communities that they are destroying without personal accounts and examples. Once the issue is humanized, it is difficult to resist feeling outraged, and wanting to drop everything to make a change. This is what helps Alexander effectively engage the wide audience, and craft “the bible of a social movement,” as the San Francisco Chronicle called it.

The only critique to give The New Jim Crow falls is that it falls short in one aspect. She never outlines any concrete or potential ways to fix mass incarceration. Short of even the major fixes, Alexander doesn’t provide a now motivated and outraged readership a way to get involved or make a change. Alexander does show the difficulty of solving mass incarceration, by showing Supreme Court decisions that permit systematically violating our rights. However, writing as in an action oriented way is an extremely important part of any social justice book.

Throughout The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander carefully chips away at our recent and long-term history, until the reader watches their image of America crumble. This is, I believe, one of the most important purposes of this book: to see history from the perspective of the oppressed. She exposes the reality in a brilliant way, never losing her audience to claims that are too bold or that jump to the conclusion too quickly. Instead, Alexander guides the reader to reach this inevitable conclusion organically; that the America of the past and present has suppressed black people since they first arrived, and has been doing so since long after the history books tell us it ended.