The Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace is one of the most complex and evocative sacred landscapes of ancient Greece. Visitors of today might feel a strong intuition that the place is special, as Dr. Bonna D. Wescoat (Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Art History at Emory University and Director of American Excavations Samothrace) explains, but they find it challenging to reimagine how it all fit together in antiquity. The Archaeological Museum of Samothrace offers such an opportunity to visualize the past, with the aid of 3D modeling by the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS). The Samothrace museum has announced its temporary re-opening of Hall A after years of renovation, and in the 3D model included in the exhibit and on the American Excavations Samothrace website, ECDS Visual Design Specialist Ian Burr has helped reconstruct the ancient landscape and the ancient buildings of the sanctuary. The video follows the path of the ancient visitor through the site. From this model, viewers are able to form a much richer understanding of why the Sanctuary was one of the most important and beautiful Hellenistic religious centers of Greece. Being able to see the video in the Museum will allow visitors to experience the ancient site with greater awareness and also allows viewers to experience the Sanctuary from afar.

- Video: The Sanctuary of the Great Gods – 3D Model (early 1st cent. AD)

- American Excavations Samothrace: https://samothrace.emory.edu/

The Archaeological Museum of Samothrace, designed by Stuart M. Shaw of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, was constructed between 1939 and 1961 and renovated in 2014-2015. The first exhibition in the Museum was opened in 1955. The new exhibition, which is in preparation, consists of Halls A, B, C, D, and E. In the portico of the central courtyard between Halls C and D, inscriptions mostly from the Sanctuary are exhibited; Halls C and D are dedicated to the Sanctuary of the Great Gods under the respective titles Entering the Sanctuary and Initiation. In Hall A, architectural features of major buildings of the Sanctuary have been reconstructed. Hall B is dedicated to the ancient city and its Nekropoleis, while the last Hall E contains finds from the island outside the Sanctuary of the Great Gods which date from the Middle Neolithic period (ca. 5500 BC) to modern times (19th century).

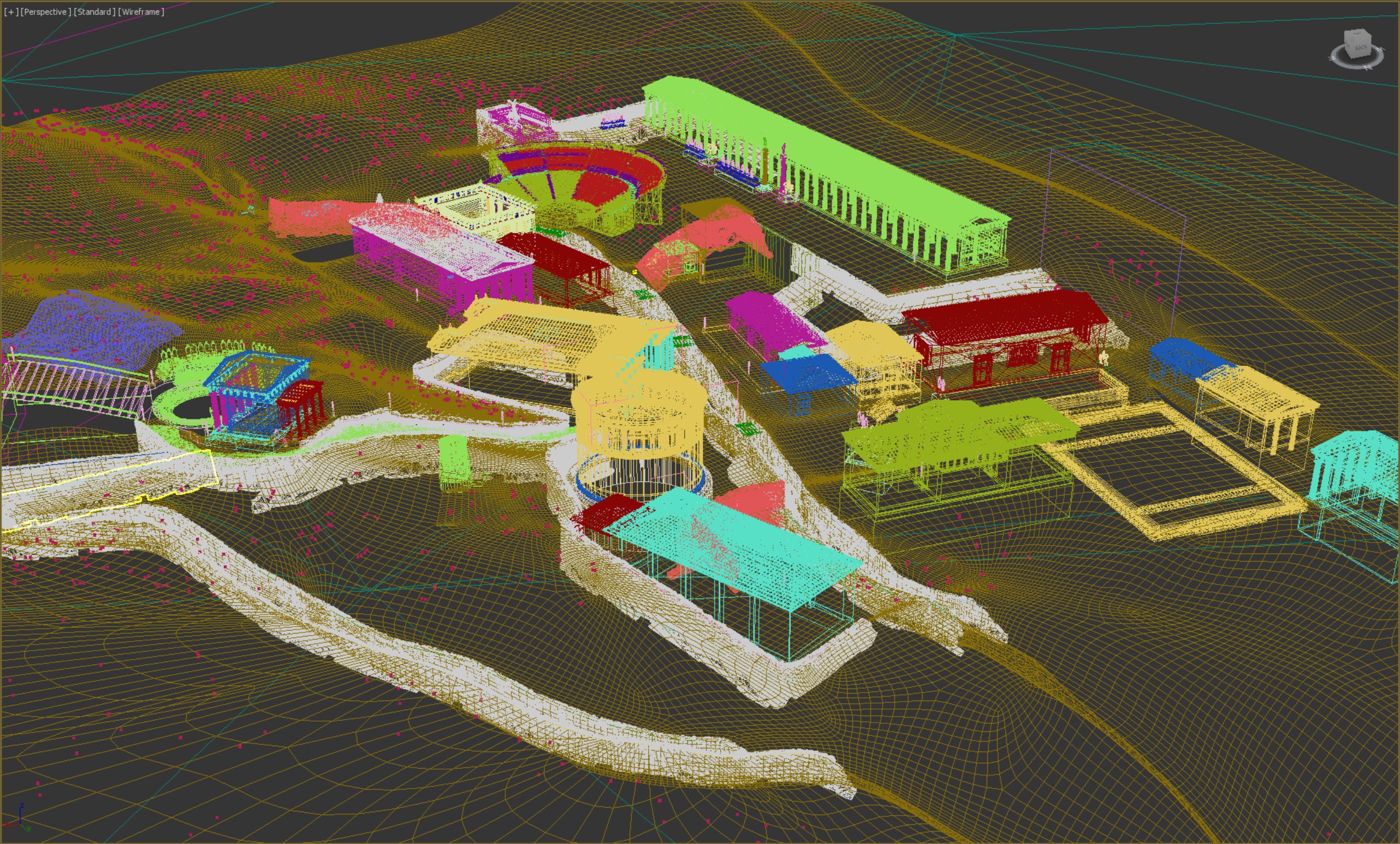

Hall A reopened recently on August 14, which was—as archaeologist Dimitris Matsas explains—on “the eve of a diachronically great festival on the island, celebrating the Dormition of the Virgin.” The new video includes several overlays of the 3D model on a photograph of the surviving remains of the building. The three featured buildings in the video and Hall A (with reconstructions of their typical sections) are the Rotunda of Arsinoe II, the Hieron, and the Altar Court, three major Thasian marble Doric buildings.

Ian Burr—whose 3D renderings of Samothrace have been featured on the cover of Excavating Pilgrimage: Archaeological Approaches to Sacred Travel and Movement in the Ancient World (Kristensen and Friese, 2020) and the October 2020 issue of the American Journal of Archaeology—comments that while the Sanctuary of the Great Gods in Samothrace is partially well-preserved, a combination of natural forces and appropriation of stones for other purposes has reduced most of the structures to their foundations. “The video for Hall A provides an opportunity for visual storytelling to fill in the gaps, allowing visitors to the sanctuary to experience the space as an ancient pilgrim could. 3D walkthroughs trace the path of a prospective initiate: entering the sanctuary from the ancient city by torchlight, winding down the sacred way to the heart of the temple complex, and surveying the whole of the site from the Stoa hill near the famous Winged Victory statue. Photographs of the whole sanctuary as well as the three featured buildings of Hall A are shown in present state, then faded into renderings of the model. The hope is that the pairing of ruin and reconstruction will orient the viewer in the space and provide a deeper understanding of the original architecture of the buildings.”

To assemble the animations, photographs, and overlays, the American Excavations Samothrace team worked with a new partner, Konstantinos Tzortzinis, the Digital Media & Website Specialist for the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. The collaboration was so successful that the team plans to develop additional videos with him in the coming seasons.

While the team created the video primarily for the reopening of Hall A, it is also an important resource—particularly during the pandemic—for sharing knowledge of the Sanctuary of the Great Gods with audiences that are not able to visit Samothrace. Creating the 3D reconstructions, animations, and overlays and sharing them on the Samothrace website has been an important means of highlighting the importance of the Sanctuary to diverse audiences across the world.

Dr. Bonna Wescoat adds that the 3D model is also a highly sophisticated forensic platform through which users can explore how architecture, landscape, and the pathways for the ancient visitor were manipulated to heighten the sacred experience. We can investigate the importance of sightlines, for example, of the famous Winged Victory of Samothrace (also known as the Nike of Samothrace), and we can confront—in three dimensions—some of the most challenging issues facing our understanding of the development of the site over the many centuries during which it was active.

To view the video, please visit the Samothrace website’s blog post and/or view on Vimeo (via the American School of Classic Studies at Athens). You can learn more about American Excavations Samothrace on their website (created in partnership with ECDS).