This reflection post is part of a series by staff members of the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS) who have taught remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dr. Jesse P. Karlsberg is a Senior Digital Scholarship Strategist at ECDS.

Emory University students—who hail from across the country and around the world—often arrive on campus knowing little about our city and its region. “Atlanta in American Music,” the course that I taught virtually in Fall 2020, uses the metropolitan region as a case study to introduce students to key social contexts—race, class, gender, and place—that impact American music’s meaning. Motivated by Emory’s emphasis on the university’s relationship to our home city, I also designed the course to help students learn about Atlanta’s history and the issues the city faces today.

Emory University students—who hail from across the country and around the world—often arrive on campus knowing little about our city and its region. “Atlanta in American Music,” the course that I taught virtually in Fall 2020, uses the metropolitan region as a case study to introduce students to key social contexts—race, class, gender, and place—that impact American music’s meaning. Motivated by Emory’s emphasis on the university’s relationship to our home city, I also designed the course to help students learn about Atlanta’s history and the issues the city faces today.

I was surprised how meaningful it was to be focused on Atlanta while Zooming with students this fall who were scattered across the country and around the globe. Our navigation of the coronavirus pandemic, the mass protests following the killing of George Floyd, and an acutely impactful election season also brought the course’s social contexts into sharp relief. Our course’s exploration of our city, and of racial justice, white supremacy, contestation of gender roles, and prison reform, refracted through Atlanta music and its reception, became more personal in this context, and more challenging and ultimately rewarding to analyze.

Atlanta, Remotely

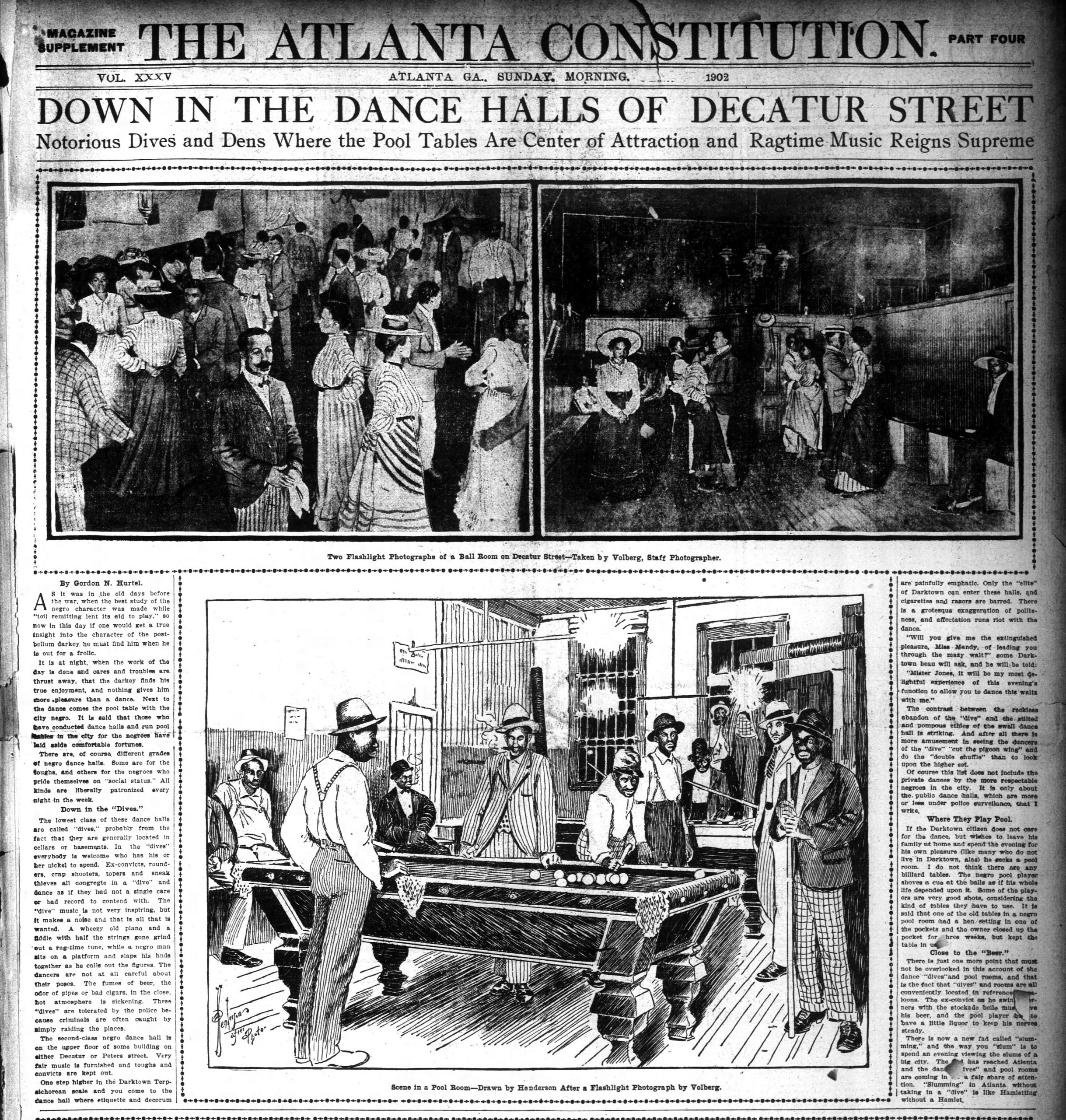

“Atlanta in American Music” introduced the city’s history, from its founding as a railroad terminus to its present as an international metropolis. We discussed the city’s neighborhoods and its shifting relationship to the broader metropolitan region. Delving most deeply into 1) the politics of early twentieth-century Atlanta and its blues, hillbilly, gospel, classical, and operatic music, and 2) the city’s history from the 1980s to the present with its hip-hop, R&B, trap, queer and alternative, and art music scenes, we examined how music animated debates about racial and economic inequality, white supremacy, gender roles, queer sexuality, and Black political power.

Emory’s mostly virtual fall semester disrupted my plan for engaging with Atlanta as a place. I had planned for students to take field trips to Eddie’s Attic, the famed singer-songwriter venue in Decatur, and rapper T.I.’s Trap Music Museum in Atlanta’s English Avenue neighborhood. I designed the course’s final project—which involved developing a driving or walking tour that would explore a facet of music in Atlanta using the ECDS open-source software platform OpenTour Builder—imagining that students could visit potential tour stops in person.

Though I feared the shift to virtual learning would make the city feel less vital, studying specific places in Atlanta felt more pressing and meaningful while we were away from the city. Several students cited the chance to spend time thinking and learning about Atlanta as their primary reason for enrolling in the course. I found students to be even more engaged than usual when our class discussed city neighborhoods or historical issues in Atlanta’s politics.

Spending time thinking critically about Atlanta every week while being offsite was also a melancholic experience. The course’s city-centric topic highlighted the difficulty of being apart and away from Atlanta and each other.

Race in Atlanta, Then and Now

In the early twentieth century, Atlanta was a booming New South City. Even though the Ku Klux Klan exerted a huge influence on civic life, Black business and cultural leaders, women, and Black and white working classes still saw and created potential new opportunities for advancement and security. Atlanta’s white business and political elite, anxious about their status atop the city’s social and economic hierarchy, imposed racial segregation and embraced white supremacist thought in order to drive a wedge between working class white and Black Atlantans. Atlantans expressed their need for opportunities, engaged in battling over and within social hierarchies, and sought to allay their anxieties through music.

By the late twentieth century, Atlanta had become an internationally recognized metropolis, but racial and economic inequality continued to grow. The election of Atlanta’s first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson, ostensibly signaled the rise of Black political power; but the “Atlanta Way”—an alliance between Black politicians and the historically white business elite—continued to leave out Atlanta’s poor Black residents. White flight, “Olympification,” and Reaganomics all contributed to continuing lack of investment in poor Black neighborhoods. Musicians ranging from acts associated with the Dungeon Family to contemporary trap artists emerged from these very neighborhoods, however, imagining alternative futures and offer searing critiques of these politics and policies.

We delved into these issues through the music of a wide range of artists, including Bessie Smith, Fiddlin’ John Carson, Thomas Dorsey, Goodie Mob, the Singing Peek Sisters, Janelle Monáe, and Lil Baby. Meanwhile, the United States had erupted into what is perhaps the largest protest movement in support of Black lives and against continuing racial injustice, and the country mobilized for a history-defining election against the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic. Race and politics were at the center of this course when I last taught it in 2018, but these same topics felt especially raw this time around.

The course was at times challenging, even emotionally exhausting. We examined Atlanta’s history of white supremacists, like John Carson, and racist lyrics, like those to his “Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane.” We also analyzed more recent music videos, like Childish Gambino’s “This Is America,” which depicted and critiqued the killing of Black people.

Watching and listening to these songs and discussing them with students made me revisit why I teach what I teach. Because the course delved deep into difficult material and explored varied shades of racism in Atlanta’s musical and political history, we approached these conversations with an extra awareness of how difficult these discussions might be. The context of heightened political and racial tensions added to the potential challenge of engaging this material, especially for students whose identities have made them historically and currently vulnerable to discrimination. Our class’s interpretation of the city’s and the nation’s race relations and electoral politics was further complicated by perspectives of international students encountering America’s race relations and political system through a comparative lens based on their own experiences.

Navigating these challenges was harder in the context of remote learning, where technologies might interfere with the ability to read each other’s emotions, and checking in with students required more deliberate effort. I was surprised, though, with how well we adapted to these circumstances, and found it was easier to read the (Zoom) room as we got to know each other despite our virtual interface. When we made space in break-out rooms and as a class to talk about how the intersections of course materials with the contemporary context impacted folks, it opened up some of the most meaningful connections I’ve had over Zoom. The value of this space was most striking to me when we met early in the afternoon the day after election day, hours after then-president Donald J. Trump had erroneously declared victory but before state counts had made clear that Joseph R. Biden was likely to win. I had already planned to go light on the course material for that session, focusing on giving students space to say how they were processing the news and uncertainty. Even with this plan, having the week’s listening assignments and course’s framework at hand proved a resource in placing our current moment in meaningful context. Remote teaching made it challenging to connect, but the extra work this demanded of me and my students ultimately brought us closer together as a class.

Conclusion

Teaching about music in Atlanta during this semester was difficult, but I also found it to be exceptionally rewarding. Talking about racial politics in the fall of 2020 was an especially fraught and humbling exercise. It was also a great privilege to work through these issues with my students. Our course provided a valuable space in which to process our values and our relationship to Atlanta during a challenging and extraordinary time: apart from one another and the city and yet, surprisingly, together.