by Murray Sternberg

The Grand Canyon, one of America’s most recognizable landmarks, is a feature of great geomorphic and cultural significance. Geologically, it formed through deposition of igneous and metamorphic rocks that were uplifted and then eroded by the rushing Colorado River (National Park Service, 2023a). As a World Heritage site, the Grand Canyon’s 1,218,375 acres receive a designation acknowledging its outstanding natural and cultural value (Historic Environment Scotland, n.d.; National Park Service, 2018b). Given the fact that the oldest rocks in the canyon are 1.8 billion years old, human uses and conception of the site have only occurred relatively recently in geologic time (National Park Service, 2023a). However, this hasn’t stopped it from becoming a cultural landscape in which its natural features and the ways they’ve evolved have been impacted by humans.

Before delving into cultural features, it’s important to consider the Canyon’s spatial boundaries, over which there has been significant controversy. Throughout its history, attempts to designate the area as a National Park have been fought by ranchers, miners, and local business owners not wanting their enterprises to be restricted in favor of tourism or conservation (Clark, 2019). A 1993 ruling by the Department of the Interior determined the boundary of the Grand Canyon to be a quarter mile from the bank of the river, while the Navajo Boundary Act (1934) sets the boundary right on the southern bank of the river (Kuhney, 2014). Although conflict has existed between the Navajo Nation and the Park Service about park boundaries, the issue hasn’t been evaluated in court (Kuhney, 2014). These types of land-use conflicts around federal environmental protections, industry, and Native groups aren’t restricted to just this one area, and have been in the news recently due to similar controversy at Bears Ears and Grand Staircase Escalante National Monuments in Utah (Siegler, 2022). Through the lens of cultural landscape studies, the area in and near the canyon can be defined as a functional region recognizing the importance of the canyon as a centralizing factor, with the importance of the land decreasing away from this central point.

Anasazi, or the Ancestral Puebloan people, lived in and near the Grand Canyon region around 10,000 years ago, and are believed by archaeologists to be the first ancient group to live in the area (Terrill, 2019). Eleven present-day Native American groups have ties to the Grand Canyon, and many of their oral histories involve the creation of the canyon in some way (National Park Service, 2022). For example, the Hopi people associate deep cultural meaning with the canyon’s geography. Some Hopi clans identify their place of emergence as being within a dome in the Grand Canyon, which is symbolic of its cultural significance (Biggs, n.d.). Hopi mythology holds that the canyon was built when two brothers threw lightning bolts and piled mud to craft the canyon’s walls and the river that flows through it (Biggs, n.d.). In this way, the Grand Canyon can be seen as an ethnographic landscape encompassing a highly meaningful heritage resource for the Hopi and other people.

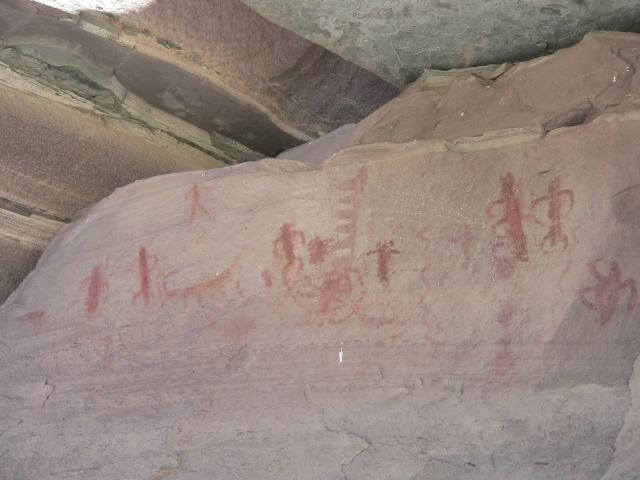

The walls of the canyon contain pictographs and petroglyphs, crucial evidence of past conceptualizations of this cultural landscape that can still be viewed today (National Park Service, 2018a; Ruland, 2022). In this way, the canyon is a vehicle for cultural exchange in which present-day visitors are able to see early understandings and artistic forms of expression associated with the landscape.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, various hydrologists and geologists have posited their own theories of how the canyon was formed (National Park Service, 2023a). The stories presented by these practitioners of Western science can similarly be considered within the framework of cultural landscape studies as a continuing landscape due to its active social role within contemporary society.

Throughout the past century, there have been many attempts by Western settlers to develop and engineer the Colorado River through the construction of dams (Robbins, 2019). Dams and water diversions to support urban and agricultural infrastructure such as the Glen Canyon Dam have caused the river to drastically reduce its flow, and reservoirs that formed as a result of dam construction have had a lasting impact on the hydrology of the Colorado River (Bureau of Reclamation, 2023; Zielinski, 2010).

Marks around reservoirs up to 70 feet above the water level, colloquially known as bathtub rings, show previous water levels, which water officials warn the water may never reach again (Zielinski, 2010). In 1923, a survey party made recommendations to dam the Grand Canyon itself, although the recommended dams were never built due to national opposition from the conservation movement (Boyer & Webb, 2007; Clark, 2019). Water engineering politics still pervade this cultural landscape, with the federal government canceling two nearby hydroelectric projects in 2022 and advocacy work being done to protest another nearby dam proposal (Grand Canyon Trust, 2019).

Although development of the Colorado has impacted the Grand Canyon area, preservation has also played a key role in its cultural history. The Grand Canyon brought people together for the sake of environmental conservation, attesting to its creation of a shared cultural history. Evidence of the Canyon’s status as a cultural landscape can be seen through its classification by the National Park Service as the Grand Canyon National Park, a designation which seeks to preserve its natural and cultural resources and values (National Park Service, 2023b). Famed American naturalist and author Aldo Leopold described the Colorado River’s ecosystems and advocated for wilderness preservation, which was instrumental in the Grand Canyon’s protection as a National Park (Lorbiecki, 2016; Robbins, 2019). The conflict between preservation and the aggressive engineering of Western natural resources in the past century can be interpreted through the theory of environmental determinism (Alexander, 1999). The Grand Canyon has controlled nearby human development and activities, through its status as a powerfully sacred place for Native groups and through its involvement in Western water politics.

Bibliography

Alexander, D. E. (1999). Environmental determinism. In Environmental Geology (pp. 196–197). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-4494-1_112

Biggs, P. (n.d.). Hopi. Nature, Culture and History at the Grand Canyon. Retrieved October 27, 2023, from https://grcahistory.org/history/native-cultures/hopi/

Boyer, D. E., & Webb, R. H. (2007). Damming Grand Canyon: The 1923 USGS Colorado River Expedition.

Bureau of Reclamation. (2023, May 19). Glen Canyon Dam. Bureau of Reclamation. https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/crsp/gc/

Clark. (2019, March 9). Border Wars. Grand Canyon Trust. https://www.grandcanyontrust.org/advocatemag/spring-summer-2019/border-wars

Grand Canyon Trust. (2019, September 30). Little Colorado River Dam Proposals. Grand Canyon Trust. https://www.grandcanyontrust.org/little-colorado-river-dam-proposals

Historic Environment Scotland. (n.d.). What is a World Heritage Site? [Historic Environment Scotland]. Retrieved October 27, 2023, from https://www.historicenvironment.scot/advice-and-support/listing-scheduling-and-designations/world-heritage-sites/what-is-a-world-heritage-site/

Kuhney, J. (2014, September 3). Dispute over land rights could sink Grand Canyon Escalade project. The Arizona Republic. https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/arizona/2014/09/04/grand-canyon-confluence-land-rights/12992581/

Lorbiecki, M. (2016, August 7). Aldo Leopold’s legacy on our national parks. Oxford University Press’s Academic Insights for the Thinking World. https://blog.oup.com/2016/08/aldo-leopold-national-parks/

National Park Service. (2018a, February 1). Why were the Petroglyphs made? Petroglyph National Monument. https://www.nps.gov/petr/learn/historyculture/why.htm

National Park Service. (2018b, July 16). Nature. Grand Canyon National Park. https://www.nps.gov/grca/learn/nature/index.htm

National Park Service. (2022, February 18). People. Grand Canyon National Park. https://www.nps.gov/grca/learn/historyculture/people.htm

National Park Service. (2023a, February 15). Geology. Grand Canyon National Park. https://www.nps.gov/grca/learn/nature/grca-geology.htm

National Park Service. (2023b, October 20). What We Do. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/index.htm

Robbins, J. (2019, February 14). Restoring the Colorado: Bringing New Life to a Stressed River. Yale Environment 360. https://e360.yale.edu/features/restoring-the-colorado-bringing-new-life-to-a-stressed-river

Ruland, M. (2022, September 29). Think the Grand Canyon is “wild”? Grand Canyon National Park Trips. https://www.mygrandcanyonpark.com/park/faqs/native-american-tribes/

Siegler, K. (2022, August 24). Utah sues to stop restoration of boundaries at Bears Ears, Grand Staircase monuments. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/08/24/1119310929/utah-sues-to-stop-restoration-of-boundaries-at-bears-ears-grand-staircase-monume

Terrill, M. (2019, February 25). Native American view of the Grand Canyon’s centennial celebration. ASU News. https://news.asu.edu/20190211-discoveries-how-native-americans-view-grand-canyons-centennial-celebration

Zielinski, S. (2010, October). The Colorado River Runs Dry. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-colorado-river-runs-dry-61427169/