The River Beneath the City

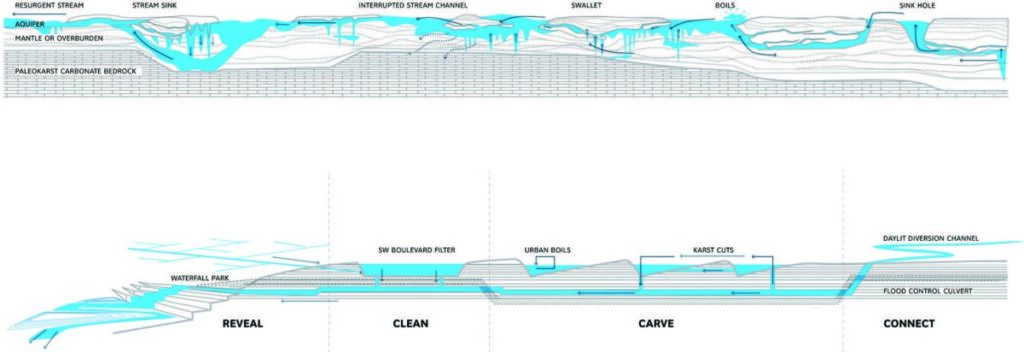

The influence of humans on nature (and nature on humans) is embodied by the urban karst landscape of Lexington, Kentucky. “Karst” refers to the system of underground limestone passageways hollowed out over millennia by streams and percolating rainwater. These features traverse nearly a quarter of the state, occasionally making themselves visible at the surface in the form of sinkholes, boils, and streams (University of Kentucky). What may be less obvious – particularly in an urban setting – is that karst provides the foundation for Lexington’s cultural identity as well as its physical structures.

Early settlers in Kentucky were eager to site their homes and distilleries near karst springs. The Blue Hole at McConnell Springs Park provides one example; it was here that the city of Lexington was first named (City of Lexington). Kentucky’s famous bluegrass horse ranches owed some of their prosperity to apatite, a mineral byproduct of limestone dissolution (Lee et al., 2017). And as populations continued to grow, Town Branch, a tributary of Elkhorn Creek, supplied fresh water to the city’s residents (Town Branch Water Walk).

Urbanization obscures the unique features of karst while simultaneously exacerbating the risks that it poses to structures and human health. Cover-collapse sinkholes are the most notorious hazard associated with karst, though it is rare for one to develop overnight (University of Kentucky). Building structures on top of previously filled sinkholes can lead to a second collapse (University of Kentucky). Additional risks of karst include exposure to radon and groundwater pollutants (University of Kentucky). This calls for careful regulation within and beyond Lexington, as the limestone passageways are intricately connected and it is difficult to predict where a pollutant will end up once introduced to the aquifer.

In recent years Lexington has been working to make karst more visible in the fabric of the city. Town Branch, once culverted beneath the city’s Main Street, is now the jewel of Lexington’s downtown park and trail system. Visitors are treated to waterfalls, channels, and karst windows that pay homage to the natural topography of their surroundings (Town Branch Park). The park’s design coincides with recent trends in environmental thought, particularly the blurring of what is “urban” and “natural.” Cities are becoming increasingly reliant on their local ecosystems as climate change threatens precious resources and human life. Many, like Lexington, are taking advantage of their unique ecosystems in order to rise to the challenge.

Grace Regnier

Bibliography:

- University of Kentucky. (2023). Karst. Kentucky Geological Survey. https://www.uky.edu/KGS/karst/index.php.

- City of Lexington. (2023). McConnell Springs Park. Lexington city website. https://www.lexingtonky.gov/mcconnell-springs-park.

- Lee, B., Carey, D., and Jones, A. (2017). Water in Kentucky: Natural History, Communities, and Conservation. United Press of Kentucky. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1pd2kxw.

- Orff, K., Wirth, G., and Weber, A. (2015). “The Deep Section: Karst Urbanism in Town Branch Commons.” Oz 37, no. 9. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6b6b/392f7eaa2ea0e5ffd64c3621467fdaeb5aa8.pdf.

- Town Branch Water Walk. (n.d.). History. Town Branch Water Walk. https://www.townbranch.org/tbww/history.html.

- Town Branch Park. (n.d.). Town Branch Park Master Plan. Town Branch Park. https://www.townbranchpark.org/masterplan.