Hong Kong’s colonial past has shaped the norms that the population adheres to. One can see that cars are driven on the left side of the road and even tailored clothes worn by people are of Western style, as opposed to Eastern. However, when it comes to the use of English, one would find that people who hail from a specific economic status and those who belong to a specific profession mostly speak it, over Cantonese. So, despite English being the second official language of Hong Kong, its use is limited to certain districts. To bolster my argument, I will utilize store signs and the normal dialogue conducted between people to compare how the use of English differs between both districts.

Upon exploring Central, I found that the use of English is rooted in commercial reasons, given how the district is a commercial hub, which is a home to many high-end western outlets. Companies such as Omega have an established image due to their prominence worldwide and are more likely to be recognized by their brand names, even by those who are not fluent. Since these companies cater to foreigners as well, having their names in Chinese might not make their stores immediately recognizable to tourists and other foreign visitors. So, it is commercially viable for these companies to have their names in English, as opposed to Chinese.

In addition, the use of English by high-end brands also implies that being fluent in the language is a sign of affluence. Apart from foreigners, most of the local residents visiting these stores can be heard conversing in English with each other and with the sales people. While the residents of Hong Kong generally speak in Cantonese with one another, it is a common sight to see them speaking in English in these stores. This is noteworthy since these brands target people of a certain economic standing, as opposed to the general public. So, having employees who are fluent might also be a way to reinforce this notion.

On the other hand, there are Western firms in Central that utilize both English and Cantonese to seem more approachable to the general public. For instance, banks like Citibank have their signs in both English and Chinese. Citibank also has representatives outside its branch who hand out pamphlets in both languages. The reason for doing so can be explained by by whom the Citibank’s consumer base is. Since these banks want to have as wide of a client base as possible, it is in their best interest to seem approachable to people of different economic backgrounds.

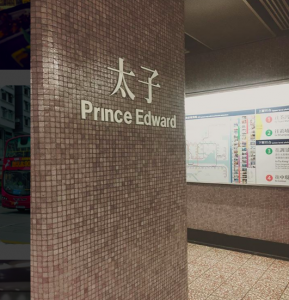

While the use of English in Central is attributed to its nature as a commercial hub, the prominence of Cantonese in shop signs and dialogue in the Eastern district is attributed to its nature as an Industrial area. Areas such as Quarry Bay are home to many Manufacturing plants, so it is not area most foreigners would prefer to live near or even conduct business. Despite many hotels present in this area, residents of the city mostly inhabit the area. So, the area consists of establishments whose signs and menus are exclusively in Cantonese. They cater to locals as opposed to foreigners and thus do not have an incentive to invest in making their restaurants more approachable by foreigners.

Side by side, the nature of these stores also explains the lack of verbal English in the area. The employees are not fluent in English and will normally resort to utilizing hand gestures and images to convey what they are trying to say. What is interesting is that most of these stores are smaller than the ones found in Central, which indicate that they are likely to be family owned businesses. Furthermore, these people can be seen working multiple jobs at a time. An instance of this was when I saw waiter working as a construction worker a few days after I had visited his restaurant. So, apart from having to target a limited consumer base, the people of the area are also not fluent in English due to their less affluent backgrounds.

So, in conclusion, it can be stated that the use of English in Hong Kong is contingent upon economic and social factors, as opposed to being based on the city’s colonial roots.

Citations

Leeman, Jennifer, and Gabriella Modan. “Commodified language in Chinatown: A contextualized approach to linguistic landscape.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 13.3. (2009).

figure.1.

figure.1. figure.2.

figure.2.