Aashna Goel

LING 343

Ireland has historically been a country of emigration, rather than immigration, with patterns of population outflows both in colonial and postcolonial times to Britain, North America, Australia, New Zealand and elsewhere. For, although immigration to Ireland came later than to neighbouring European countries, Ireland in general and Dublin in particular have historically been sites of considerable population diversity. Its geographical position as a coastal city has meant inevitable population flows since at least the eleventh century. And, whilst the industrial revolution did not have an impact on Dublin in the same way as other European cities, Dublin’s status as a university city and as a centre for public administration has led to a more heterogeneous population profile than elsewhere in Ireland. The Irish language, for instance, is spoken along the west coast and in other areas of Ireland, and most rural areas of Ireland are now affected by mobility and migration. Yet Dublin is a concentration of many different languages that both drives and is driven by social and cultural change. In accordance with the Irish constitution, Irish-English bilingualism is visible on city signage; English is the dominant language of city life and, at the same time, the global lingua franca that claims speakers from a range of backgrounds; and inward migration has led to the dramatic linguistic and cultural diversification of the city as a whole.

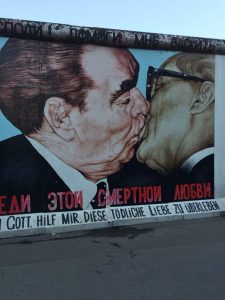

During my first weekend in Dublin, I decided to visit temple bar street and bars in order to get the complete tourist experience. Furthermore, when I visited the local pubs after, I was able to draw various contrasts between the linguistic landscape of both the places. In temple bar, English was the commonly spoken language, with menus, conversations and announcements in this language. The songs that were played were also dominantly English and the categories of alcohol served were mainstream brands that I recognised. However, in the local pubs, there was a heavy influx of Irish language and culture. It was filled up with locals who were catching up on drinks after work with Irish live music and the local stepdance being a consistent factor in all. This showed me how music helps them preserve this culture and pass it down across the generations. The alcohol in these pubs were smaller, locally produced brands that were comparably cheaper in prices. Thus, one can see how “the symbolic functions of language help to shape geographical spaces into social spaces.” (Leeman and Modan, 336)

Dublin is very well connected through it’s public transport networks. Dublin’s light rail transit system, the Luas, displays and announces all stops bilingually in English and Irish. Dublin Bus serves the city and greater metropolitan area; destinations are usually displayed bilingually (English/Irish) on the front of the bus. As a service, however, Dublin Bus functions in English and its website is available in English only. When I arrived at Dublin airport, I easily got the impression that I have arrived in a bilingual country. However, outside of the public and educational spheres, Irish is not as audible as public signage suggests. The Irish language has a protected status in the public sphere due to its constitutional recognition as “first official language” of the Republic of Ireland. This legislation explains the visual prominence of the Irish language in Dublin in the civic sphere. The language spoken in Dublin is English. Street signs and official buildings are signposted in both English and Gaelic, the indigenous Irish language. Despite this, I have not heard much Gaelic spoken on my travels across town. I have, however, come across a lot of cursing in casual conversations.

There are examples of pragmatic multilingualism outside of the Irish/English paradigm. Road rules are available in Irish, English, Russian, Polish and Mandarin Chinese. Migrant languages are very visible in the shop-fronts of Dublin’s cityscape, and are arguably the languages most encountered in the city’s streets by citizens and visitors alike.

The city of Dublin has a long history of societal multilingualism. Our brief exploration of multilingualism points to some of the power relations and tensions in a city which is impacted by an official bilingual language policy, recent migration, international tourism, industry and a globalised economy. Perhaps conceiving of Dublin as an ethnoscape, with all the complexities and changes inherent in human and urban life, is an interesting way of understanding multilingual lives in the city.

9

9