San Francisco is a bustling city filled with people from all parts of the world. San Francisco boasts the largest Chinatown outside of Asia. In a 2009-2013 census, 40.4% of the participants said they spoke a language different from English at home. The people of San Francisco are bringing the languages around the world to this city, however the government officials ruling this city are slow to adapt to the residents of this city. In a city with so many different cultures melting into a small 46.89 square miles, San Francisco’s population is incredibly multilingual, however the official signage on streets, maps, public transit ways, and government-regulated signs remain in English.

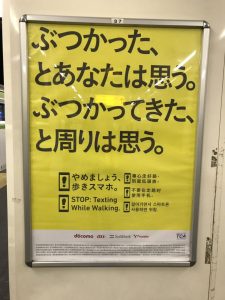

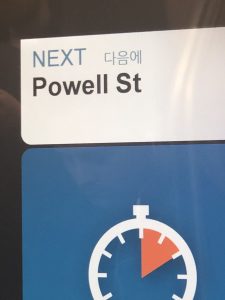

The BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) connects most of the Bay area from Oakland to Berkeley to Richmond and of course San Francisco. On one given weekday, January 19 of 2019 for example, there were approximately 395,860 riders alone. Aside from the BART, public transportation in San Francisco is widely used and well connected with over 21 different public transportation services available. I have ridden public transportation everyday for the past month and only have ridden the new BART trains once out of an approximate 65 rides. These new trains have automated screens displaying the upcoming station, the word “next” has smaller translations in 4 different languages, Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Spanish. Interestingly the top 4 languages spoken other than English in a census from 2009-2013, are Spanish, Chinese, Tagalog, and Vietnamese. While these new screens are a step in the right direction towards a multilingual city, they aren’t fully implemented on the subway system, on all types of public transportation, nor translate any important information such as stop names or directions. Aside from these baby steps, I wasn’t able to find any variation in language in any government-issued signs.

Korean label on BART train

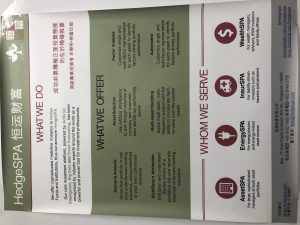

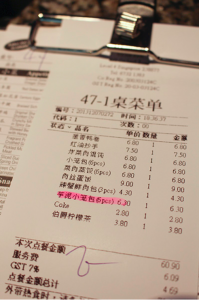

The residents of San Francisco recognize the multilingual landscape and that’s why businesses and restaurants often have different languages on signs. The Missions District is a prominent Spanish-speaking area. When I was in the Missions District, I noticed a Chinese butcher shop and was intrigued because I assumed that most of the surrounding area couldn’t read Chinese. When I entered I noticed that aside from the meat, all the side products such as condiments or prepared foods were Chinese or Mexican companies. On the signs for the meat itself, underneath the English label there were Spanish labels. I noticed that a customer and an employee of the establishment were having an interaction entirely in Spanish. I spoke to the employees in Mandarin. This shop, like many others around this city, remained true to their identity as a Chinese-owned establishment, yet adapted to the environment they were in and realized that they needed to use Spanish to attract the consumers of the area. The placement of English on the signs served as universal baseline to guarantee that no matter what language you natively speak, there was a way to convey the information needed. English was used not because it reflected the linguistic landscape of the Missions District, not because the owners of the establishment use it, but because it is the official language of the country.

Leeman and Modan identify political, social, economic factors to makeup the linguistic landscape of a city. While San Francisco’s political powers haven’t recognized the multilingual landscape, the social and economic powers of the people and business owners have and have changed the signs as well as the use of spoken language to reflect that.

Works Cited

“GCT-PH1 – Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 – County – Census Tract”. 2010 United States Census Summary File 1. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

Leeman, J & Modan, G. (2009), Commodified language in Chinatown: a contextualized

approach to a linguistic landscape. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 13(3), 332-362.

“Ridership Reports.” Bay Area Rapid Transit, www.bart.gov/about/reports/ridership.

US Census Bureau. “Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English.” Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English, 28 Oct. 2015, www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html.