The unique ethnic and multilingual nature in Singapore is fascinating yet sometimes perplexing. It is more culturally diverse than I had remembered and imagined; somehow everyone, including local Singaporeans, temporary expatriates, as well as immigrants from neighboring Asian countries, are able to make up this rather peaceful, tiny, multilingual country. Despite this “melting pot”, the two most spoken languages, English and Mandarin, brings most groups together. Among the 96.8% of literate residents, 73.2% of them are literate in at least two languages in 2015 (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2015). This statistic is reflected in my workplace as well; from casual conversations, I discovered that all of my co-workers are conversational fluent in least two languages, with many knowing three or more. Even though Singapore is located in Asia, English remains the top spoken language at home, with Mandarin, other Chinese dialects, and Malay trailing behind. Therefore, as Singapore continues to accelerate into an important business hub pushed by the “globalization of English” (Leeman and Modan 2009), linguistic landscapes in the country have certainly adapted to this development.

Based on personal observations and experiences, I realized the languages I am exposed to is very much dependent on the people I choose to associate myself with and where I travel in the city. For example, I communicate with all of my co-workers in the office using exclusively English, while I may choose to speak Mandarin ordering food in a Chinatown hawker center or at a food court in a mall. Luckily thus far, everyone who I have spoken to could understand at least one of the two languages.

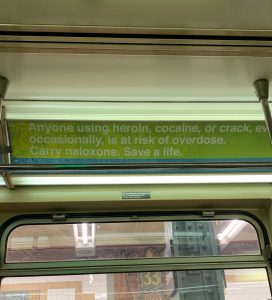

Corporate development in Singapore draws several parallels with that in American Chinatowns. Recent changes “with Chinese text less visually prominent”, as well as “English, and not Chinese, bear[ing] the functional load of ideational communication” are also reflected in written words around Singapore (Leeman and Modan, 2009), evident from the signs located across the city and specifically in the MRT stations. The majority of signs, directions, and names feature only English or English and Mandarin. However, I have noticed a few signs in the subway stations that are translated into four languages, including English, Mandarin, Malay, and Tamil. I never understood the full reason behind this, but speculate it is because English is the most used language in the country; whether you’re from an Asian or western culture, most people can understand and read the basics of English (unlike some of the other Asian languages). Additionally, the signs featuring only one or two languages are normally ones that are more straightforward to understand; many times, there are symbols such as a single letter or colors to further indicate the message of the sign for individuals who may not be as fluent in the language.

Unlike DC’s Chinatown in the early days where they wanted to “preserve and promote the neighborhood’s Chinese status” (Leeman and Modan, 2009), I find Singapore having less of an urge to do the same. The Republic of Singapore, which was established after they gained independence back in 1965 (History of Singapore, 2019), is still very young. Nevertheless, the country has already become an international hub, making it difficult for the government to keep their own dialect in the linguistic landscape and to preserve the original culture. Despite the mixture of nationalities, most local Singaporeans still speak some form of Singlish, a colloquial Singaporean English and something unique to this country. Thus far, I have only encountered a handful of individuals who have had a very strong Singlish accent, making it difficult to understand. But for the most part, the Singlish I have heard is still very similar to standard English, since English is one of Singapore’s official languages and its use is encouraged by the government (Singlish, 2019).

Singapore’s linguistic landscape continues to amaze me every day. Discovering new aspects of its culture and people through the small interactions and observations provides a new lens to certain encounters. As I head on to the second half of my time here in Singapore, I hope to converse with locals, building towards a more well-rounded experience.

Nevertheless, within specific ethic neighborhoods, such as Chinatown, Little India, and Kampong Glam, smaller street signs only present information in English and the one corresponding mother-tongue of that area, so Mandarin, Tamil, and Malay respectively. An example of this can be seen below in my photo of a Telok Ayer Street sign. Telok Ayer is a street located in Singapore’s Chinatown, and so consequently, the languages used on this sign are English and Mandarin.

Nevertheless, within specific ethic neighborhoods, such as Chinatown, Little India, and Kampong Glam, smaller street signs only present information in English and the one corresponding mother-tongue of that area, so Mandarin, Tamil, and Malay respectively. An example of this can be seen below in my photo of a Telok Ayer Street sign. Telok Ayer is a street located in Singapore’s Chinatown, and so consequently, the languages used on this sign are English and Mandarin.