Cynthia Martucci

On Thursday, our class paid a visit to the Cimetiere du Pere Lachaise, a famous cemetery in Paris where many prominent figures are buried. What initially struck me was the intricacies of the burial structures, some complete with doors and stained glass. I listened to Rick Steves’ audio guide of the cemetery as I wandered through the cobblestone streets. On one track, I noticed a familiar song- The Minute Waltz, by Frédéric Chopin. It was a piece I had learned to play when I was a kid. Next thing I knew, I was standing in front of Chopin’s flower-adorned grave. Chopin had often been coined as a child prodigy. This led me to wonder whether his brain had structural differences from other non-musicians buried nearby, and if so, whether these differences were a product of nature or of nurture.

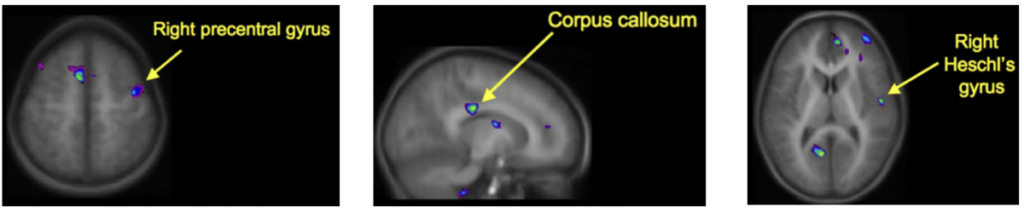

A study by Hyde et al. from 2009, titled “Musical Training Shapes Structural Brain Development”, investigates training-induced brain plasticity. It has been previously reported that adult musician brains have both structural and functional differences in musically relevant brain regions, such as auditory, sensorimotor, and multimodal integration areas, when compared to nonmusican adults. However, this study uniquely tries to answer whether there is a relationship between structural and behavioral changes in the developing brain, elucidating if structural differences in adults is a biological predisposition or a product of training at an early age. They conducted a longitudinal investigation of instrumental music training in children around age 6. Through behavioral tests and MRI scanning, the researchers found that regional structural brain plasticity only occurred in the developing brain of the instrument-training children. Before training, there were no significant differences in brain or behavior between the instrumental and control groups. By the end of the 15 months, the instrument group demonstrated significant gain in relative voxel size of the primary motor and auditory areas, and corpus callous. These were all correlated positively with behavioral improvements on motor and auditory-musical tests. This provides strong evidence that such development is induced by instrumental practice rather than pre-existing biological precursors of music ability.

I have become interested in exploring intervention methods, such as music training, that could facilitate neuroplasticity in children with developmental disorders. Neuroplasticity is something I have not been able to explore much in other NBB courses, and thus was excited to read more about it. Having grown up practicing piano, I was curious if and how this helped shape my brain. Maybe my and Chopin’s brains are not that structurally different after all 😉

Reference:

Hyde, K. L., Lerch, J., Norton, A., Forgeard, M., Winner, E., Evans, A. C., & Schlaug, G. (2009). Musical training shapes structural brain development. Journal of Neuroscience, 29(10), 3019-3025.

Interesting! I worked in a Tourette’s syndrome and ADHD lab that used transcranial magnetic stimulation to look at motor inhibition responses in children, and we observed, though did not officially measure, that children who played musical instruments had much more mature motor cortex responses compared to children who did not.