The rapidity at which the field of neurosurgery has continued to evolve became evident to me during this week’s visit to Musee d’Histoire de la Medicine (Museum of the History of Medicine). We began the tour by observing what, at first, seemed to be ancient hunting tools from the San people of Southern Africa. They were mismatched in size, had asymmetrical designs, and had a mix of smooth and jagged edges. I soon found out that I was staring at the first neurosurgical toolkit used by an early French neurosurgeon. It amazed me at how these rudimentary tools were used to penetrate and tinker with an organ as complex and delicate as the human brain. Even more incredible was how these tools served as the foundation for numerous generations worth of advances in neurosurgical equipment. As we progressed down the glass boxes encasing the toolkits, I noticed them to start to garner a more sophisticated form. They became increasingly symmetrical and gradually adopted a more streamlined appearance. Interestingly, I noticed how aesthetics became more of a priority. Near the beginning of the tour, prosthetic limbs had the appearance of a robotic arm. However, closer to the 19th and 20th century, the prosthetic limb, once decked out in rusted metal, was replaced with a pale tone and easily distinguishable fingers.

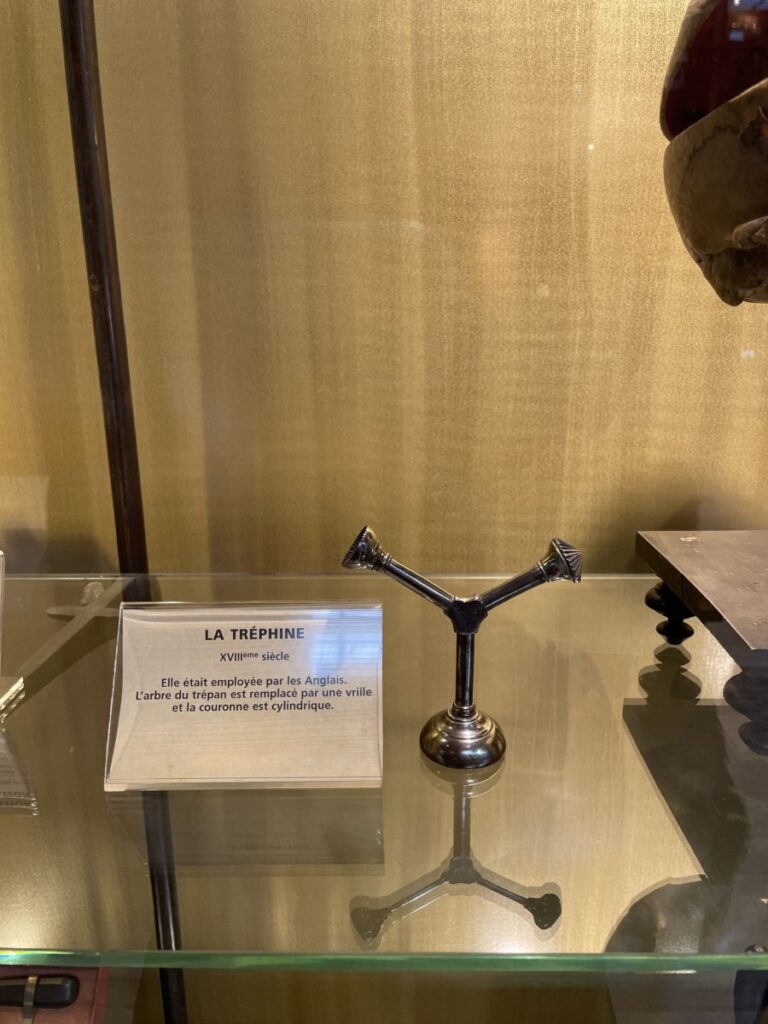

Later in the tour, I stumbled across a tool called “La Trephine” meaning “The Trepan”. In medical practice, a trepan is used to create a hole in the skull in order to expose different parts of the brain for operation. Nowadays, with more advanced technology being accessible, a cranial drill is used and is often battery-powered. The trepan in the museum, however, did not look like modern day cranial drills. It was shaped like a “Y” and had a cylindrical bottom where it attached to the brain. In order to use this tool, the surgeon would grab the top parts and twist repeatedly to make circular incisions into the skull until the bone could be removed. I discovered that this tool was commonly used to treat individuals with epilepsy. Past neuroscientists thought that mental disorders could be treated by creating an opening in the skull to allow for the demons to escape. Today, we know that epilepsy is treated with anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) that decrease membrane excitability by interacting with neurotransmitter receptors and ion channels (Macdonald et al., 1995). This visit was very exciting and allowed me to develop a newfound understanding and appreciation for how far medicine has truly come.

Reference:

Macdonald, R. L., & Kelly, K. M. (1995). Antiepileptic drug mechanisms of action. Epilepsia, 36(s2). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb05996.x