This is the fourth of a series of blog posts to highlight the Libraries’ efforts to build more inclusive and diverse collections, from reflecting under-represented groups and marginalized populations to acquiring more unique material from smaller publishers, to better representing our communities and their interests.

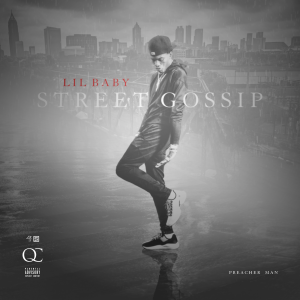

Atlanta rapper Lil Baby on his 2019 album cover for Street Gossip (Preacher Man) with Atlanta skyline

In 2017, hip hop officially became the most commercially successful genre of music in the U.S. Some people have argued that hip hop became the most popular music in the U.S. long before it topped the charts, because it has traditionally been distributed in ways that were unmeasured by the music industry, often for free. But whatever hip hop’s national popularity status, it has long been an important part of Black culture in the U.S., and especially in Atlanta. When OutKast’s André 3000 said “the South’s got something to say” in 1995, he was making a case that there were other centers for hip hop music creation outside of New York and California, and Atlanta was one of them. OutKast, the Goodie Mob, and others creatives laid the groundwork for a vibrant scene in Atlanta and across the South, which continues today.

Academics are delving into the story and influence of Southern and Atlanta hip hop. For example, the beginnings of Atlanta hip hop culture was the topic of a February 2019 James Weldon Johnson Institute lecture at Emory titled “OutKast and the Rise of the Hip Hop South” by Kennesaw State professor Dr. Regina Bradley. And Dr. Bradley was not speaking to empty room—the lecture was so popular, they were turning people away even before it started; luckily, you can watch it here. Shortly after this lecture, Dr. Bradley’s podcast series Bottom of the Map debuted, taking on a variety of topics like the creation of trap music by Jeezy, T.I., and Gucci Mane and the industry-disrupting “Old Town Road” of another Atlanta artist, Lil Nas X. She recently published a book on the topic: Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip Hop South (University of North Carolina Press, 2021). Another notable chronicle is Dirty South: OutKast, Lil Wayne, Soulja Boy, and Southern Rappers Who Reinvented Hip Hop by Ben Westhoff (Chicago Review Press, 2011). Emory has also prioritized hip hip culture scholarship—just a few months after Dr. Bradley’s OutKast lecture, Emory hired its first hip hop professor, Dr. Alix Chapman, who started at Emory in Fall 2019 and regularly offers a class on Black Music. And in Fall 2021, the Emory Music Department is offering its first course on hip hop sound production, led by DJ Rasta Root (MUS 270, section 2).

Despite hip hop’s prominence and important societal impact in Atlanta, after joining the Emory Libraries team in 2016 and digging into local collecting practices, I realized that while several of the local public libraries had good (if spotty) Atlanta hip hop and R&B audio collections, none of the other universities in Atlanta (including Emory) were trying to comprehensively collect the hip hop/R&B albums by Atlanta-area artists. I set out to change that, having conversations with hip hop experts such as Black Emory students and faculty, creating lists, delving through discographies, looking at record reviews (for example, Black Grooves), reviewing popular music magazines, and paying attention to Atlanta billboards and other public advertising. While I have been moderately successful in collecting albums, identifying 74 Atlanta hip hop acts and buying around 200 Atlanta hip hop and R&B albums (both in CD and vinyl form), I have been stymied by the digital trends of music—many artists, especially new artists and hip hop artists, do not release their albums physically, but only via streaming services. This is not too surprising, since digital distribution is easier (especially for marginalized communities) and growing ever more popular (digital music sales have made more money than physical sales since 2011). I have identified hundreds of albums by Atlanta hip hop artists where a) physical copies are not longer available for purchase or b) the albums did not have a physical release of any type. Streaming services usually feature End-User License Agreements (EULAs) that prohibit libraries from purchasing streaming versions that we can check out to our users.

Atlanta rapper Yung Baby Tate’s 2019 album Girls was only released digitally—libraries can’t collect it

You might be asking—why does it matter if libraries collect items in physical form, when everyone has access to the sounds recordings through YouTube or Spotify? Here are my answers:

- Record companies have a history of ignoring or dropping parts of their recording catalog that they perceive as not popular or not making money, which can have greater effect for traditionally marginalized groups such as Black people.

- Even if companies don’t purposefully lose content, sometimes they do it by accident—remember MySpace losing 50 million songs?

- Not just the content, but sometimes entire tech companies have a history of disappearing overnight, even very popular services. Did you know that despite controlling (a diminishing) 36% of the streaming market, Spotify still does not consistently make a profit?

- The streaming version of an album often has very little information about the music, also called metadata. Detailed information such as who created the tracks, who performed, the lyrics, and the album artwork is important for research and is usually available on the physical version.

Atlanta hip hop is not getting any less popular or less culturally important. For example, I passed the Atlanta Trap Museum on a Saturday afternoon in late March 2021, and even in pandemic conditions the line to get in was several blocks long. This for a venue originally meant as a pop-up project. I plan to continue collecting sounds recordings in this area, both buying physical recordings when available, and attempting to solve the problems presented to libraries by digital production, so that this local/national music scene can be preserved for the future.

—by Peter Shirts, music librarian, Heilbrun Music & Media Library, Robert W. Woodruff Library