By Courtney Chartier, Assistant Head, Archives Research Center, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library

“Working for Freedom: Documenting Civil Rights Organizations” is a collaborative project between Emory University’s Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, The Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History, The Amistad Research Center at Tulane University, and The Robert W. Woodruff Library of Atlanta University Center to uncover and make available previously hidden collections documenting the Civil Rights Movement in Atlanta and New Orleans. The project is administered by the Council on Library and Information Resources with funds from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Each organization regularly contributes blog posts about their progress.

“Working for Freedom: Documenting Civil Rights Organizations” is a collaborative project between Emory University’s Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, The Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History, The Amistad Research Center at Tulane University, and The Robert W. Woodruff Library of Atlanta University Center to uncover and make available previously hidden collections documenting the Civil Rights Movement in Atlanta and New Orleans. The project is administered by the Council on Library and Information Resources with funds from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Each organization regularly contributes blog posts about their progress.

For more information about the collection described in this post, please contact the Archives Research Center at Atlanta University Center, archives [at] auctr [dot] edu

Become involved in the movement when he organized the first student sit-in in Nashville, where he was a student at the Baptist Theological Seminary and then Fisk University. He was involved in the first CORE sponsored Freedom Ride in 1961.

Lewis was elected Chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in 1963. While Chairman he orchestrated SNCC’s Mississippi Freedom Summer (1964) and spoke for the organization at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (1965).

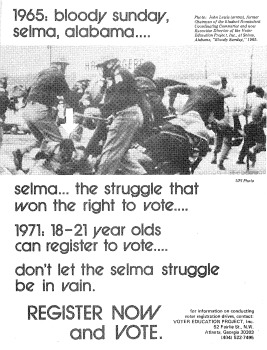

In 1965 Lewis was one of the organizers of the Selma to Montgomery March. The first attempt at marching ended in a violent confrontation on the Edmund Pettius Bridge between marchers and local and state police, that would come to be known as “Bloody Sunday.” The nonviolent demonstrators were beaten, gassed and driven back into Selma. Sherriff Jim Clark and his men attacked marchers on horseback with cattle prods and clubs. Lewis was one of the casualties of the conflict; his skull was fractured.

Demonstrations in Selma were covered in the national news due to the violence on the Pettus Bridge, as well as the murder of Violet Liuzzo, a white volunteer from Detroit, by local Klu Klux Klan members. The march was successfully completed only after a court order, and widespread horrified reactions to the coverage of the violent conflict is credited with speeding up the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

(Click image to see a larger version.)

Lewis’ dedication to nonviolence was complete (nicknamed “Mr. Endurance”), and he was the first African-American registered as a conscientious objector to the war in Vietnam. His philosophies led to problems with more militant leaders within SNCC, and he was ousted in 1966 by Stokley Carmicheal. Afterwards he worked as both an Associate Director of the Ford Foundation and Director of the Atlanta Community Organization Project of the Southern Regional Council. He took a leave of absence from SRC to work on the Robert F. Kennedy campaign, and was with Kennedy when he was assassinated.

Lewis replaced Vernon Jordan (who left to head the United Negro College Fund), as Executive Director of VEP in 1970. His immediate focus was on fundraising, the continued distribution of funds, and weaning the organization away from Southern Regional Council. Lewis served VEP until 1977, when he ran unsuccessfully for a Senate seat. He was then elected to the Atlanta City Council. Lewis has been a member of the U.S. House of Representatives representing Georgia’s 5th Congressional district since 1986.

On March 7, 1975 Lewis, Julian Bond and Coretta Scott King organized and led a return to Selma to commemorate the ten year anniversary of the march. The event began with speeches at the Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church, followed by a march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Lewis returned to a much changed Selma. Not only was Sherriff Jim Clark gone from office, but by 1975 seventy percent of Selma’s African-American population (approximately fifty percent of the overall population) was registered to vote. In 1965, only 2.1 percent were registered, even though the population percentage was similar. Half of the 10 members of the 1975 Selma City Council were African-American, while in 1965 there was no city official of any rank that wasn’t white.

The second march was more than just a commemoration of an essential event in the Civil Rights Movement. The 1965 Voting Rights Act only had a ten year life, and as Executive Director of the Voter Education Project, John Lewis was set to testify before Congress in favor of an extension. The second march, although taking place in a changed Selma, was a dramatization of the work still left to be done in the South.

Lewis said, “We cannot become apathetic. We must not take our freedoms for granted for there are many who paid a high price so that we could have him.” At the march he wore the same orange vest that had marked him for over forty arrests in his time as a student leader.

On February 15, 2011, Congressman John Lewis received the 2010 Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama.