It’s quite easy to type a few keywords into a library search engine and forget that there is a human (actually, many humans) working behind the scenes and contributing to the results you see. Scrolling through a library catalog, like Emory’s Library Search, everything seems polished and objective.

Interestingly, library catalogs have long been a site of conflict over what Hope Olson refers to as “the power to name” (The Power to Name: Locating the Limits of Subject Representation in Libraries). How should librarians describe books, articles, and media to make them findable when researchers look for them? What is the most helpful language to use for a concept, idea, or even a group of people to enhance search results?

When librarians make decisions about the best keywords to apply to the catalog, we are exercising our power to name materials and directly impacting the research process. As a field, we have always wrestled with (and often fiercely debated) how to hold this responsibility in the least harmful and most helpful way for library users.

Harmful Language Project

In April 2024, Emory Libraries announced its intention to take a critical look at our library catalog, acknowledging that subject headings used to describe library materials—particularly materials about historically (and contemporarily) oppressed peoples—contained outdated, harmful, and/or offensive terms. While our motivation in creating a Harmful Language Project was primarily ethical, we also hoped to adopt more accurate language that would improve the findability of our materials.

Because Emory is striving to offer inclusive and non-derogatory information in the library catalog, we developed a working solution to mask or altogether replace problematic subject headings. Our replacement terms were selected carefully and deliberately, informed by recommendations from library advocacy groups who are interested in improving inclusive language in library catalogs. We also conducted a survey of the Emory community to get your feedback on the changes we proposed.

Inclusive Language in Practice

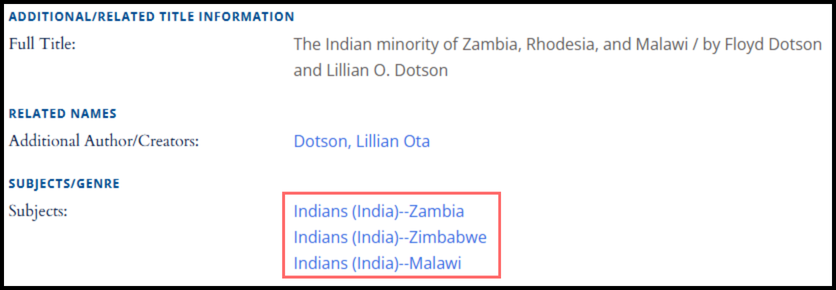

As an example, we worked in consultation with the South Asian SACO Funnel, which advocates for better representation of South Asian people and topics in subject headings, to adopt the term “Indians (India)” to describe books, articles, and media about the inhabitants of India. This new term ultimately replaced our former heading of “East Indians.”

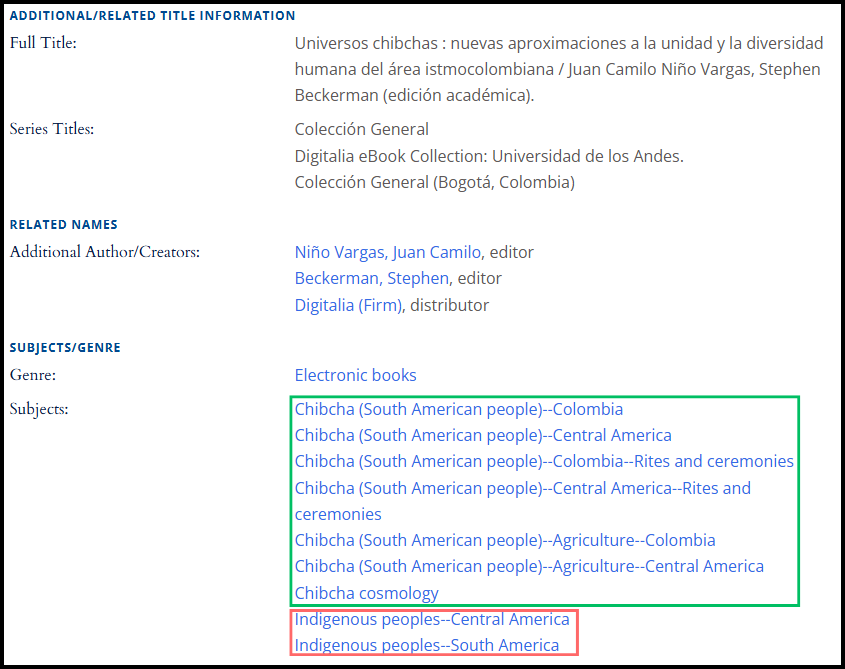

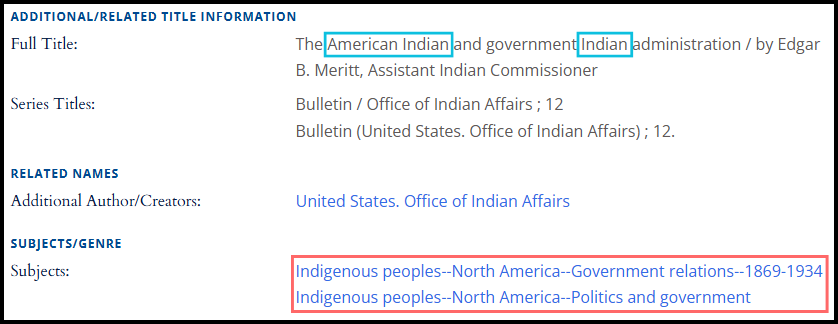

While our catalog previously used the term “Indians of North America” and “Indians of South America” to describe the indigenous peoples of the Americas, we acknowledge that this is misleading terminology based in historic and ongoing realities of colonization. Therefore, we decided to replace all instances of “Indians” with variations on “Indigenous peoples” and/or “First Nations” to more accurately describe these experiences. We also worked in collaboration with Backstage Library Works to adopt the preferred terminology of Indigenous and First Nations groups, wherever possible.

Other groups and resources we consulted included the African American SACO Funnel, Homosaurus (an international vocabulary created by the LGBTQ+ community to describe LGBTQ+ resources), and the Triangle Research Libraries Project (an initiative for revising harmful language in library catalogs). This research guided our decisions to replace language throughout Emory’s catalog, and you can review the full list of changes here.

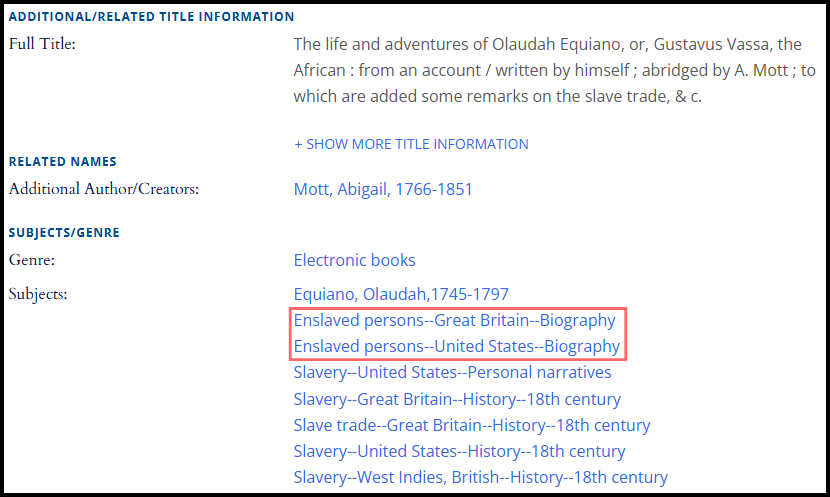

To demonstrate inclusive language in practice, subject headings such as “Rural sexual minorities” changed to “Rural LGBTQ+ people” to improve the research process and prioritize terms researchers are likely to use. In addition, terms like “Illegal aliens in literature” and “Hearing impaired children” became “Noncitizens in literature” and “Hard of hearing children,” respectively. These changes reflect the language preferred by representative community advocacy groups. Similarly, the term “Slaves” has been replaced with “Enslaved persons” to underline both the humanity of, and action being forced upon, those represented.

A Work in Progress

While the new subject headings implemented by Emory Libraries’ Harmful Language Project are currently live in the catalog, we want to emphasize that adopting inclusive and non-derogatory terminology is an ongoing, reiterative, and messy process. For example, while “Indigenous peoples” may be the subject heading assigned to a book, the resource’s title will remain transcribed and retain the phrase “Indian,” if it was used.

Moreover, after surveying library users, we acknowledge that this project has received a fair amount of support as well as criticism. Taking feedback into deep consideration, we have made several adjustments to our rationales and goals. For example, one survey participant suggested that an additional area of focus could be outdated disability language with regards to neurodiversity. This suggestion fits well within the scope of our intentions for reducing harmful language in the Emory catalog and will be considered for future projects.

On the other hand, it was also suggested that the “people-first” language informing our revised subject headings should apply to terms such as “Enslavers,” resulting in terms like “Slave-owning person.” Our rationale for deciding against such phrasing is that our people-first approach is intended to revise language associated with identities. For example, “Gay people” is preferred over “Gays” because the latter focuses more on the label than the person, which can feel dehumanizing. In contrast, terms such as “Enslavers” are about actions and the responsibility of accurately attributing those actions to their actors. In addition, the term “Enslavers” may refer to larger bodies and systems, rather than just individuals.

Finally, what we hope this reflection makes clear is that there is no universal agreement on how to make library catalogs less harmful and more inclusive. While our actions are well-intended, this initiative has by no means solved the underlying problems and biases that warranted a Harmful Language Project in the first place. Nevertheless, we do hope that this project represents a small step forward in improving the Emory Libraries catalog. With that in mind, reducing harmful language will be an ongoing effort, and the replacement terminology we are using will remain open to revision.

We are open to feedback!

If you have any feedback or comments, please consider making a submission via this form. In addition, you can report anything in the catalog that seems offensive, harmful, or misrepresented.

— Jude Romines (he/they), Woodruff Library Resource Description Team