Hegel’s concept of sense-certainty in Phenomenology of Spirit reminds me of many others concepts, including experience and embodied cognition (psychology). “Certainty as a connection is an immediate pure connection: consciousness is “I”, nothing more, a pure “This” (91), Hegel emphasizes the importance of direct connection to something in order to verify its own truth. For experience, we are sure that we see what actually happens. In Hegel’s terminology, we sense this “Now”, and our “I” confirm that the truth is “Here”. Beside experience, embodied cognition somewhat illustrates Hegel’s point. Embodied cognition focuses on human behaviors and thoughts based on the environments. Let’s consider Hegel’s usage of the tree falling into the woods. The noise does not exist when there is no one around it, for we cannot certainly say that it is there without being there. One condition of hearing the truthful sound is being there in the woods. Our body has to show our mind that we hear (sense) the sound (certainty).

“But what has been, is not; I set aside the second truth, its having been, its supersession, and thereby negate the negation of the “Now”, and thus return the first assertion, that the “Now” is” (107) Does the truth change? Answer: Yes, it does. We experience and see changes every day. Our body changes in many small ways, and we can say that we are physically not the same person we were yesterday, or even a minute ago. Yet, there are many things that make up the truth of one thing as Hegel would argue. A truth is not simple, but contains many other things. For example, one person reads for five hours straight. What is the absolute truth? In this case, he tells himself that it is him cramming for his exam. His body (embodied cognition once again) assigns this intense condition as cramming for an exam. However, after the exam, he reads books for eight hours straight. Does it mean that he still studies according to his experience/embodied cognition? In a way, he does. In a way, he does not. The truth is not what it seems. Did you just read all I wrote? Are you sure that you did not imagine hearing what I just wrote?

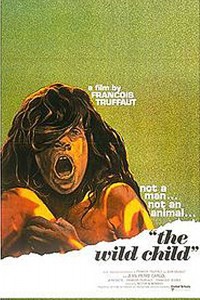

In discussions about identity, philosophers often mention the influence of others on a self. In our most recent readings about self-consciousness, Hegel says, “Self-consciousness exists in and for itself when, and by the fact that, it so exists for another; that is, it exists only in being acknowledged.” He then goes into a discussion of the interaction between two beings and how the interaction is what makes them fully self-conscious. So if this reaction never existed, what would be the result?

In discussions about identity, philosophers often mention the influence of others on a self. In our most recent readings about self-consciousness, Hegel says, “Self-consciousness exists in and for itself when, and by the fact that, it so exists for another; that is, it exists only in being acknowledged.” He then goes into a discussion of the interaction between two beings and how the interaction is what makes them fully self-conscious. So if this reaction never existed, what would be the result?