What does a business concept have to do with teaching theology?

Tom Kelly writes that a “Hands-on, user-centric approach to problem solving can lead to innovation, and innovation can lead to differentiation and competitive advantage.”

As theological educators, our work is not inclined toward competitive advantage. Our work is to be present, embodied, and full of understanding as we teach and as students learn.

This is the motivation of the first session in our “Creative Assessments Cohort” grant from the Wabash Center: Design Thinking for Pedagogy.

The Process

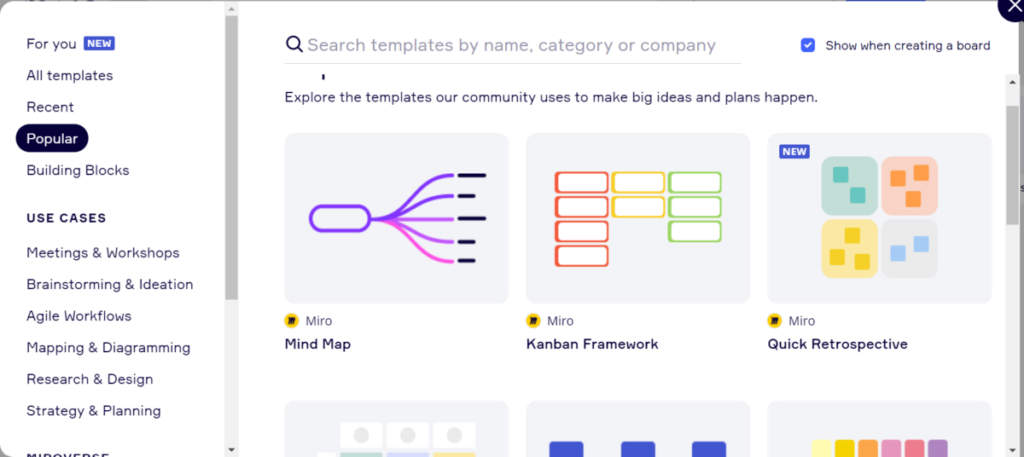

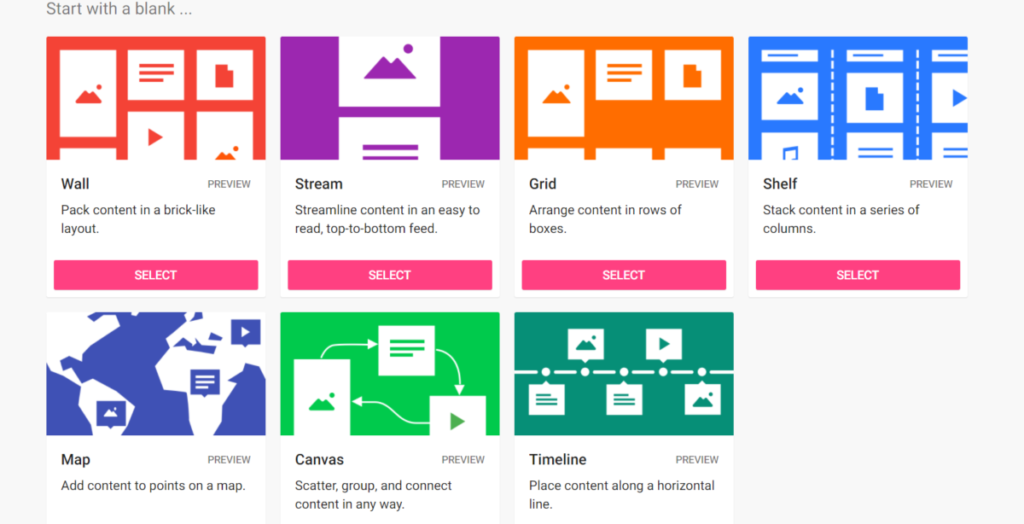

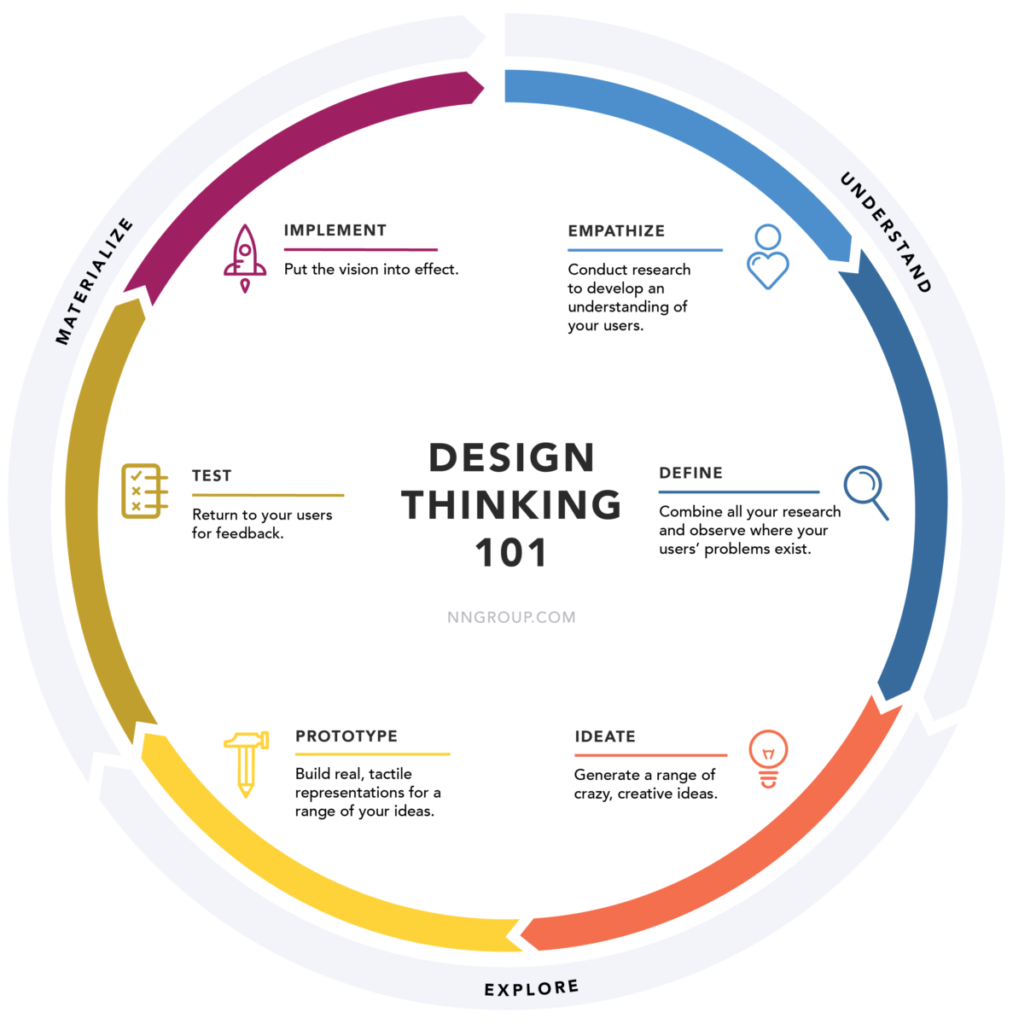

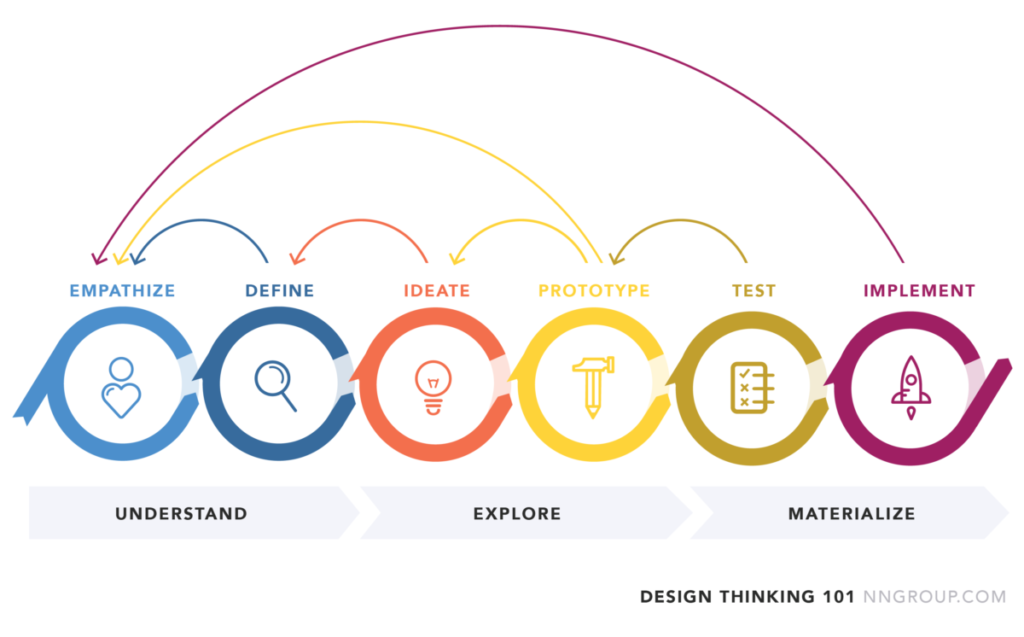

Design thinking is both a concept and a process of six different phases:

- Empathize

- Define

- Ideate

- Prototype

- Test

- Implement

Empathize

As a business approach, empathy here is rooted in conducting research to understand the consumer. It attempts to place the researcher in the mind of the consumer and explore how they might do, say, think, and feel.

Define

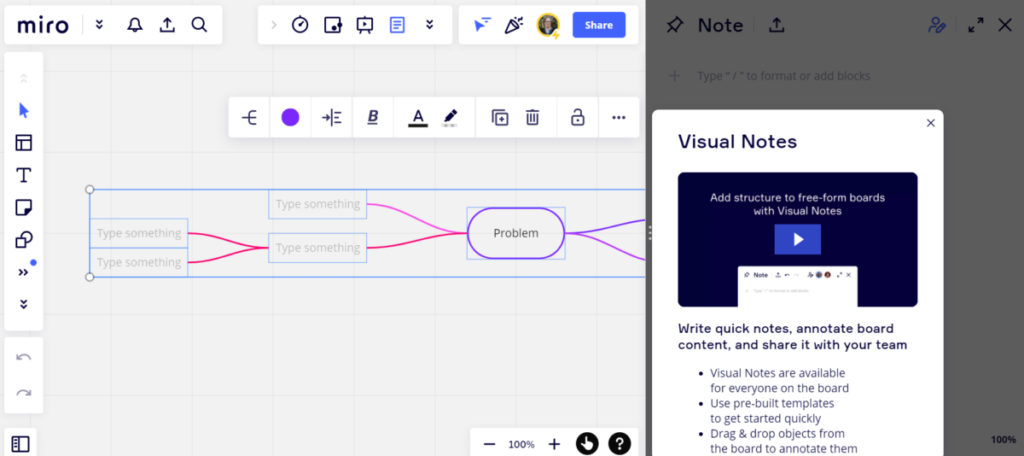

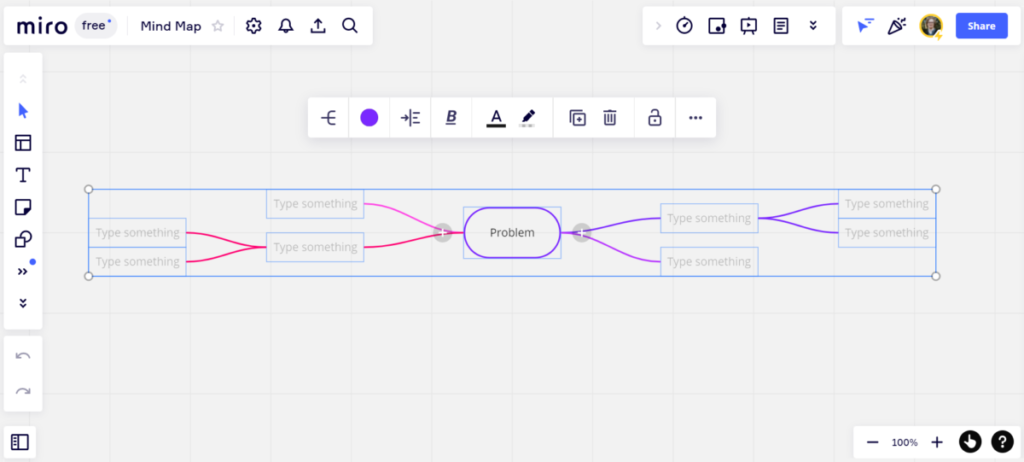

As you define, organize all of the areas that might connect the experiences of different consumers. Where are the problems?

Ideate

This is the step where there are zero limits. At this phase, you and your team can brainstorm. Throw out ideas on how to address the problem you have defined. What would it look like to solve this problem if you had no limitations on money, personnel, materials, etc.

Prototype

Prototype your ideas. Take a moment to make them real, especially if it is an idea for a product. If it is a new product, make it. If it is something online, map out a wireframe. If it is for the classroom, try it out the approach.

Test

To test, go back to the consumer for feedback. Ask, “Does this solution meet users’ needs? . . . Does it improve how they feel, think, or do their tasks?”

Implement

Implementing is bringing your vision to life. How does your solution impact the problem you’ve encountered? The work of design thinking is never done and always returns back to having empathy and understanding the consumer.

Design Thinking is empathy-driven

Bethany Stolle writes that “Design thinking is an empathy-driven, human-centered approach to addressing complex problems.”

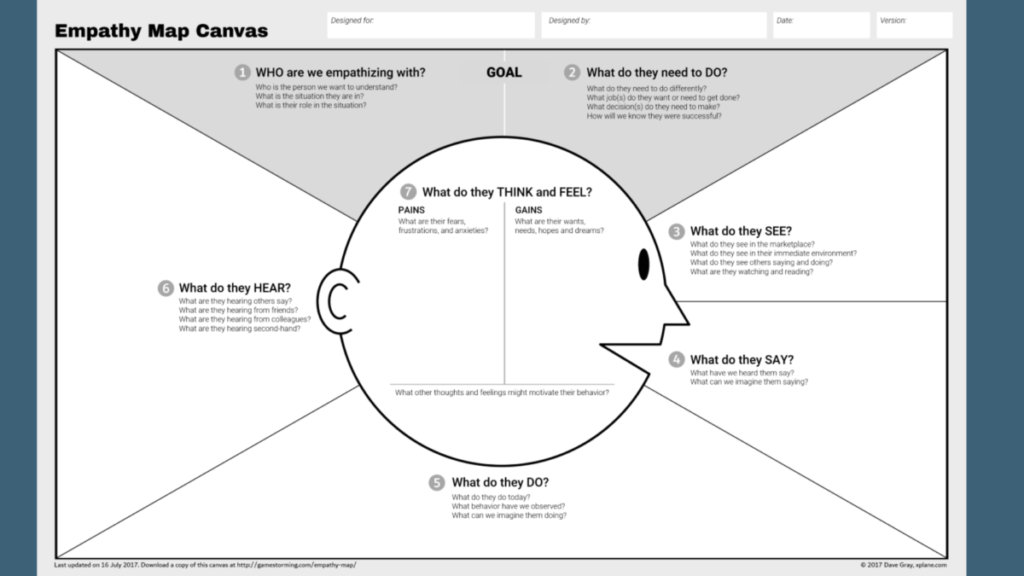

So, in design thinking, we see that every step returns to empathy. To empathize, educators must get into the minds of students. What are they going through? What do they need to do in their daily lives? What else is going on besides the few hours spent in your class?

EMPATHIZE: Try to map out all of the elements of your students’ experiences, both inside and outside of the classroom.

Once you’ve mapped your “student”, try to find opportunities to address their needs (see “define the problem”). What are your students saying? What aren’t they saying? How can you work to address these needs in your teaching?

Try out new assessments, new pedagogical approaches. Sit down with your students and ask questions rather than a traditional lecture. See how these ideas work for your students. Is there anything you can change?

Design Thinking requires continuous reflection

The strength of design thinking is in its reflection – always going back to identifying with the users, our students.

So: what does design thinking have to do with teaching theology?

Empathize. Empathize. Empathize.

We never know the extent of our students’ experiences outside of our classroom. As theological educators and faculty, it is our mission to shape faithful and creative leaders for the church and the world. By using this framework of empathy and reflection of our teaching, we can serve as models for our students and colleagues.

For more information on design thinking, check out Dr. Kathryn Common’s article here.

You can also connect with us at candlerdigitallearning [at] emory [dot] edu. We’d love to hear from you!