The team members of American Excavations Samothrace are the latest in a long succession of explorers who have investigated the ancient Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace, Greece. Emory University’s involvement reaches back to the 1980s, and since 2012 it has taken the leadership role, drawing scholars and students from the departments of Art History and Environmental Sciences, the Michael C. Carlos Museum, the Rollins School of Public Health, and the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS). This post explores reflections on the Samothrace virtual season from Michael Page (ECDS; Department of Environmental Sciences)—with additional input from Dr. Bonna Wescoat—during the COVID-19 pandemic in Summer 2020. The digital tools and methods the project team have used in adapting to new work conditions reflects a longer history of digital scholarship involved in the Samothrace project and have provided a way for project team members to collaborate and think critically about the direction of the project for the future.

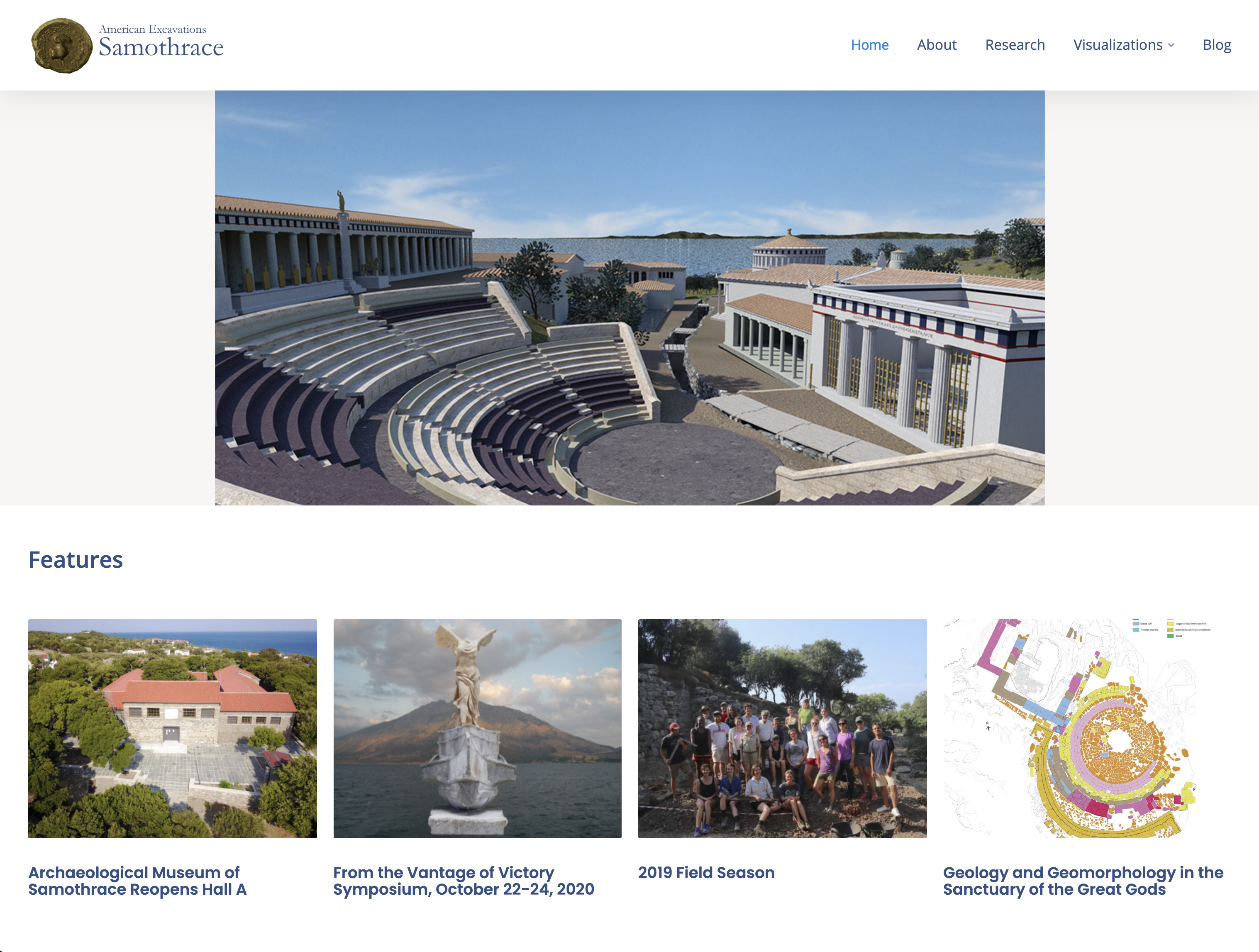

- American Excavations Samothrace: https://samothrace.emory.edu/

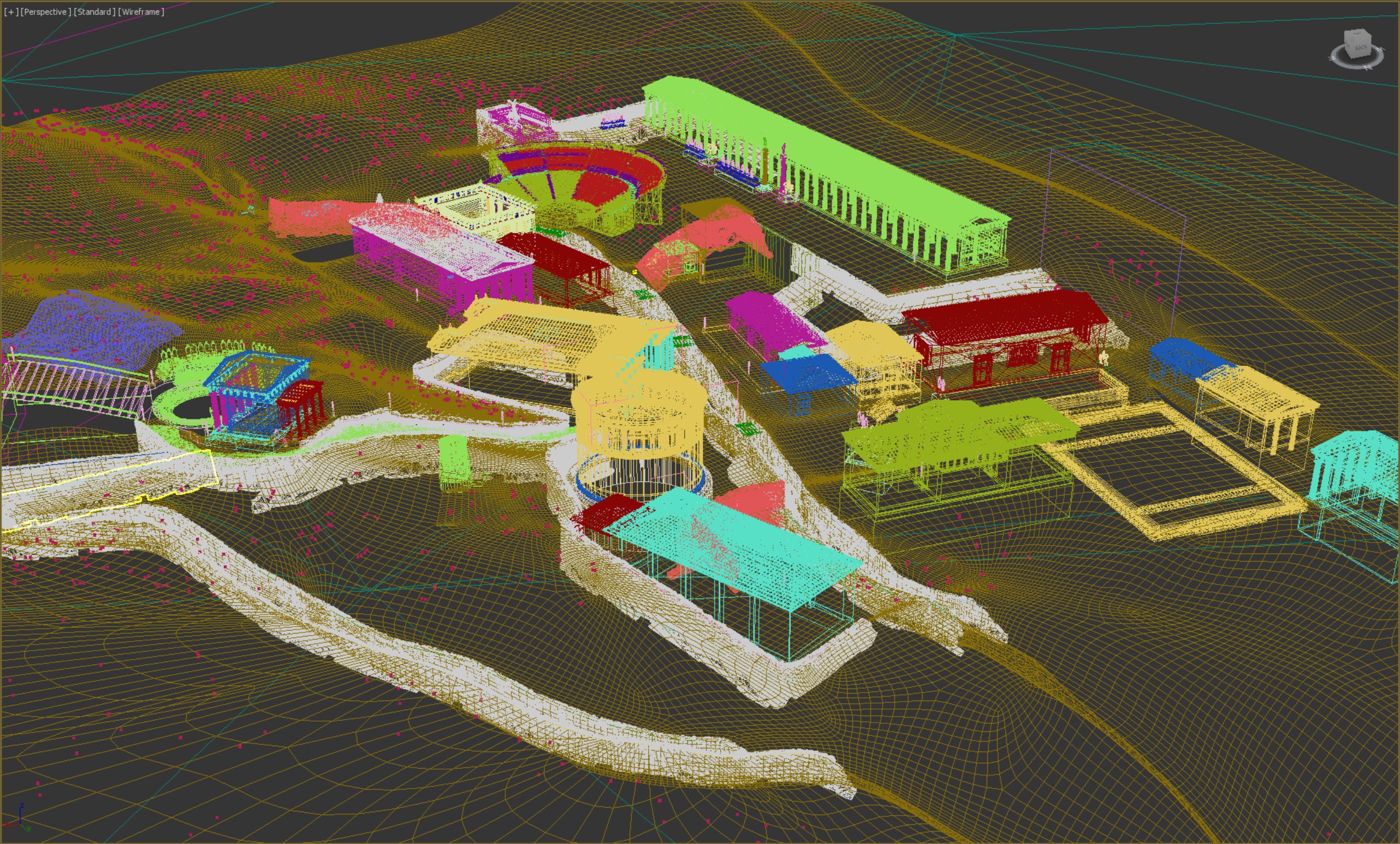

Since the 1930s, Americans have been involved in the interdisciplinary and international Samothrace project, which has included experts, staff, and students (graduate and undergraduate) from various institutions including Emory University. The American team was initially sponsored by NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts, beginning its work at the Sanctuary of the Great Gods in 1938. Alongside the NYU Institute of Fine Arts, Emory University became the lead sponsor of the research team in 2012. Every summer, teams travel to Samothrace to conduct excavations and research. Dr. Bonna D. Wescoat (Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Art History) is the current Director of American Excavations Samothrace, having taken leadership of the project in 2012. Michael Page (Geographer at ECDS) has been part of the Samothrace project for 13 years and is the director of the survey team. Other ECDS involvement includes a redesign of the website in 2015-2016, as well as work on 3D visualization of the sanctuaries conducted by team members of the Visualization Lab which include Arya Basu (Visual Information Specialist) and Ian Burr (Visual Design Specialist).

Currently, American Excavations Samothrace holds one of the three excavation permits awarded to the U.S., allowing for five years of intensive fieldwork and excavation between 2018-2022. The field season planned for 2020 was crucial, but as the pandemic continued, the project teams had to abandon plans for fieldwork and determine instead how to maintain momentum by going virtual.

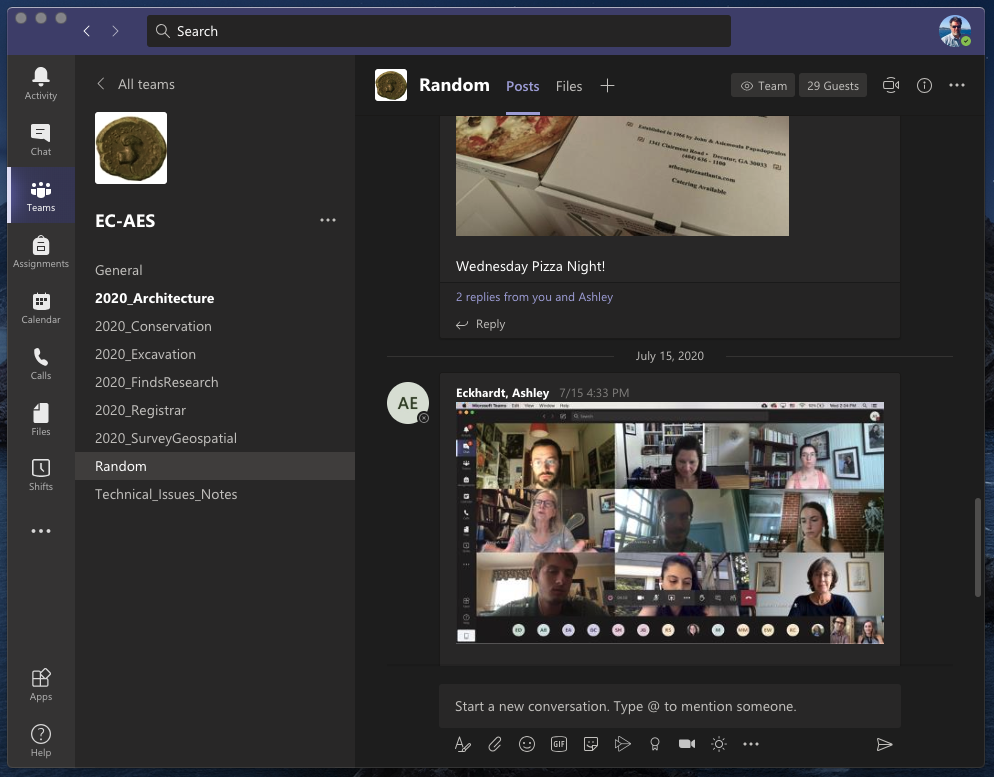

The Samothrace project is overall a physical operation, and the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted questions about how to make such an endeavor go virtual. Subteams had to find new solutions and virtual methods of maintaining work on the project. Michael Page explains that they began using Microsoft Teams to meet their goals, which included: continuing research on the architecture and finds from the region of the Stoa; completing drawings and photomodels of the 2018-2019 field seasons; planning for 2021 excavations; reformatting and renaming content for publication; and providing students with opportunities to learn/interact with the project.

Before this summer, project team members had predominantly kept in contact via email, having to link out to Box files and folders in order to share project files and data. Now using Microsoft Teams, all subteams’ channels are open and transparent, allowing for more effective communications. Rather than having to wait to hear back from a different subteam or a colleague in a different location/time zone, all information and files are available on Microsoft Teams. For example, Teams has connected colleagues from California to Greece. Even personnel who have partial involvement in the project can get a fuller scope of the work by tuning into running conversations and accessing the Files tab. The virtual environment allows everyone to “work smarter,” says Page.

Team members have also used Zoom for a regular standing meeting every Friday, allowing subteams to share their week’s work with the entire team. This practice mirrored the project’s tradition in the field. A new development was the opportunity for experts to share their research with team members through mini-lectures during the virtual “season.” While video-conferencing calls have been especially necessary for current work circumstances, adapting to such methods benefit the longer-term project. Page explains that project members plan to use Zoom in tandem with physical presence in Samothrace during 2021. “COVID-19 has made us stop and think about the way we work,” Page says. “We have had to rethink how people collaborate together, and it is interesting how things change.”

Some of those changes, like data extraction of files from Box to OneDrive, were huge enterprises. This work involved reformatting and renaming large numbers of files and confirming each transfer. Such efforts work to improve the workflow and provide many benefits for the project moving forward, including ease of access to well-organized files that are now readily available for publication purposes.

The new digital methods also reflect a longer history of digital scholarship that the project has involved. Page explains that Samothrace has been “digital” in some sense for at least 15 years, in terms of photogrammetry (gigapixel photography made possible by ECDS), 3D modeling, and more.

The 2020 Samothrace virtual season coincided with the reopening of the Archaeological Museum of Samothrace’s Hall A. Artifacts and archaeological contexts provide one of our richest resources for understanding the Sanctuary, and thus much of our work done in partnership with Greek colleagues is in service of understanding and conserving the sanctuary for present and future visitors. The museum—designed by Stuart M. Shaw (Metropolitan Museum of Art) and constructed between 1939-1961; renovated in 2014-2015—has now reopened: “Archaeological Museum of Samothrace Reopens Hall A.” The exhibition includes a video walk-through of the 3D digital reconstruction model of the Sanctuary created by Ian Burr; video available in the linked article. (See also: our previous blog post about the 3D video and museum reopening.)

To read other previous ECDS blog posts about Samothrace, including a 3D visualization video of the Sanctuary of the Great Gods (featured on National Geographic) please visit our previous blog posts:

- “Samothrace Animation Series” (August 2016)

- “Emory experts to share Samothrace cult VR secrets at CAA Conference” (March 2017)

- “Discussions on 3D Initiatives in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods, Samothrace” (April 2019)